Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

Rum Sodomy & the Lash - Irish Maritime Times & Lore

Options

Comments

-

I was trying to work out where to take this thread and there are a lot of holes in our knowledge.

Riamfada the Archaelogy Mod sent me this link to an excavation of a trading vessel in Drogheda

There are some pics are here tooDay 14 – The Drogheda Boat July 22, 2010, 9:53 pm

Filed under: Uncategorized

The weather was dry on the site this morning and good progress was made in all the cuttings. After lunch the team had a treat in store for them; a visit to the Drogheda Boat. This boat dates from the 16th century and is perhaps the first archaeological excavation of a shipwreck in Ireland. Holger Schweitzer told us about the initial discovery, how each piece of timber was recorded and the model he has produced from the excavation and analysis. This work was undertaken by the Underwater Archaeology Unit of the Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government. The team got to see the remains of the actual boat and a dugout canoe recently discovered in the Boyne River.

http://bective.wordpress.com/2010/07/22/day-14-%E2%80%93-the-drogheda-boat/

The Vikings developed a lot of ports for trade etc but the Irish had boats too.

Dublin also was part of the Kingdom of the Isles for a while when under Viking control.

Anyway, here is a Map of Ireland from the 16th Century.

Before Ireland was totally under English control you had trading etc.So where were the ports and who controlled them.

The sea was also important to the Flight of the Earls - they had regular contact abroad.

In 1649 Wexford had c 40 "privateers" operating from it.

So who controlled it and what kinds of ships did they have.

Even after the English took control you had trading and smuggling.The Siege of Derry, for example, saw the Williamites funded by London Merchants -somewhat reminiscent of the East India Company.

Dont forget, customs duties were a key source of Government Revenue.

A big factor was the taxation revenue and rights to trade.

Shipping was also important for transportation and emigration.

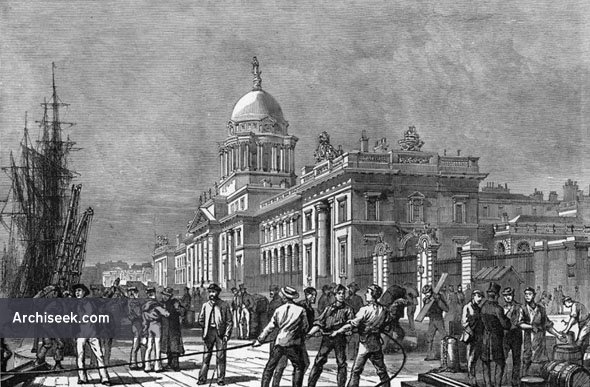

Dublins Custom House of 1791was Dublins first public building

Ireland also contributed its fair share of Naval CommandersThe Custom House is often considered architecturally the most important building in Dublin and is sited on the river front with Beresford Place to the rear. The Custom House was the first major public building built in Dublin as an isolated structure with four monumental façades. The previous Custom House by Thomas Burgh and built in 1707 was sited up river at Essex Quay and was judged as unsafe just seventy years later. The site chosen for the new Custom House met with much opposition from city merchants who feared that its move down river would lessen the value of their properties while making the property owners to the east wealthier.

The decision to built further down river was forced by the Rt. Hon. John Beresford (1738-1805) who was appointed Chief Commissioner from 1780 onwards and was instrumental in bringing James Gandon to Ireland. He favoured shifting the city centre eastwards from the Capel – Parliament Street axis towards a new axis on College Green with Drogheda Street and the construction of a new bridge linking the two sides. The building was built on slob land reclaimed from the estuary of the Liffey when the Wide Streets Commissioners constructed the Quays. The line of the crescent Beresford Place that surrounds the Custom House follows roughly the line of the old North Strand along the estuary before the construction of the Quays.

Started in 1781, the new Custom House was finished ten years later at a cost of over £200,000. The finished external design consisted of four façades each different but consistent and linked by corner pavilions. The exterior of the building is richly adorned with sculptures and coats-of-arms by Thomas Banks, Agnostino Carlini and Edward Smyth who carved a series of sculpted keystones symbolising the rivers of Ireland.

In the Irish Civil War of 1921-1922 the interior of the Custom House was destroyed when the building was completely engulfed by fire lit by the IRA. The fire blazed for five days, destroying a huge quantity of public records. The heat was so intense that the dome melted and the stonework was still cracking because of cooling five months later and Gandon’s interior was completely destroyed.

http://archiseek.com/2010/1791-custom-house-customhouse-quay-dublin/

It is no wonder Nelsons Column was built when you had someone like John Barry and others in the US and other navy's. So who were they and where did they come from.

So Maritime was very important and who was who and what was what.0 -

http://books.google.ie/books?id=EJC13H8h6PIC&pg=PA195&lpg=PA195&dq=irish+foreign+trade+history&source=bl&ots=DiO8NQ-h_J&sig=LpPEH8FQq6Xi56kogoN-0z_BY1k&hl=en&ei=KF03TbrFKsyFhQfE74SFAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=irish%20foreign%20trade%20history&f=false

This is a very interesting link and and if you check page 195 onwards you will see a map of the trade routes from Ireland for wine c 1615 and going on to summarise the trade relations that Ireland had with Britain in the Pre Famine era.

In 1615 143 ships were involved in wine importation and 31 were Irish 31 Scottish and 51 English.

Cork and Limerick were the premier ports for this with Dublin at 5 position.Spain & France were important trade routes.

By the 1750's Dublin was the premier port with 2360 ships involved in foreign trade and Cork with 732.

So we had a huge centralisation of trade in Dublin with the centralisation of political power and the development of the internal Irish Waterways for internal trade within Ireland and the collection of customs duties and taxes.

You can also see the development of the export of agricultural and textile products.

This is like a Pre-famine "Show me the Money".0 -

Was Dublin a developed port in the 18th century?

In the middle ages, the two harbours in Dalkey were used quite extensively. This lead to a rise in the number of outlaws in the area robbing traders, so a number of fortified houses were built. These are referred to as castles now and Dalkey, Bulloch and Goat castles still remain.0 -

Join Date:Posts: 14594

Fratton Fred wrote: »Was Dublin a developed port in the 18th century?

In the middle ages, the two harbours in Dalkey were used quite extensively. This lead to a rise in the number of outlaws in the area robbing traders, so a number of fortified houses were built. These are referred to as castles now and Dalkey, Bulloch and Goat castles still remain.

Incredibly so. When they built the Grand Canal dock (late 18th century) it was the largest such dock in the world.

The Customs House was built in 1791 and Captain William Bligh (of the mutiny on the Bounty fame) started surveying Dublin Bay in 1800, he also recommended the construction of the Bull Wall. After the completion of the wall in 1842, North Bull Island formed as sand built up behind it.0 -

Dublin Port itself was located up by Wood Quay until circa 1800 and here is a history of the development of the port.

I remember reading somewhere that Dublin was quite a crime ridden place at the time and that Merchants initially did not want to make the move.

Ringsend was a coatal village

The Port

The original Port of Dublin was situated upriver, near the modern Civic Offices at Wood Quay and close to Christchurch Cathedral. The port remained close to that area until the new Custom House opened in the 1790s. In medieval times Dublin shipped cattle hides to Britain and the continent, and the returning ships carried wine, pottery and other goods.

But Dublin Bay presented major dangers for shipping. In 1674 it was described as in its natural state, wild, open and exposed to every wind. Ships frequently had to seek shelter at Clontarf to the north of the city or at Ringsend. In certain wind conditions ships could not reach the city for several weeks at a time. Shipwrecks were common. So in 1716 work began on a bank to protect the south side of the channel at the mouth of the harbour, running from Ringsend to Poolbeg. A committee established by Dublin Corporation that was known as the Ballast Office Committee carried out this work.

The South bank provided only limited protection for shipping and in 1753, after a particularly stormy winter, the bank was replaced with a wall – the South Bull Wall. Bull is another word for strand, and the strands on either side of the mouth of the Liffey were known as North and South Bulls. The Poolbeg Lighthouse at the end of the Bull Wall was lit for the first time on 29 September 1767. It replaced a floating light that had been placed at the end of the wall to warn ships.

To save travel time, passengers and packets of mail landed at the end of the wall, or the Pigeon House, and they were rowed to the city in boats.

Many Dublin merchants were dissatisfied with the running of the port, and in 1786 control of the port was transferred from Dublin Corporation to a new authority-the Ballast Board which was controlled by merchants and properly owners. The Ballast Board was also given control over Dun Leary harbour – modern Dun Laoighaire – and Dalkey Sound. In 1867 the Ballast Board was replaced by the Dublin Port and Docks Board, which continues to run the port to the present day.

Dublin City prospered during the eighteenth century, and trade expanded. Merchants shipped cargos of linen and agricultural produce to Britain and farther afield. Returning ships carried coal and the luxury goods that were in demand in the great Georgian Houses.

By 1800 most of Dublin's trade was to British ports. The shipping channel in Dublin Bay was too shallow for larger vessels, and many ships were forced to unload their cargo at Ringsend onto lighters that could travel upriver.

In 1800 a major survey of Dublin harbour by Captain William Bligh, who is remembered for his role in the mutiny on the HMS Bounty, recommended that the North Bull Wall should be constructed, parallel to the South Bull Wall to prevent sand building up in the mouth of the harbour. He correctly forecast that this would create a natural scouring action that would deepen the river channel. When the North Bull Wall was completed in 1842, sand gradually accumulated along its side until the modern BullIsland emerged.

Until 1800 most trade took place on the south side of the River Liffey, but with the opening of the new Custom House in 1791, port development shifted to the north bank of the river.

The original Custom House Dock opened in 1796. In 1821 it was supplemented by George's Dock, which included large warehouses and storage vaults. These formed part of the Custom House Dock Area. In 1836 construction work began on deep-water berths at the North Wall and this was extended in the 1870's. Further deep-water berths, in the AlexandraBasin opened shortly before World War I and Ocean Pier, to the south-east of AlexandraBasin was completed after World War II. The 1950s brought the first roll-on, roll-off services, and container traffic has increasingly dominated port business since the 1960s. Cargoes have changed in line as the Irish economy has revolved: live cattle have given way to chilled meat; oil is now more important than coal, and the containers carry the products of many of Ireland's high-tech factories.

http://www.ddda.ie/index.jsp?p=629&n=113&a=81

The Customs House itself is a gorgeous building and though built in the late 18th century I often wonder how much of it dates from that period and ,like the GPO what was a rebuild after the 1921 fire.

One of Dublin’s finest 18th-Century buildings, it was almost destroyed during the War for Independence in 1921. However, ships carrying cargoes of dutiable goods, such as wine, tobacco, sugar and tea continued to tie up at the nearby quays. Their cargoes were often stored in warehouses or ’stacks’ attached to the Custom House Dock. In 1840 the building became the Irish headquarters of the Poor Law Commissioners, who carried a major responsibility for relief during the great famine of the 1840s.

In 1872 the Custom House became the headquarters of the Local Government Board or Ireland. The building also housed the Irish Revenue Commissioners. In May 1921, during the Irish War of Independence, the Dublin Brigade of the IRA attacked the building, setting it on fire. They wished to destroy the main tax and local government records as part of their campaign to undermine British administration in Ireland. The fire lasted for five days; all that survived was the shell.

Drunkenness,duelling and public hangings were all part of living in Dublin of the Wine Bottles and that was just the upper classes,

And in the same newspaper: 'Monday se’nnight, Mr. Egan, a reputable citizen, living opposite Bridge Street, in Cook Street, was attacked by a set of villains on the Inn's Quay, opposite that part where the Cloisters formerly were; they took what money he had about him, and two gold chains and seals; nay, gave him a violent blow with a blunderbuss on his head, and abused him otherwise so severely that his life is since despaired of.'

Indeed, even in the day-time pedestrians were not always safe, as we read, still in the same newspaper: The weather these few days past being so remarkably fine, it has tempted the ladies to walk the Circular Road; we therefore caution them not to walk on any part of it that is lonesome; for two ladies, last Tuesday at noon, walking on that part near Donnybrook Road narrowly escaped being robbed by a single footpad, and only for the sudden and fortunate appearance of a gentleman, they certainly would.'

That no lack of severity on the part of the authorities can be held accountable for this prevalence of robberies with violence may be inferred from the following account of an execution at Kilmainham. (The ancient Danish place of execution was Gallows Hills, east of St. Stephen’s Green and south of Lower Baggot Street. A gallows still stood near St. Stephen's Green in 1786, and here the four pirates mentioned shortly, were hanged) 'The execution of five footpads on Saturday last' (25th June 1785) 'was, by an accident, rendered distressing to every person capable of feeling for the misfortunes of their fellow-creatures. In about a minute after the five unhappy criminals were turned off; the temporary gallows fell down, and on its re-erection, it was found necessary to suffer three of the unhappy wretches to remain half-strangled on the ground until the other two underwent the sentence of the law, when they in their turn were tied up and executed.' This extract is a good example of the sentimentalism iii such matters which characterised the period.

Three more executions were carried out at the same place on 26th January 1786. The presence of so much wealth in Dublin, while so many of its inhabitants were destitute, must be held accountable for much of this crime, as we find it noted' in Twiss’s tour that 'footpads, robberies, and highwaymen are seldom heard of except in the vicinity of Dublin.'

In the city, however, scarcely a week seems to have passed in which some burglary or robbery with violence is not chronicled. Such being the condition of the streets, we need scarcely wonder that the roads in the neighbourhood of the city were infested with highwaymen. In a number of the same weekly paper we read: 'The lads of the road were rather unfortunate on Sunday last, and that too on a cruise in which they expected to levy considerable contributions (Donnybrook Road at fair-time), for between the hours of nine and ten, six of them having' stopped a capriole (sic) near Cold blow Lane and called on the gentlemen therein to deliver their money, one of the gentlemen instantly presenting a musket at them they made a precipitate retreat. Their next attack was on a coach, in which unfortunately for them were four Independent Dublin Volunteers, full armed, two of whom, as soon as one of the robbers presented a pistol at the window, jumped out at the other, and after knocking the villains down with the butts of their firelocks, seized them, notwithstanding a desperate resistance, and brought them to town, where after securing five of them for the night, they had them next morning brought before the sitting magistrate, at the Tholsel, and committed to take their trial.'

Indeed, gentlemen belonging to the volunteers often took upon themselves to patrol the streets at night, and thus men of rank might be found discharging the duties now committed to the capable charge of the Metropolitan Police.

That crime was not limited to robberies from houses or from the person is indicated by the frequent arrest of coiners; and in March 1766 four pirates, captured near Dungannon Fort, Waterford, were hanged in St. Stephen's Green, and their bodies suspended in chains on the south wall and afterwards removed to the Muglins, a cluster of small rocks near Dalkey Island.

The dangers of the streets were further added to by the conduct of the 'Bucks' and 'Bloods,' young men of fashion, who founded the notorious 'Hell Fire Club,' the remains of whose clubhouse still form a landmark on the summit of one of the Dublin mountains. They are said to have set fire to the apartment in which they met, and 'endured the flames with incredible obstinacy … in derision … of the threatened torments of a future state.' (Ireland Sixty Years Ago, Dublin, 1851, p.18.)

The conduct of these 'Bloods' may be gauged by the following extract from a contemporary newspaper: 'Three Bloods passing through High Street amused themselves by breaking windows, and on one of the inhabitants complaining of their ill-conduct, they pursued him into his shop, struck him violently, and had the brutality to give his wife a dreadful blow in the face. Two of them were soon obliged to retreat and leave their companion behind, who was lodged in the Black Dog Prison' (Formerly Browne's Castle (Mayor in 1614), converted into an inn, known, from its sign of a talbot or hound, as the Black Dog, and early in the 18th century used as the Marshalsea Prison.)

Many of these ' Bloods' were known as 'sweaters ' and 'pinkindindies'; the former practised 'sweating,' that is, forcing persons to deliver up their arms; the latter cut off. a small portion from the ends of their scabbards, suffering the naked point of the sword to project; with these they prodded or 'pinked' those unoffending passers-by on whom they thought fit to bestow their attentions.

The outrages of these ruffians led to an universal demand for the re-enactment of the 'Chalking Acts.' These Acts imposed extreme penalties on those offenders known as 'chalkers,' who mangled and disfigured persons 'merely with the wanton and wicked intent to disable and disfigure them.' That these provisions were especially directed against young men of the better class is evident from the provision that the offence shall not corrupt the offender's blood, or entail the forfeiture of his property to the prejudice of his wife or relatives.

The practice of wearing swords, then universal with men of rank and fashion, fostered the spirit of aggressive outrage on the peaceable citizens, and is also accountable for the prevalence of duelling, in which the most eminent members of the Bar and Senate commonly engaged. Fitzgibbon, the Attorney-General, afterwards Lord Chancellor and Earl of Clare, fought with Curran, afterwards Master of the Rolls. Scott, afterwards Lord Chief-Justice of the King’s Bench and Earl of Clonmell, had a duel with Lord Tyrawly on a quarrel about his wife, and afterwards met the Earl of Llandaff in an affair concerning his sister.

Nor were the quiet shades of Trinity College free from the practice. The Hon. Hely Hutchinson, when Provost, fought a duel with a Master in Chancery, and his son, following the paternal tradition, fought Lord Mountnorris. In a duel fought on Sunday, 18th November 1787, in the Phoenix Park, the hat of one of the principals was twirled round by his opponent's ball, and the latter received a shot which grazed one of his breast-buttons.

The notorious 'fighting Fitzgerald' made it a practice to stand in the middle of a narrow crossing of a dirty street, so that every chance passenger had either to step into the mud, or jostle him in passing. In the latter event a duel immediately followed. It has been calculated that during the last two decades of the 18th century no less than 300 notable duels were fought.

Both duelling and riotous conduct were greatly fostered by the prevalence of drunkenness, especially amongst the upper classes. Dublin had long had an unenviable notoriety in that respect. An Irish priest, in a Gaelic address to his countrymen from Rome, towards the close of the seventeenth century, styles his native city 'Dublin of the Wine Bottles'.

Winetavern Street is one of the oldest streets of the city; and in the reign of Charles ii., with a population of 4,000 families, there were 1,180 ale-houses and 91 public brew-houses. (Sir William Petty) In 1763 the importation of claret, the fashionable drink of the upper classes, had reached 8,000 tuns, and the bottles alone were estimated at the value of £67,000.

Fathers exhorted their sons to 'make their heads while they were young,' and bottles and glasses were alike constructed with rounded ends, so that the former must perforce be passed from hand to hand, and the latter must be emptied before being set down. The Bar, the Church, the Senate, the Medical profession, even the Bench itself, were alike subject to this degrading excess; and drunkenness was so common, especially amongst the higher grades of society, as to entail no social censure whatsoever.

http://www.chaptersofdublin.com/books/ossory/ossory6.htm0 -

Advertisement

-

Lough Derg Steam Ship The Lady Lansdowne .

In 1833 The Lady Lansdowne was built in sections at the Birkenhead Iron Works (later to be the Cammell Laird foundry). She was the world s first iron ship with watertight bulkheads.

The ship was assembled from parts transported to Dublin by the night mail steamer service from Liverpool , brought by canal barge from Dublin and via Lough Derg to Killaloe. This little Paddle Steamer plied her trade on the midland lake for nearly 50 years she now sadly lies buried somewhere under the Ballina Marina.

http://books.google.ie/books?id=CaL2e7MJZ1EC&dq=Lady%20Lansdowne%20steamer&pg=PA479#v=onepage&q&f=false

Her Specs

http://www.irishshipwrecks.com/shipwrecks.php?search_name=Lady+Lansdowne0 -

It lies submerged in Lough Derg and a few years ago there was talk of raising her and restoring her as a tourist attractionLady Lansdowne

Lady Lansdowne, the world’s oldest surviving iron paddle steamer

The Lady Lansdowne was a paddle steamer of 148 tons, 130 feet in length and 17 feet wide which was built in sections at the in Birkenhead Iron

Works in 1833 (later to be the Cammell Laird foundry). She was the world’s first iron ship with watertight bulkheads and is the world’s oldest surviving iron paddle steamer. She was given the yard ‘number 1’ by Laird as this vessel was the first powered iron ship to be constructed at the Birkenhead Works. These features make the ship of international importance in terms of shipbuilding. At the end of her working life the ship was beached in the shallows on the Ballina side of the Shannon River and left there on the site of what is now the Derg Marina. It is estimated that the date this took place was 1867-1868. As the vessel is more than a hundred years of age it has the protection of the 1987 Monuments Act.

The Lady Lansdowne was the largest steamer to work on the Shannon, and with her two forty-five horse power steam engines she was capable of towing up to four barges. On account of her size she could not venture to Limerick via the canal to the south of Killaloe or travel on the Grand Canal, so the ship was assembled from parts brought by canal barge from Dublin and via Lough Derg to Killaloe. She was built in a wet-dock that had been constructed adjacent to the Pier Head at Killaloe a few years earlier. In the 1820s William Laird, a boiler maker, who had moved from Scotland to the Mersey, was joined by his son John and they started to build ships from iron. In 1833 they received the order for the largest ship that was to work that century on the Shannon. At this time a regular passage between Liverpool and Dublin was being run by the City and Dublin Steam Packet Company (CDSPCo). It was this company who ordered a large iron ship from Lairds, to be named The Lady Lansdowne.

Sections of The Lady Lansdowne were delivered to Dublin by the night mail steamer service from Liverpool on 20 September 1833 and by 24th September, the twenty men and six boys who came over on the CSSPCo steamer Birmingham with the necessary tools and ship sections left Portabello Harbour on the Grand Canal for Shannon Harbour, then on a further barge for Killaloe.

According to newspaper reports The Lady Lansdowne was launched at Killaloe on the 4th March 1834. She had five distinct compartments made of wrought iron partitions that would prevent sinking should a section become flooded. Being an iron ship she would float at a shallower draft than a similar sized wooden vessel. She therefore had an advantage in entering shallow harbour areas on the Shannon River and in Lough Derg.

Such a vessel would also have a corresponding ability to carry more cargo. The engines she received had been removed from another of the Company’s ships, The Mersey, which had recently been re-engined.

The Lady Lansdowne could tow up to four barges (also known as lumber boats) and was an important component of commerce at this time as goods, livestock and passengers could be ferried around Lough Derg. For example cattle could be towed in a barge to Portumna by a large steamer, to Shannon Harbour by a smaller steamer and then taken by canal to Dublin for export, within three days.

Barges also carried slate from the quarries at Garrykennedy and Deer Harbour (known as ‘Killaloe slate’). This slate was finished in Killaloe at the Slate yard. At this time the quarries and yard employed 350 to 400 men with an annual export of seven to ten thousand tons each year, and brought via the Grand Canal to Dublin and to England. In 1840 records show that passenger movements from Killaloe were more than 3,500 passengers and much of this traffic could be attributed to The Lady Lansdowne. This ship worked a six-day week steaming from Killaloe at 0900hrs, leaving after the arrival of the fly-boat from Limerick and returning that evening. She steamed up-lake to Williamstown on the western side of Lough Derg and then on to Portumna at its northern end to arrive in the afternoon. Over the six-day working week she was in service for 49 hours.

The fuel used initially was coal but in the 1840s peat began to be used and The Lady Landsdowne converted to this cheaper fuel, almost certainly supplied from Coos Bay and Rossmore on the western side of Lough Derg. She could reach Portumna from Killaloe in 2 hours and 15 minutes.

Because of her size The Lady Lansdowne was confined to working on Lough Derg until improvements were made to the river and new locks built at Meelick and Athlone in the 1840s. Her first visit to Athlone in 1849 was a novelty. There was now competition, arising from the development of the railway network in Ireland, this resulted in less trade by water although a continued passenger service did take place for a while.

The railway company (The Midland and Great Western Railway- MGWR) bought two vessels The Duchess of Argyle and The Artizan and these went into competition with the CDSPCo and caused them to discontinue their passenger service in 1859.

By 1860 the railway companies MGWR and The Great Southern and Western Railway (GS&WR) agreed to discontinue their passenger service. Yet The Duchess of Argyle still provided a service between Killaloe and Athlone three times a week. This service was short lived and soon after in 1865 the passenger vessels, including The Lady Lansdowne were described in a report, to the Select Committee on Navigation, as being in a wretched state and rotting at Killaloe. Most of these vessels were tied-up or moored at this time and were unlikely to have had much subsequent use.

Photographs from about 1900 shows a ship on the Tipperary side almost opposite the Pier Head.

http://www.marina.ie/Lady%20Lansdowne/Lady%20Lansdowne.htm

Here is a link to the Historical Waterways of Ireland Site which has loads of links and pictures off it .

http://irishwaterwayshistory.com/abandoned-or-little-used-irish-waterways/

http://www.hooksandcrookes.com/newsarchive.htm0 -

When it comes to Irish Maritime History there are a few issues we dont kind of look at. Here I am more interested in the maritime tradition then the political issues that go with it because we know loads about those.

Emigration and transportation, military, and the administration of the empire.

For example, I know that c 1800 members of my family went to Newfoundland , others migrated to New Orleans and Buenos Aires. As I understand it some left as early as 1770.

A great uncle visted Newfoundland sometime in the 1920's -found it too cold apparently and came home.Irish emigration – the 17th & 18th century

The earliest waves of Irish emigration date to the second half of the 17th century and the aftermath of the Cromwellian era. Most were Catholics. While significant numbers went voluntarily to settle in the West Indies, even more were transported there as slaves. The alternative route, which attracted many from counties Waterford and Wexford, was to Newfoundland.

To the typical Irish Catholic of the 17th and 18th century, the very notion of emigration went against the old Celtic traditions of extended family and clan relationships. To leave your family, and your homeland, was considered an unbearable exile. For this reason, an ambition to find a better life overseas did not trouble the majority of Ireland's population, no matter the poverty they currently lived in or the oppression they suffered as a result of their faith. In any case, where would they go? Catholic immigration to North America was forbidden by law until after the War of Independence. And since most lived on the poverty line (at best), how could they afford to pay for their passage? For most Catholic Irish famiiies, emigration was simply not on the agenda. Those that found the means and chose to sever ties with the old country usually sailed from Cork or Kinsale and small

settlements evolved in Virgina and Maryland.

In the northern counties of Ulster, however, a different attitude held sway with a sizeable proportion of people.

Presbyterians, most of whom had Scottish ancestry, had also suffered discrimination in Ireland but they were not inhibited to the same degree by 'ancestral' connection with the soil. They sincerely believed they would find tolerance, freedom and happiness in North America.

They were also, to varying extents, more economically independent than their Catholic neighbours. Many were artisans, shopkeepers, or young professionals, and some worked in the Irish linen trade. These early waves of Irish emigration were often in response to economic peaks and troughs.

Up to 1720, when New England was the destination of choice for most, the flow was steady but numbers were not large. Numbers rose at the end of that decade and then dropped again.

A famine in the early 1740s saw renewed interest in Atlantic passage, and Irish emigration never really subsided afterwards. In 1771-1773, more than 100 ships left the Ulster ports of Newry, Derry, Belfast, Portrush and Larne, carrying some 32,000 Irish immigrants to America. Meanwhile, a similar number set sail from Dublin, Cork and Waterford alone. Some of these would certainly have been Catholics. By 1790, the USA's Irish immigrant population numbered 447,000 and two-thirds originated from Ulster.

Back in Ireland, the population had grown from only 2.3 million at mid-century to as much as 5 million by 1800. The vast majority lived in poverty.

Irish emigration – the 19th century

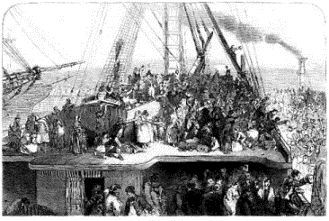

Summary: At least 8 million men, women and children emigrated from Ireland between 1801 and 1921. That number is equal to the total population of the island in the fourth decade of the 19th century. The high rate of Irish emigration was unequalled in any other country and reflects both the overseas demand for immigrant labour and the appalling lack of employment and prospects for the average Irish person.

19th-century emigration from Ireland is usually broken down into three distinct phases:- 1815-1845, when 1 million left;

- 1846-1855, when 2.5 million left; and

- 1856-1914 when 4 million departed.

About 80% of Irish immigrants who left their homes in this period were aged between 18 and 30 years old.

As the figures above suggest, Irish emigration levels up to 1847 did not materially reduce the population of Ireland. But in that year, the first after the pototo harvest had failed so spectacularly, the exodus really began. According to figures collated 15 years later, some 215,444 persons emigrated to North America and other British Colonies in that one year alone. This doubled the previous year's figures for Irish emigration.

Between 1841 and March 1851, North America was the most popular destination while some 300,000 went to Australia. Irish emigration direct to New Zealand did not get underway until later. An estimated average of 2,000 people emigrated there between 1871 and 1920.

http://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-emigration.html0 -

A little nugget - Columbus had an Irish Pilot on the first part of his first Westward journey.

McFineen Duff a kerry chieftian in the 2nd half of the 16th century collected £300 a year for fishing rights of the Spanish with c 600 fishing vessels seen off the Kerry coast.

http://books.google.ie/books?id=I2zNMo8YTDEC&pg=PA62&lpg=PA62&dq=irish+seafarers&source=bl&ots=bL2U7m-HXL&sig=OZ3IzZ28GgJgJ3YTNuQHTwnwPcs&hl=en&ei=xMw8Td-HF8mWhQeFuOSxCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBcQ6AEwADgy#v=onepage&q=irish%20seafarers&f=false0 -

So who was Columbus's Irishman - his name was William and he is listed among those who died in Hispaniola in the CarribeanChristopher Columbus: List of Officers and Sailors in the First Voyage of Columbus4. Those Who Were Left In Hispaniola, And Perished, Most Of Them Murdered

By The Natives: -Guillermo Ires, [qy. William Irish, or William Harris?], of Galney

[i.e. Galway], Ireland.

http://history-world.org/Columbus,%20List%20of%20Sailors.htm

Page 83 - gives the lore about Columbuses Irishman

http://books.google.ie/books?id=UOEWlpeZ708C&pg=PA83&lpg=PA83&dq=irish+sailors+%26+columbus&source=bl&ots=1eWU1KW0rE&sig=VWcml-boSoz_svyZvnw8qoO-g3Q&hl=en&ei=tf09TZCiDKSShAeZ4PmVCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=irish%20sailors%20%26%20columbus&f=false

Other sources say that Columbus was in Galway[FONT=geneva, arial, helvetica]Christopher Columbus (1451-1506)

By Brian McGinn [/FONT]

Navigator. Both oral and written traditions claim Irish connections for the Italian-born explorer in the service of Spain. A local belief in Galway, for example, holds that Columbus attended mass there in St. Nicholas’ Church. According to historian David B. Quinn, Columbus certainly visited Galway prior to his first American voyage, most probably in 1477. On the Irish shore, the visitor viewed an exotic discovery: the drifting bodies of a man and woman of extraordinary appearance, who may have been Inuit (Eskimo) voyagers lost at sea.

An Irish sailor, who appears in Spanish records as Guillermo Ires, natural de Galney, was thought to have accompanied Columbus to America in 1492, and to have perished at the settlement left behind on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. With his name variously translated as William Ayres, William Eris, William Harris, or simply William of Galway, the obscure seaman has appeared in many popular histories as the first documented Irishman in America.

This appealing story has not withstood rigorous scrutiny. The American scholar Alice Bache Gould, who spent decades researching the life stories of Columbus’ crewmen in the Spanish archives, concluded that Guillermo Ires never sailed with Columbus. Although the Irishman’s name did appear on an early--and unreliable--list of the men left on Hispaniola, Gould found that Guillermo Ires was still alive in Europe several years after his alleged death in America.

http://www.illyria.com/irish/mcginn_columbus.html

Of course, just cause the Gould Woman decides she does not believe the list is no proof.

Columbus needed an Irishman and the likelyhood of being helped by 2 Galwaymen called William never occured to her.

And theres more - Sir Walter Raleigh had Irish Sailors

Coming to America

A popular legend of Ireland and among Irish Americans is that of St. Brendan the Navigator. This monk is believed to have reached the shores of North America almost one thousand years before the voyage of Christopher Columbus. William Ayers, a native of Galway, arrived in the West Indies on Columbus’ first voyage. He was one of forty sailors who remained on Hispanola.

Although the great Irish Exodus to North America would not take place until the nineteenth century, Irish began coming to the Americas as early as the 1500s. When Sir Walter Raleigh reached the “new world” in the 1580s, many members of his crew were from Ireland, including Irish sailor John Nugent. Later, in 1677, an Irish immigrant named Charles McCarthy led forty-eight Irish immigrants to establish the colony of East Greenwich in Rhode Island. These early immigrants were predominately men, motivated by the promise of land, wealth, and religious toleration across the Atlantic. Many immigrants, however, were forced to find new homes because of the dire circumstances in which they lived in Ireland. Convicts or exiles from religious wars often escaped to America in the hopes of freely practicing their religion, and many served as indentured servants to wealthy settlers.

http://www.cabq.gov/humanrights/public-information-and-education/diversity-booklets/irish-american-heritage-in-new-mexico/introduction-history

And the Eskimos/Inuit

It appears to come from a marginal note by Columbus in Latin in his copy of Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi.Men of Cathay have come from the west. [Of this] we have seen many signs. And especially in Galway in Ireland, a man and a woman, of extraordinary appearance, have come to land on two tree trunks [or timbers? or a boat made of such?]

Not that much to be skeptical about. Galway was very much a part of trade routes with Europe (hence the Spanish Arch) so it's not inconcievable that Columbus would be here. It's also known that Native American canoe burials would be encountered occasionally by fishermen off the west coast, and that Columbus would have had the oppurtunity to see or hear about these while visiting Galway

http://www.reddit.com/r/ireland/comments/dtk2o/til_that_in_1477_christopher_columbus_visited/ .

These events would have been hugely significant as they were physical proof that Chris was on the right track.

Some people might have viewed him as a crop circle UFO chasin weirdo.0 -

Advertisement

-

A very interesting account of wrecks and salvage at this west Waterford Village including salvage and decoration of the Lifeboat Crew by King George in 1911, and the sinking of vessels by submarine in 1917.

Ardmore was really on the trade route.

Perkin Warbeck is reputed to have stayed there in 1497 on his way to persuade Waterford to support him against Henry VIIIArdmore Memory And Story - The Sea

8. Shipwrecks

Previous Page | Next Page Down through the years, many a good ship met her doom along the coastline from Ardmore. My terms of reference concern the 20th century in Ardmore, but readers will probably be interested in the list of 19th century ship wrecks in the neighbourhood, and also the very interesting account of Perkin Warbeck's engagements.

Down through the years, many a good ship met her doom along the coastline from Ardmore. My terms of reference concern the 20th century in Ardmore, but readers will probably be interested in the list of 19th century ship wrecks in the neighbourhood, and also the very interesting account of Perkin Warbeck's engagements.

1823 Hope (a Youghal ship)

1850 Grace of Newcastle

1860 Echo

Peig Thrampton (year unknown)

1865 Certes (of Malta)

1865 Sextus (of Malta)

1875 Scotland

1881 Elizabeth of Whitehaven in Whitingbay

1895 Jeune Austerlitz of Cardiff

1998 Dunvegan.

The above list of ships and the account of Perkin Warbeck's adventures in Waterford are taken from “Shipwrecks of the Irish Coast” 1105-1993 by Edward J. Bourke.

On the 23 July 1497 Perkin Warbeck pretender to the throne of England and Maurice, Earl of Desmond besieged Waterford with 2,400 men. Waterford was held by forces loyal to the king. Eleven ships arrived at Passage East and two landed men at Lombards Weir. One enemy ship was bulged and sunk by the ordnance from Dundory, Warbeck escaped to Cork and there to Kinsale pursued by four ships. He then went to Cornwall, still followed by ships loyal to the throne. A cannon with reinforcing rings typical of the period was dredged from the Suir and is on display in Waterford.

Incidentally, in an account given to the Royal Society of Antiquarians of Ireland by Westropp in 1903, he says “In 1497, Perkin Warbeck, the pretender to the English crown occupied Ardmore Castle and sent thence to summon the city of Waterford to surrender. At Ardmore, he left his wife in safety and marched to besiege the city that refused his claims.” This account is somewhat at variance with the previous one but is nevertheless interesting.

According to the Ardmore Journal 1988, seventeen ships were lost off Ardmore 1914-1918, fourteen of them in 1917. In most of these cases, the attack occurred ten miles or more out at sea and the survivors were picked up and brought elsewhere, so the incidents passed unnoticed in Ardmore. The Folia and the Bandon, however, were quite close inshore when torpedoed.

The wreck of The Teaser on Curragh strand in March 1911 has been well documented. This abbreviated account is based on an article by Donal Walsh in ‘Decie’. September 1982. The Teaser was bound for Killorglin, Co. Kerry with a cargo of coal and left Milford Haven on 16th March. She had a crew of three and all three were lost.

A very strong south-easterly gale had blown up and the boat was blown on to the rocks at Curragh. John O’Brien sighted her at 5am on 18th March, got as close as possible and saw three men on board but could not communicate with them on account of the noise of the storm. He reported to the Ardmore Coastguards and a message was sent by telegraph to the Helvick Life-boat. Three coastguards, Thomas Bate, Richard Barry and Alexander Neal arrived in the meantime with the rocket apparatus. All three men on board the boat had taken to the rigging. Five rockets were fired; some missed but the men on board failed to operate the others which did reach the boat. Coastguards Barry and Neal tried to swim to the ship along the rocket line, but failed in the attempt.

Fr. O’Shea C.C. Ardmore then came into the story. At his instigation a boat was brought from Ardmore by horse and cart and he called for volunteers to go out to the Teaser. Coastguardsmen Barry and Neal, Constable Lawton, William Harris of the Hotel, Patrick Power and Con O’Brien farmers and John O’Brien fisherman answered the call and were able to get alongside the Teaser by hauling themselves along the rocket line and rowing at the same time. Wm. Harris, Constable Lawton and the two coastguards boarded her. The men on board were still alive but only barely and unfortunately they dropped one survivor into the sea while taking him down, but Barry and Neal dived in and rescued him. Fr. O’Shea administered the last rites. The bodies were laid out in Michael Harty’s barn and according to an account by Johnny Larkin, Curragh, two were buried in Ardmore and the Captain’s body brought home to Wales.

The incident got great publicity and on 13th April 1911, the Committee of Management of the R.N.L.I. meeting in London, awarded the Gold Medal of the Institution to Fr. O’Shea and appropriate awards to all the other participants. The Carnegie Hero Fund trust awarded all of them as well, and then on 2nd May 1911, Fr. O’Shea and his party were decorated by King George at Buckingham Palace.

On 12th December 1912, the Marechal de Noailles of Nantes left Glasgow for New Caledonia, a French Penal Island in the South Pacific. She carried a cargo of coal, coke, limestone and railway materials. There was a crew of twenty besides the Captain and First and Second Mates. The beginning of the voyage was eventful with seven days being spend at Greenock waiting for an improvement in the weather; a further seventeen days off Aran Island, Scotland; then venturing down the Irish Sea but about sixty-five miles north of Tuskar having to retrace the voyage, this time to Belfast Lough. At last, they really got going and were a few miles from Ballycotton, when the wind strengthened. They turned about; the Captain fired distress signals; eventually the ship was blown ashore three hundred yards west of Mine Head.

Helvick Lifeboat responded to the distress signals, but could not approach her. The keeper of Mine Head lighthouse, Mr Murphy telephoned the Ardmore Coastguards, and the rocket crew assembled. Coastguards Barry and Neal, J O’Brien, J Mansfield, J McGrath, P Foley, J O’Grady, M Curran, J Quain, P Troy, M Flynn, Con Byron, Sergt Flaherty, Constable Walsh and Fr. O’Shea. As the roads were too bad for the rocket wagon to travel, the crew carried the apparatus fourteen miles on foot to the wreck and arrived about 2am. The apparatus was assembled; the first rocket passed over the vessel, but the crew did not know how to deal with it.

Meanwhile, one sailor had been washed overboard and J Quain encountered him at the bottom of the cliff and explained the workings of the rocket apparatus, by sign language. With the aid of a megaphone, he instructed the rest of the crew still on the ship how to work the Breeches Buoy, and all the men came ashore.

Four had been injured during the night by flying spars and were unconscious and anointed by Fr. O’Shea. All were eventually taken to Dungarvan. Some months later, Fr. O’Shea had a most appreciative letter from Captain Huet, Morlaix.

No doubt, it was an unforgettable experience for the Ardmore men, tramping for hours in the dead of night with their apparatus which looked as if it wasn’t going to have the desired effect; then the joyful break-through the language barrier and being surrounded by a group of men “quacking like ducks” as one of them put it. So it is not surprising that the name Marechal de Noailles is remembered years afterwards in Ardmore. (The most of this account is taken from the article by Donal Walsh in Decies. September 1982.)

The Nellie Fleming from Youghal figured twice in shipwreck stories. The first Nellie Fleming went aground on Curragh strand in December 1913, having in the mist mistaken their location. The Ardmore coastguards and Youghal and Helvick Lifeboats were in attendance, but the crew hoped to get her off. Finally, when the water gained on the boat, the crew abandoned ship and returned to Youghal by the life-boat. Next morning, the owner came and concluded that the boat was going to be a total wreck and handed her over to Lloyd Agent, Mr Farrell of Youghal.

A group of locals bought the cargo of coal from him and formed a coal company to resell the coal. Jack Crowley with three other lads recalls being sent by his father, the local school master to bring home ¼ ton coal for the school, by donkey and cart. They weren’t upset being at the end of the queue which comprised farmers from Grange and Old Parish coming for the cheap coal. He referred jokingly afterwards to the “Curragh Coal Co-op” as being the first Co-op in Co. Waterford. (This account is condensed from that of James Quain in the Ardmore Journal.)

An interesting fact which emerges from the story of the Teaser and of the Marechal de Noailles was, the crew’s ignorance of the life-saving equipment and how to use it; and also of the fact that people in general were ignorant of the principles of life-saving and resuscitation. A bystander in Curragh has said, at least one of the men was still alive while being brought ashore, but clearly, nobody knew how to deal with the situation and apply artificial respiration.

The Folia (6704 gross tonnage) was sunk off Ram Head in March 1917. Seven of the crew were killed in the explosion; the others took to the life-boats and eventually made their way to Ardmore and reached it as last mass had finished, so there was a large crowd around. The R.I.C. took a roll-call outside the Hotel on Main Street. Many people provided food and clothing and arrangements were made to transport them to Dungarvan, where they were taken that evening in a fleet of cars.

In the Ardmore Journal 1988, James Quain in his account of the incident includes an interesting letter from a member of Dr Foley’s household, Glendysert. “All the people took some of the crew to each house. We had five, three English, one American (the doctor) and one Dane. Some were without boots, all without socks, some without coats and so on. After looking after creature comforts (they were of course without food since the night before, with the exception of the biscuits, with which each boat is provisioned) they were anxious for music, so we put on the gramophone for them. I believe they danced and sang up at the convent. Sr. Aloysius played for them.” The letter-writer also says of the attack on the boat, “When they had taken to the boats, the captain of the submarine who was very courteous, came up to them and told them they were all right and to row into Ardmore, 4½ miles away.”

The article by James Quain goes on to say, “Some months passed before the salvage began to float in. Wooden barrels of oil were picked up by the Receiver of Wrecks and later sold. Sides of ham, loose or in boxes, I cu yard in size came into Ardmore and elsewhere along the coast. Large slabs of tallow about 3 feet by 2 inches thick floated ashore in boxes or single slabs. These were seized by the locals and used for making candles as paraffin oil for lamps was very scarce.

As the Folia is such a large vessel 430ft in length and is located only four miles off Ram Head, it has been dived on many times, although it lies in about 120ft of water. According to Lloyds, the ship was carrying a general cargo, but a large number of brass items has been recovered.

According to the Dungarvan Observer 8th March 1980 “During the Summer of 1977 two salvage vessels ‘Taurus’ of Hamburg and ‘Twyford ‘ of Southampton were working on the lines.......... Recently in Ardmore, divers were seen in the area.......... Divers from Tramore, West Cork and Dungarvan were involved.......... One of the divers Cormac Walsh said they were working as a hobby on another wreck the ‘Counsellor’ which is hundreds of yards away from the Folia and about 130ft deep.

The Bandon (summary from Ardmore Journal 1988). On 12th April 1917, the Bandon sailed from Liverpool for Cork under the command of Captain R.F. Kelly. On the evening of Friday 13th an unlucky day to be at sea, when the ship was off Mine Head, she was struck by a torpedo on the port side and immediately began to sink, with a loss of twenty-eight lives. The four survivors including the captain were in the water for over two hours. Following a message from Mine Head lighthouse, they were rescued by motor launch and taken to Dungarvan. The explosion was heard clearly on shore, and when the smoke had cleared away, the Bandon had disappeared.

The late Johnny Larkin of Curragh wrote his own account. “On the 13th of April 1917, she was sunk 2½ miles south of Mine Head and about four miles from the Curragh shore. I saw her go down in less than half a minute. She was sunk by a submarine, according to the British, but I think the crew did not know what sank her. She went so quick some said she was sunk by a mine or two mines tied to a chain.

The spring of 1947 will long be remembered in Ardmore for its severity. Snow rarely falls here, but that year, the place was absolutely snowed in, with men having to go out and dig trenches in order to let the bread van in.

It was at this period that the S.S. Ary, a ship of 40 tons displacement left Port Talbot , with a cargo of coal for the Railway Company at Waterford. The Captain was an Estonian, Capt. Edward Kolk and the fourteen other crew members were of various nationalities. The weather worsened and the cargo of coal began to shift and in spite of all efforts, the list got worse and the crew had to abandon ship somewhere off the Tuskar Rock. They had no oars, no food or drink in the two life-boats.

When Jan Dorucki, the sole survivor woke from sleep he found himself surrounded by dead men, who had all died from exposure and being frightened, he pushed them all overboard. For two days more, the life-boat drifted on and eventually came ashore on the Old Parish Cliffs. Jan was in a dreadful condition, but somehow he managed to climb the cliff and dragged himself to Hourigans’ farm-yard, where the dog found him at dawn. He was brought in and wrapped in a blanket and eventually brought to Dungarvan Hospital. A point to remember is that people did not have telephones nor motor-cars at this period.

Cait Cunningham who was on duty at the hospital, when he arrived gave a heart-rending account of it to Kevin Gallagher who has had it published in his column in The Dungarvan Observer. He remained in a critical condition for days and eventually had to have both his legs amputated. During his stay the language barrier proved a great obstacle, but Nurse Cunningham says, a Polish officer arrived from England and so did Jan’s father; and a Polish phrase book and dictionary they brought, were a wonderful help. He returned to Poland after twelve months.

Meanwhile, the bodies of Jan’s companions were being washed in along the coast from Ardmore to Knockadoon. Willie Whelan of Ballyquin found a body on the beach; he brought it to Ardmore, where it was identified as being that of a Spaniard and was buried in Ardmore graveyard.

During the course of that week-end, the other eleven bodies were brought to Ardmore. According to the inquest, they all died of exposure. I remember seeing the coffins stacked up outside the Fire Station. Later on, they were buried in one grave in a corner of the graveyard. The funerals began at 2pm and each coffin was brought up in turn, in the hearse provided by Kiely’s of Dungarvan. Rev Fr. O’Byrne P.P. and Rev. Warren, Rector of St. Paul’s said the graveside prayers.

Fifty years later on November 1st 1997 Canon O’Connor of Ardmore and Rev Desmond Warren (nephew of the Rector of fifty years before) presided at prayers at a newly refurbished grave and headstone erected by the people of Ardmore. Donald Lindenburn, whose father George was in the Ary came from Swansea; he had his father’s naval record book; he had seen war duty on the Atlantic and the Pacific, so it was tragic and ironic that he should perish on the short trip across the Channel to Ireland. He placed a family wreath on the grave and so did Jim Spooner from the British Merchant Navy. The service concluded with the lone piper's lament by Mr Michael McCarthy.

Later on in the afternoon, John and Billy Revins took the Welsh visitors out on Ardmore Bay, where another wreath was set afloat to the memory of the fourteen members of the Ary crew. These last paragraphs have all been condensed from Kevin Gallagher's account in the Dungarvan Observer.

The Fee des Ondes a French boat was wrecked in Ardmore in October 1963. It was blown in to Carraig a Phúintín and all efforts of Youghal Life-boat to get her off failed. It was with difficulty, the skipper was persuaded to leave, even though the boat had been holed by the rock and began to take in water.

The Cork Examiner of October 28th 1963 says “Two Frenchmen were rescued by life-boat, and seven crew, one of fifteen years old on his first voyage, by rubber raft in a sea drama, off the beach at Ardmore, Co. Waterford yesterday morning. They were the crew of the 300 ton trawler Fee des Ondes out of Lorient, which went aground in poor visibility just before dawn and which was subsequently severely damaged by rocks and pounding waves.

Youghal life-boat had been launched and life-saving rocket man, Jim Quain, was alerted, raised the alarm and fired the maroon which brought out the full crew. The crew came ashore by rubber dinghy but the Captain P Maletta and his mate E Dantec refused to abandon ship for a considerable time. They were all taken to the village and Mrs Quain provided hot food and clothing. An abiding memory of hers, is, besides the salt water even seeping down the stairs, was the incident of the crew sitting around her dining room table where a cask of Beaujolais from the vessel, containing about twelve bottles or so was ensconced. They asked her for glasses and imbibed the lot without as much as asking her would she like a glass, never mind a bottle. Lloyds later offered to recompense them for their hospitality, but they declined to accept.

http://www.waterfordcountymuseum.org/exhibit/web/Display/article/120/8/

There is a lot of supersticion attached to the sea and here are accounts of phantom boats

.9. Phantom Boats

Previous Page | Next Page

In the Ardmore Journal of 1991, James Quain has a very interesting article on ‘Phantoms of the Sea’.

He tells first of the phantom boat seen by his grand-father Jamsie Quain about 1900. It was winter and he was tilling land out the cliffs when he saw what seemed a ship’s life-boat out to sea with about a dozen men rowing and another steering and he saw them change seats a few times. He called one of the coastguards and they both went back to the cliff. The boat was drawing near and almost below them; the crew looked cold, wet and hungry but strangely did not respond when the two onlookers waved and called. Suddenly, to their amazement, the boat altered course and set out to sea again. It seemed unbelievable, that an exhausted crew could head out from sheltered waters into the open sea.

Jamsie and the coastguard hurried to the pier and got a crew together, including Pat Troy and Maurice Flynn. They got the sail up and soon began to catch up on the boat heading towards Mine Head. They got within almost 200 yards of it but could not get any nearer; they shouted but got no response. Maurice Flynn said “Turn back, Quain, or we’ll all be lost. We’re following dead men”, so they reluctantly did so. The coastguard telephoned Mine Head lighthouse and alerted the rescue services along the coast, but the boat was never seen again.

Jimmie Rooney had the story both from Maurice and Jamsie. They said they were only just off the corner of the head on the return journey, when a sea broke on top of Seán Spán, “a big wave that would drown a liner, Seán Spán is a sunken rock off Ardmore Head, where a Spanish ship was wrecked one time. We often got nets caught there at low spring tide.” Some days later, they heard a large vessel had been lost out at sea, about a week previously.

Jimmie Rooney, Paddy Downey, Mikey Lynch and Jack Farrissey all give graphic accounts of the phantom boat seen in February 1936.

Jimmie and his crew were putting out nets at the Head on a Sunday night when “we saw this vessel bearing down on us from the south-east and thought it was the bailiffs launch coming out from Youghal” and they began pulling in the nets. We waited at Goílín na Rínne but there was no sign of the ship coming round the Head, so after a while, we began to put out the nets again and put Paddy Flynn ashore and we rowed round the Head” but none of us saw anything.

Within a week, a big storm came and the Nellie Fleming was lost.

Paddy Downey with Tom Harty and Johnie Brian from Curragh were out at Faill na Daraí putting out the nets, when they saw what they thought was the Muirchú.

Mikey Lynch and Jack Farrissey were at the Clais under the well, putting out the nets also that Sunday night, when they saw the big boat coming from the Head towards them. They too thought it was the Muirchú and hastily made for the pier, where they met Paddy Downey soaked to the skin, “with his new blue suit destroyed by the salt water”.

Willie Roche from Monatrea tells of the phantom ship that came into Caliso Bay during the Great War. It was near the old Moylan family home down near the beach, and came so close that those watching on shore thought she’d go aground. They could see the naval men in uniform going about the deck. The ship came along by Cabin Point and at Carthy’s Cove disappeared off out. A few days later, the news came that Mike Moylan on HMS Carturian was dead. He is buried in Ardmore graveyard just outside the cathedral at the S.E. corner.

These accounts are condensed from the Ardmore Journal of 1991.

Another maritime ghost story concerns Martin Troys' grandfather from Curragh who was drowned while sailing home from Youghal in 1886. A neighbour, John Corbetts grandfather was digging potatoes at about 10am and saluted Seán Treo as he passed by, but he got no reply from him and reported this at home. It transpires that Seán Treo was dead when his neighbour met him0 -

Read a book a good few year's ago which i would recommend to anyone with a interest in irish maritime history,think it was called the long watch,cover's the beginning's of the likes of arklow shipping,irish shipping before it was sold out & irish ship's during world war 2 which had some funny stories.unfortunately in the next few decade's there won't be anything left to write about as we lose more & more ship's to flag's of convenience with about half of arklow shippings ship's now dutch & of course irish ferries now flying the cypriout flag,it sadden's me as a merchant seaman.0

-

irishship.com has some articles on famous irish mariner's & ship's,worth a look & there's even a pic of me on there.look for the tall dark handsome fella,i'm somewhere behind him:D0

-

Join Date:Posts: 14594

hairy sailor wrote: »Read a book a good few year's ago which i would recommend to anyone with a interest in irish maritime history,think it was called the long watch,cover's the beginning's of the likes of arklow shipping,irish shipping before it was sold out & irish ship's during world war 2 which had some funny stories.unfortunately in the next few decade's there won't be anything left to write about as we lose more & more ship's to flag's of convenience with about half of arklow shippings ship's now dutch & of course irish ferries now flying the cypriout flag,it sadden's me as a merchant seaman.

Sounded like a good read so looked it up

The long watch, the history of the Irish Mercantile Marine in World War Two, Frank Forde

Available in your local library!

I was told that the average age of crew on an Irish Shipping ship was around 26 in the 70s. Some of the stories I heard were fairly typical of crews on all ships though 0

0 -

Take a vist to www.irishships.com -its choc full of lots of stuff jast as Hairy Sailor says.

Here is just copy of one part of one section and behind each section is a huge amount of detail.

And the links below work0 -

hairy sailor wrote: »irishship.com has some articles on famous irish mariner's & ship's,worth a look & there's even a pic of me on there.look for the tall dark handsome fella,i'm somewhere behind him:D

And there's more on Famous Irish Mariners

The links work

www.irishships.comFamous Irish MarinersWILLIAM BROWN

FOUNDER OF THE ARGENTINE NAVY JOHN BARRY

FIRST COMMODORE AMERICAN NAVY CAPTAIN ROBERT HALPIN

MASTER OF THE

"GREAT EASTERN" SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON

Mariner and Polar explorer JOHN HOLLAND

INVENTOR OF THE MODERN SUBMARINE THOMAS CHARLES JAMES WRIGHT

FOUNDER OF THE ECUADORIAN NAVAL SCHOOL SIR FRANCES BEAUFORT

DEVELOPER OF THE WIND FORCE SCALE BARTHOLOMEW HAYDEN

NAVAL OFFICER IN BRAZIL PETER CAMPBELL

NAVAL OFFICER AND FOUNDER OF THE URUGUAYAN NAVY0 -

Grainneuaile her nickname means "Bald Grace" came about as she cut her hair to get on ships and carried on the business of any chief or clan at that time.

Calling her a Pirate is a bit of a put down as she was very skilled and educated. When she met Queen Elizabeth they communicated in Latin - the language of diplomacy at that time.

How she learned her trade.

A brief biography

[/SIZE]

[SIZE=+1]

[/SIZE]

[SIZE=+1]Queen Elisabeth meeting

[/SIZE]

[SIZE=+1]

[/SIZE]

[SIZE=+1]

[/SIZE]

[SIZE=+1]

http://www.cindyvallar.com/granuaile.html

I'm afraid most of the stuff currently published on Grainne Ní Mháille is either not born out by the historical evidence or has been so 're-interpreted' according to either the nationalist or feminist traditions and therefore so far removed from its original context as to be meaningless. A typical example of this would be the whole 'Bald Gráinne' myth. It is far more likely that her name Granuaille was derived from her place of birth - Gráinne of Umhall. This is given weight when we consider she was the 2nd recorded Grainuaille among the Uí Máille of Umhall - it is unlikely the same family would produce two bald Gráinne's.

Nor is there any evidence she actually met Elizabeth I - the State Papers record her as being at Court in 1593 and 1595 - this does not mean she actually met the Queen herself.

As is often the case with romanticised tales such as the ones about Gráinne - the truth as evidenced by the State Papers and various private letters just coming to light is far more interesting.

More accurate info can be found at:

http://www.historyireland.com///volumes/volume13/issue2/features/?id=113811

or in a TG4 documentary entitled Sa tóir ar Ghrainuaile which they seem to show quite often.0 -

Anyone got information on smuggling on the east coast? I know Rush in North Co Dublin was at the heart of a successful smuggling operation between Ireland and Scotland via the Isle of Man.0

-

Corsendonk wrote: »Anyone got information on smuggling on the east coast? I know Rush in North Co Dublin was at the heart of a successful smuggling operation between Ireland and Scotland via the Isle of Man.

Go back to posts 17 to 21 or so and there is some info.0 -

Smuggling on the Irish Sea

Extract from the Atholi Papers, papers of the Lords of the Isle of ManReply from Dublin re smuggling from Isle of Man, 1764]

May it please your Lordships

In obedience to your Lordships commands signified by Mr Whately's letter of the 11th day of May last, we have made strict enquiry into the smuggling trade carried on between the Isle of Man and this Kingdom. The result whereof we are now to report to your Lordships.

It is un-necessary to describe to your Lordships the situation of the Isle of Man, futher than to observe that it is near enough to this Kingdom to answer all the smugglers purposes, enabling them to keep up a constant and speedy intelligence, allowing them by the shortness of the passage to execute their schemes at the precise times which their associates have to apprize them of, and to take all advantages of wind and weather.

This situation, and the circumstances of the Government of the Isle of Man, afford a refuge to bankrupts, fugitives from this Kingdom, who resort there in such numbers as to make a considerable part of the inhabitants of the Island. Many of these men have established a correspondence here, who having been in trade and knowing exactly the extent of the Irish Laws, are prepared to manage their contraband traffic with advantage, and frequently to baffle the endeavours of the Revenue Officers appointed to guard the coast of this Kingdom.

The contraband trade from the Isle of Man is carried on almost entirely by Wherries built at Rush, a fishing town within sixteen miles of this city; they are prime sailors, and several of them have at late been purchased by the Isle of man smugglers for the purpose of running goods on the coast of Scotland. Within a few years they have increased the dimensions of their wherries, that although they are quite open boats, they have sailed round the north coast, and have landed their cargoes in the most western parts of this Kingdom.

All possible care hath been taken here to destroy this pernicious trade, as far as the power of the legislature of this Kingdom can extend. No boat can sail to the Isle of man from the coast between Wexford and Londonderry without first taking out a permit, by which means notice is given of the sailing of each smuggling wherry. All vessels with exciseable goods from that Island belonging to any port or person residing in this Kingdom are forfeited with their cargoes, if discovered to be within three leagues of the Irish shore ; And all contracts with the Isle of man for exciseable goods are declared void. as occasion pointed out we have tried variety of expedients; We have as far as prudence allows, gone to a great expence in establishing cruizing barges at sea, and guards upon the shores, which have been of considerable service, and although they have not put a stop to the smuggling from that Island, yet they have checked it considerably, and prevented an encrease of it.

We are satisfied that the revenues of this Kingdom do suffer very considerably by the smuggling from the Isle of man, but to what amount it is impossible for us to ascertain. The value of the goods from thence. seized on this coast, generally amounts one year with another to about ten thousand pounds.

Another branch of the smuggling trade is by vessels from the coast of Cumberland and Lancashire touching at the Isle of man. This is carried on for the most part by the Whitehaven colliers, and consists chiefly in small adventures bought by the sailors; But as good care is taken to rummage the vessels, and to punish the offenders we believe the damage which the Crown sustains in this instance is inconsiderable.

We do not find that the practice of carrying debentured goods to the Isle of Man hat yet been set on foot in this Kingdom.

The goods imported into the Isle of Man in the greatest quantities, are coarse teas from Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway; brandy, wine and tobacco from France, rum from the West Indies; and debentured tobacco from Great Britain. Beside these, are imported there in smaller quantities, China silk, arrack and other East India goods, coffee, geneva and juniper berries. The Liverpool merchants also import from Holland to the Isle of Man and lodge in stores which they have provided there, gunpowder, fire arms, toys, and East India goods for their African trade.

This is the result of the best enquiries we have been able to make, which we humbly submit to your Lordships consideration, and are with the greatest respect

Your Lordship's most obedient and most humble servants

Jn Ponsonby

John Bourke

A Trevor

Ben Burton

Newtown

Custom House Dublin 20th October 17640 -

Advertisement

-

Extracts from

http://www.coastguardsofyesteryear.org/news.php

concerning smuggling at Loughshinny in North Co Dublin.To Comptroller General. Preventive Water Guard. Dublin.

27th.November 1821.

Sir, I beg to acquaint you that Mr.Harris, Chief Officer of the Preventive Station at Rush and six of his men being out on duty at Loughshinney in company with the Chief Boatman and five of the crew of the Station at Skerries on the night of the 23rd. at 9 pm. He discovered a smuggling cutter in the bay at 11pm. Burnt a blue light and fired three carbines as a signal for the remainder of the Rush and Skerries crew to join him. At midnight upwards of 300 men, armed with muskets, pistols, pikes and pitchforks came down for the purpose of forcing a landing. At 2 am. the fieldpiece was brought to Loughshinney from Skerries by Lt. Smith, Chief Officer and a party of men when the smugglers dispersed in all directions at 3am.

Two large boats apparently laden put off from the cutter and came close to the shore but finding all the smugglers and cars had left the beach they immediately returned on board and after unloading the boats they got underweigh and put to sea.

Richard Williams, Commissioned Boatman and Henry Gilmore, an extra man at the Preventive Station, Rush, were surrounded and disarmed by nearly 100 men on Rogerstown Strand at 9pm. And it appears to have been the intention of the smugglers to disarm both the Rush and Loughshinney crews. Thomas Randal, Chief Boatman at Skerries was knocked down and disarmed at Kirkeen Cross, near Loughshinney. The smugglers I am informed succeeded in landing some tobacco but I believe a very small quantity.

As they appeared determined to force a landing if possible, I beg leave to recommend that 8 additional extra men may be employed in this district, viz. 3 at Skerries, 3 at Rush and 2 at Portrane.

(signed) Thomas Blake.Custom House Dublin 11th.December 1821

Sir. I am directed to inform you for the information of the Lord Lieutenant that it appears from the report of Captain Christian that one of the Water Guard named Michael Griffin was taken prisoner and confined in a house at Loughshinney, as were also Williams and Gilmore the detatched men alluded to in Mr.Blakes report, that the Chief Boatman at Skerries was also sent prisoner to the same house by the Smugglers and his arms taken from him when the Water Guard were attacked by two or three hundred armed men, yet so far were the main body of the Water Guard from allowing themselves to be surrounded, that they forced their way through the mass, one man fired at a Smuggler who made a thrust of a bayonet at him, and another if the Water Guard men wounded a Smuggler with his Bayonet, that the Water Guard did not evince any want of courage, but having left Loughshinney to join a reinforcement expected from Skerries. A small landing was effected during their absence but that on their return they prevented further landing from the Smugglers boats and the Parties on shore with their empty cars and horses dispersed.

I have the honor to be Sir your most obedient Humble Servant. C.J.Allen Maclean.

To The Rt. Hon.Charles Grant.0 -

The slave ship Amity that sank off Courtmacsherry in 1701

The only survivor was a black slave boy.Planks from the Amity

Amity planks

In December 1701 Dunworley (a few miles from Courtmacsherry) received a surprise visit from a slave ship of the Royal African Company. The ship was named The Amity and was bound for London having departed the Guinea coast in Africa. The Amity was heavily laden with ivory and camm-wood (a red hardwood from the African Padauk tree.) A beam of camm-wood stills serves the role of lintel in supporting a chimney-beast in a local cottage. However, destiny had other plans for the unsuspecting Amity. A series of Atlantic storms blew the ship hopelessly off course and onto a submerged reef in Dunworley Bay. In no time the ship was pounded to pieces on the rocks and its cargo scattered in all directions. All hands were drowned save a black slave boy who somehow made it ashore under ferocious conditions. Folklore gleaned from the late Donal Hegarty of Lehina near Dunworley tells us that the following morning Dunworley’s beach was littered with dead bodies, some were Africans, the remainder were white-skinned.

We do not know how many lost their lives on that fateful night but we can assume around fifty people including captain Phaxton, the average slave-ship engaged a fifty-man crew to work their vessels, Donal Hegarty’s lore gives us an insight into the sectarian attitudes of the day. The African corpses on Dunworley Strand were presumed to be heathens and therefore buried in shallow graves in the sands where they lay. However, white skinned corpses were presumed to be Christians and carted off to be buried in hallowed ground. The broken remains of the Amity were reported to be in two fathoms of water, which no doubt facilitated the recovery of much of her cargo over the following months. The RAC took active steps to recover their goods from the sunken ship. They engaged local man Robert Travers, and two others, Morgan Bernard, and Peter Renue a Cork merchant. Further accounts of the welfare of the slave boy fade from the record. Unfortunately, all correspondence from Travers to the RAC appears to have been lost. The slave boy does not appear to have made it back to London. Did he die of pneumonia as a result of his long immersion in the storm-tossed Atlantic on that fateful night in December 1701? Could he have died as a result of injuries inflicted on him when his ship broke up on the foaming reef? We do not know! Brief snippets from the original RAC letters to Travers suggest that he was somebody of importance to them. On 23 December 1701 the RAC wrote a letter to Peter Renue urging him to:

We require you to take care of the negroe salved from out of the ship and take such attentions as are for our service, let him be supplied with warm clothes and other necessaries and send him to us by the first ship bound for the river Thames