Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

Hi there,

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

Comely Maidens Dancing at the Cross Roads - Lipstick, Powder & Politics

-

11-05-2011 5:34pm#1

Comments

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

Advertisement

Anna, photographed by Henry O'Shea, Limerick (c. 1878).

Anna, photographed by Henry O'Shea, Limerick (c. 1878).  Fanny, in ‘mid-western' costume (1878)

Fanny, in ‘mid-western' costume (1878) Their mother, Delia Tudor Stewart Parnell (1864).

Their mother, Delia Tudor Stewart Parnell (1864). Charles Stewart Parnell (Sean Sexton)

Charles Stewart Parnell (Sean Sexton)

The Royal Irish Constabulary dispersing a meeting of the Ladies' Land League. (Illustrated London News, 24 December 1881)

The Royal Irish Constabulary dispersing a meeting of the Ladies' Land League. (Illustrated London News, 24 December 1881)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3_Jvr9oAwo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3_Jvr9oAwo

© The National Archive of Ireland

© The National Archive of Ireland © The National Archive of Ireland

© The National Archive of Ireland

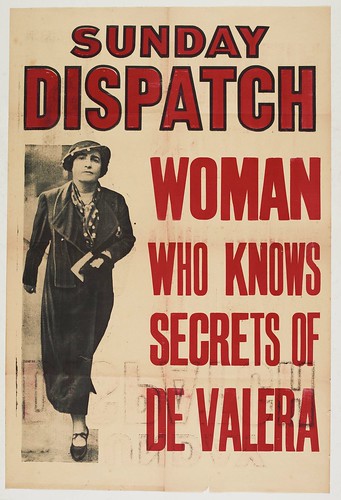

Picture of the lady herself on trial in london, 1907.

Picture of the lady herself on trial in london, 1907. a Mugshot!!!!!!

a Mugshot!!!!!! hat poem was composed by Eileen O'Leary in 1773 after her husband had been killed by a British soldier. Her husband, Art O'Leary, who was an officer in the Austrian Army, refused to sell his favorite mare to the British soldier and was shot because Catholics were not permitted by law to possess a horse of more than $:5 in value. She describes in detail her husband's beauty, his white breast, his valor, the children who do not yet know of the tragedy and how she came to know of it when the horse came back, bridle trailing, bloodied from forehead to polished saddle. She mounted it and was brought to the spot where her husband lay. Your blood in torrents Art O'Leary I did not wipe it off I drank it from my palms.

hat poem was composed by Eileen O'Leary in 1773 after her husband had been killed by a British soldier. Her husband, Art O'Leary, who was an officer in the Austrian Army, refused to sell his favorite mare to the British soldier and was shot because Catholics were not permitted by law to possess a horse of more than $:5 in value. She describes in detail her husband's beauty, his white breast, his valor, the children who do not yet know of the tragedy and how she came to know of it when the horse came back, bridle trailing, bloodied from forehead to polished saddle. She mounted it and was brought to the spot where her husband lay. Your blood in torrents Art O'Leary I did not wipe it off I drank it from my palms.

In 1930, in her capacity as secretary of the 'Friends of Soviet Russia', she travelled to Russia. On her return to Ireland she became Editor of the Republican File, a Republican Socialist journal, following the suppression of An Phoblacht and jailing of Frank Ryan. She became involved in the First National Aid Association which supported the dependents of Republican prisoners and gave continuous support to the Women’s Prisoners' Defence League. In January 1933 Hanna was jailed when she travelled to Newry, County Downspeaking on behalf of republican prisoners. She was arrested and held for 15 days in Armagh Jail as she defied an order banning from entering the Northern counties.

In 1930, in her capacity as secretary of the 'Friends of Soviet Russia', she travelled to Russia. On her return to Ireland she became Editor of the Republican File, a Republican Socialist journal, following the suppression of An Phoblacht and jailing of Frank Ryan. She became involved in the First National Aid Association which supported the dependents of Republican prisoners and gave continuous support to the Women’s Prisoners' Defence League. In January 1933 Hanna was jailed when she travelled to Newry, County Downspeaking on behalf of republican prisoners. She was arrested and held for 15 days in Armagh Jail as she defied an order banning from entering the Northern counties.