Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

IRISH COWBOYS & SOLDIERS

Options

Comments

-

Here is a story from CNN of foul play and a mass gravein in Pennsylvania

</H1><H1>Grandfather's ghost story leads to mysterious mass grave

By Meghan Rafferty, CNN

August 24, 2010 -- Updated 2128 GMT (0528 HKT)

Mass murder in 1832? Maybe

STORY HIGHLIGHTS- Former railroad worker told ghost story every Thanksgiving

- He left a box of documents to one of his grandsons

- Brothers followed clues, discovered mass grave in Philadelphia suburb

- Experts are checking remains for signs of foul play

Malvern, Pennsylvania (CNN) -- "This is a mass grave," Bill Watson said as he led the way through the thick Pennsylvania woods in a suburb about 30 miles from Philadelphia.

"Duffy's Cut," as it's now called, is a short walk from a suburban cul-de-sac in Malvern, an affluent town off the fabled Main Line. Twin brothers Bill and Frank Watson believe 57 Irish immigrants met violent deaths there after a cholera epidemic struck in 1832.

They suspect foul play.

"This is a murder mystery from 178 years ago, and it's finally coming to the light of day," Frank Watson said.

The brothers first heard about Duffy's Cut from their grandfather, a railroad worker, who told the ghost story to his family every Thanksgiving. According to local legend, memorialized in a file kept by the Pennsylvania Railroad, a man walking home from a tavern reported seeing blue and green ghosts dancing in the mist on a warm September night in 1909.

"I saw with my own eyes, the ghosts of the Irishmen who died with the cholera a month ago, a-dancing around the big trench where they were buried; it's true, mister, it was awful," the documents quote the unnamed man as saying. "Why, they looked as if they were a kind of green and blue fire and they were a-hopping and bobbing on their graves... I had heard the Irishmen were haunting the place because they were buried without the benefit of clergy."

When Frank inherited the file of his grandfather's old railroad papers, the brothers began to believe the ghost stories were real. They suspected that the files contained clues to the location of a mass grave.

"One of the pieces of correspondence in this file told us 'X marks the spot,'" said Frank. He added that the document suggested that the men "were buried where they were making the fill, which is the original railroad bridge."

for more on this and a news video check out this link

http://edition.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/08/24/pennsylvania.graves.mystery/#fbid=5P5fiAVf2gQ&wom=false0 -

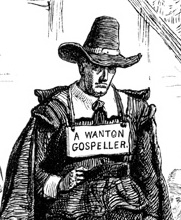

Two Irish Papists caught doing Burglary in Canada ”Early American Criminals: The Canadian Burglars

Early American Criminals: The Canadian Burglars [7:32m]: Hide Player | Play in Popup | Download (7179)

Early American Criminals: The Canadian Burglars [7:32m]: Hide Player | Play in Popup | Download (7179)

On Friday, December 4, 1789, William Mooney Fitzgerald and John Clark were scheduled to appear before the court in St. John, New Brunswick. They were to learn their sentence after being tried and found guilty of burglary the day before. That morning, Rev. Charles William Milton entered their prison cell and later wrote that he found “two unhappy men, surrounded with chains, expecting every moment to have sentence of death pronounced on them,” which “together with the disagreeable stench which arose from them, so affected me, that I was speechless for some time.”

After meeting Fitzgerald and Clark, Milton accompanied the two convicts to the court, where at noon the Honorable Judge Upham pronounced a sentence of death on them and ordered that they be held in jail until their execution on December 18.

The Head of the White Boys

William Mooney Fitzgerald was born in June 1763 in the city of Limerick, Ireland. His parents were honest and creditable, but at the age of sixteen he joined the White Boy gang and became their leader.

The White Boys were a band of agrarian Irish-Catholic insurgents who committed violent offences starting around 1759 to protest enclosures of common land, evictions from rented land, and exorbitant tithes. They took their name from the white smocks they wore as uniforms, and they were accused of carrying out “dreadful barbarities” on people who did not follow their orders or join their gang:they cut out their tongues, amputated their noses or ears; they made them ride many miles in the night on horseback, naked or bare-backed; they buried them naked in graves lined with furze [a thorny bush with yellow flowers] up to their chins; they plundered and often burned houses; they houghed [i.e., cut the hamstring] and maimed cattle; they seized arms, and horses, which they rode about the country, and levied money, at times even in the day (Sir Richard Musgrave, Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland, From the Arrival of the English, 1802).During the first half of the 1780’s when Fitzgerald headed the gang, White Boy activity seemed to focus on protesting tithe collections, although the institution in general had already begun to decline by this time.

While a member of the White Boys, Fitzgerald carried out several capital crimes. At the age of 19 he was condemned to death for committing rape, but for some reason was pardoned. In 1785 at the age of 22, he and six others broke into the home of Rev. Buckner and stole an astonishing 15,000 guineas without being detected. Justice finally caught up with Fitzgerald when that same year he was caught and sentenced to death under the White Boy Act, but he was reprieved on condition of being transported to Botany Bay.

Fitzgerald boarded a ship with 138 other convicts, but instead of proceeding down the coast of Africa and west towards Australia, the captain headed in the opposite direction. He sailed towards Nova Scotia with the intention of selling the convicts as indentured servants. The captain’s scheme was easily discovered, so he dumped his shipload of convicts near Little River in Massachusetts (which later became part of the state of Maine).

Fitzgerald committed two thefts while in Massachusetts before fleeing to St. John in New Brunswick, where he met up with some of his fellow convicts from the ship. They committed several thefts together before Fitzgerald and Clark teamed up and were arrested for the burglary of William Knutten’s house.

An Unusual Pardon

John Clark was also born in Ireland around the same time as Fitzgerald. After displeasing his father through his conduct and actions, Clark joined the army, but then deserted it and became a thief. He rejoined the army, but before he could desert again, he was shipped off to America to fight in the American Revolution. Clark was discharged after the war, but he re-enlisted in another regiment, only to be discharged again after being tried by court martial for thefts and misdemeanors.

In 1786, Clark and two others were tried and sentenced to death for burglary in Halifax. But Clark received a pardon on condition that he carry out the execution of the two other burglars, which he did with their consent. Despite this near miss, Clark continued to commit even more thefts in Nova Scotia.

On October 18, 1788, Clark traveled to St. John, where he met one of the women from Fitzgerald’s convict ship. She and another woman convinced Clark to carry out with Fitzgerald the burglary that led to their arrest.

Regular Visits in Prison

As Fitzgerald and Clark came out of the court room after their sentencing, Rev. Milton handed them a Bible. He later discovered that Fitzgerald not only was brought up as a “rigid papist,” but that he was illiterate, so Clark volunteered to read to his partner. Milton visited the two prisoners every day to discuss the Gospel. On the fourth day, Milton was advised to limit his visits so as to avoid offending the public, but after some reflection he “without hesitation, rejected the advice, as coming from the father of lies.”

On the Sunday before their execution at three o’clock in the afternoon, Milton preached in front of the jail. The convicts stood on a snow bank and Clark on top of a table, and despite the extreme cold, a large group of people turned out to hear his sermon and gawk at the prisoners. Before Milton began his speech, Clark asked permission to read a confession to the public, which was granted. Many tears were shed during the sermon, and afterward the “prisoners appeared very much resigned.”

On Wednesday, the judge ordered Fitzgerald and Clark to hear their death warrant read aloud, and by their own request their coffins were delivered into their jail cell. Milton wrote that the sight of them lying in their coffins was one “which no feeling mind could behold without being affected.”

While in prison, Fitzgerald supplied to the authorities a list of seventeen convicts he knew from the ship that transported him, along with their crimes. Eight of the convicts were transported for shoplifting or theft, and four committed animal theft. Others were banished for highway robbery, coining, and rape.

Milton’s regular visits must have had their effect, because on the day of their execution he found Fitzgerald and Clark “as much composed as if they were about going a pleasant journey.” The two walked to their place of execution on each side of the Reverend, who took leave of them after they ascended the ladder of the gallows. While moving up the rungs, Milton heard Clark observe that “every step he took was a step nearer to God.”

The two were executed at half past noon. “More solemnity,” Milton wrote, “was perhaps never observed at any execution before.

http://www.earlyamericancrime.com/criminals/canadian-burglars0 -

Don't forget that when you go into the shrine in the Alamo, there's an Irish tricolour there too.

Irish people have historically gone poncing around the world and ended up fighting in other people's wars. I'd occasionally fly a small tricolour behind my hatch in the tank in Iraq, I'd meet all sorts of other emigrants in the turrets of other vehicles passing by.

NTM0 -

It was almost 180 years folllowing their execution before Dominic Daley & James Halligan were exonerated by Michael Dukakis .

Boston of 1806 was not a friendly place for the Irish as this story points out. The case became a cause celebre for almost 2 centuries.

This was pre-famine emigration and just 8 years after Vinegar Hill in 1798 and 3 years following Robert Emmetts execution.June 5th 2008 was the 202nd anniversary of the hanging deaths of Dominic Daley and James Halligan. I was privileged to attend this event and was asked to place flowers at the base of their memorial stone. They were two Irish Immigrants to Massachusetts who were accused of murder. The atmosphere in Massachusetts at that time was anti-Irish and anti-Papist. On that day 25,000 people gathered in Northampton to witness the double hangings. Their bodies were taken down from the gallows and dissected and their bones strewn in the woods unburied...as was the punishment in those days for heinous crimes. Ten years later a local farmer was said to have confessed to the murder on his death bed.

I researched this true story and in 1984 my play "THEY'RE IRISH! THEY'RE CATHOLIC!! THEY'RE GUILTY!!!" was presented for the first time to pressure Governor Michael Dukakis into granting them posthumous Exonerations This was successful and the pardon was granted to them on March 16, 1984

http://blog.jim-curran.com/2008/06/06/dominic-daley-and-james-halligan-memorial-service.aspx.Dominic Daley and James Halligan Trial:

1806

Defendants: Dominic Daley, James Halligan

Crime: Murder

Chief Defense Lawyers: Francis Blake, Thomas Gould, Edward Upham, Jabez Urham

Chief Prosecutors: James Sullivan, John Hooker

Judges: Theodore Sedgwick, Samuel Sewall

Place: Northampton, Massachusetts

Date of Trial: April 24, 1806

Verdict: Guilty

Sentence: Death by hanging

SIGNIFICANCE: This otherwise obscure trial—rightly or wrongly—later came to be seen as epitomizing the anti-Irish bias that was widespread in New England during the early nineteenth century.

As the new American republic moved into the nineteenth century, most New Englanders were still of British stock and Protestant persuasion. Many of these Americans made no secret of their detestation of all Roman Catholics. Most especially, although they had just finished a war to break away from Great Britain, many New Englanders kept alive their English relatives' deep-seated prejudice against the Irish. It is against this background that an otherwise routine trial in a corner of Massachusetts has come to be judged by later generations.

The Crime

It was on November 10, 1805, that the body of a young man—his head bludgeoned and with a bullet hole in his chest—was discovered in a stream near Springfield, Massachusetts, after his horse had been found wandering in a nearby field on the afternoon of November 9. Two pistols were found near the scene of the murder. Letters in the horse's saddlebags identified the victim as Marcus Lyon, who turned out to be a young farmer from Connecticut making his way home from upstate New York.

Several local men and a young boy quickly came forward with reports of two strangers seen walking along the turnpike in that vicinity on November 9. On Monday, November 11, a sheriff's posse set out and, by asking everywhere along the road, were able to catch up on Tuesday with two such men in Cobscrossing, Connecticut (near Rye, New York). They were Dominic Daley and James Halligan, two fairly recent Irish immigrants, and they admitted that they had come along that turnpike while walking from Boston en route to New York City. Although both men denied having any knowledge of the murder, they were arrested and brought back to Massachusetts to await trial. For some reason, Daley was singled out as having performed the actual act of murder while Halligan was accused of "aiding and abetting."

The Trial

On Thursday, April 24, 1806, the courtroom in Northampton, a county seat in western Massachusetts, was so packed that the trial was moved to the town's meeting house. Each defendant had been assigned two lawyers, but they had been given barely 48 hours to prepare a defense. The presiding judges were two of the most distinguished jurists in Massachusetts; a jury of 12 had been agreed upon. In the weeks before the trial, rumors had surfaced throughout the region promising that there would be no end of evidence linking these two to the murder. But in the end, the prosecution's case rested for the most part on a series of witnesses who could at best claim they recognized one or both of the defendants as having been walking along the turnpike near the murder scene on November 9.

There was also a gun dealer from Boston who testified that he had sold two pistols like the presumed murder weapons to a man who "talked like an Irishman"; otherwise he could not identify either of the two defendants as the purchaser. The owner of the inn where Lyon had spent some months in upstate New York testified that Lyon, the night before he had set out on his journey, had shown him some banknotes, two of which were exactly like those found on the person of Daley. Although the judge would instruct the jury to regard the testimony about the guns and the money as "circumstances too remote to bear upon the present case," the fact is the jury had been allowed to hear this. A 13-year-old boy, Laertes Fuller, gave the most damaging testimony. He alone connected the two men to the very locale of the murder and to the horse at about midday on November 9, although even he did not claim to have had a good look at Halligan.

When the prosecution rested its case, Daley and Halligan's lawyers offered no witnesses and the defendants, due to the law then in effect in Massachusetts, could not take the stand. Instead, one of Daley's lawyers, Francis Blake, delivered a long speech attacking the prosecution's case. Occasionally legalistic, sometimes eloquent, occasionally irrelevant, sometimes right-on point, Blake proceeded to argue that in fact there was no proof that Lyon had even been murdered on November 9, the day that Daley and Halligan were said to have been walking along that stretch of highway. The pistols were two of thousands in use at that time. (He said nothing about the banknotes, and the prosecution itself chose to drop that testimony—possibly because it appeared too "neat" to be true.) The case effectively rested on the testimony of the 13-year-old boy. Blake argued that the murder could not possibly have taken place during the brief 15 minutes when the boy said he first saw the two men on foot and then with the horse—during which brief period, moreover, the boy said he heard no gunshot.

No, said Blake, the real reason these two men were being charged was because they were Irishmen. After referring to the Boston gun dealer's identification as that of a "mind infected, in common with others, with that national prejudice which would lead him to prejudge the prisoners because they are Irishmen," Blake rose to even more rhetorical heights:Pronounce then a verdict against them! Condemn them to a gibbet! Hold out an awful warning of the wretched fugitives from that oppressed and persecuted nation! … That the name of an Irishman is, among us, but another name for a robber and an assassin; that everyman's hand is lifted against him; that when a crime of unexampled atrocity is perpetrated among us, we look around for an Irishman.But it was to no avail. The trial ended about 11 that evening, and the jurors returned with their verdict about midnight. Both men were found guilty, and the next day they were sentenced to hang.

An Execution and an Exoneration

In the days before their execution, the Reverend Jean Louis Cheverus, a Roman Catholic priest, came out from Boston and heard their confession. The two were hanged before a crowd estimated as 15,000 on June 5, 1806. Father Cheverus explained to the many Protestant questioners that "the doctrine of the Church" forbade him ever to reveal what the men had confessed. Inevitably rumors about this crime continued to surface but it was not until 1879 that there first appeared in print the claim that a man had confessed on his deathbed to being the true murderer. In later years, this claim was enhanced by such details as the confessor's having been the uncle of the young Laertes Fuller. But there was no corroborating evidence for either the confession or the uncle's ties to the crime, and eventually most people of western Massachusetts forgot about Daley and Halligan. However, as the Irish-American community became both more integrated and confident, individuals eventually succeeded in gaining a reconsideration of the case, and in March 1984 Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis proclaimed the innocence of Daley and Halligan.

The Issue of Bias

The now-accepted version is that Daley and Halligan were totally innocent and were persecuted only because of their being Irish and Catholic. But has this been proven? There is no denying that Roman Catholics in general, and Irish immigrants in particular, had to endure great discrimination and injustices at the time of the trial. Most people would agree that the case against Daley and Halligan was weak, even unacceptable by today's standards. In those days, there were no tests for fingerprints, ballistics, "crime scene," or other investigations for evidence. But still unclear to some is whether Daley and Halligan were found guilty solely because of their ethnic and religious ties. In fact, they were the men seen traveling along that road, and the posse that set out after them had no notion that they were Irish Catholics. The only overt reference to their being Irish on the part of the prosecution was the Boston gundealer's allusion to the speech. Nothing else said by the prosecution or judges referred to their being Irish or Catholics.

The issue of their guilt by dint of being Irish, in fact, seems to have been raised—and exploited—entirely by the defense lawyer. Daley and Halligan may well have been innocent, but the claim that they were convicted solely because of their being Irish Catholics seems unproved—and probably forever unprovable.

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3498200042.html0 -

Here is a bit more on the origans of the Irish in New England, cowboys were Irish - whats more they were first organised by a puritan who recognised their abilities.Irish Cowboys and Hobby HorsesYoung John Pynchon had inherited his father’s knack for details and organization. Furthermore he had Peter Swank’s knowledge regarding the buccaneer feed lot operation. Yet both men realized this new venture was going to call for a specialized type of labor force. Pynchon had an inspiration.

He recruited Irish cowboys.

Though often overlooked in history books, there were many Irish emigrants in New England by the mid-seventeenth century. Some had arrived as indentured servants. Others had fled Ireland of their own free will, willing to risk life and limb in an often savage new world, rather than live under the ruthless dictatorship inflicted on their homeland by the English conqueror Oliver Cromwell.

These Irish emigrants arrived with not only an ancient equestrian history but even brought a well-known Irish word with them. Their country had already been a center for beef and dairy production for more than five hundred years. As early as 1,000 AD Irish minstrels were recording songs about “the cowboy.” Medieval poems such as “The Triads” spoke of Irish men rounding up cattle from horseback. The Irish horse was as famous as the men who rode it. These natural pacers, imported into England as early as 1350, were favored mounts of squires, merchants and other gentry. The solid little Irish horse had a gait “as comfortable as a rocking chair on the hob.” The warm, flat area in front of the fireplace known as the hob was the most restful place in the house. The legend of the gently rocking “hobby horse” thus arose from this Irish pacer.

By the fall of 1654 John Pynchon and Peter Swank knew where they could find horses and the men to ride them for America’s first roundup.The Puritan RoundupAmong the Irish cow punchers Pynchon recruited was John Daley. In addition he purchased an indentured Scottish prisoner of war named John Stewart who became the resident blacksmith.

With his cowhands lined up, John Pynchon, America’s first cattle baron, was almost ready.

Like all ranch hands, first they needed horses.

When the Puritans arrived in America, they had originally been weak horsemen. A widespread belief was that horses were a luxury “belonging to the gentry.” Cattle, pigs and sheep had more uses to these sturdy yeomen. Not only could these animals be eaten, they provided essential by-products such as milk, hides, butter, etc. But the horse had little value after its death. English heritage had a strong bias against using horseflesh for human food. An exception to this was the winter of 1610 when the Jamestown colonists ate their seven horses rather than starve. It is not surprising then to discover the fleet that brought the Puritans to Salem in 1628 for example carried 110 cattle but only thirteen horses. The need for pack ponies and dependable riding mounts was soon evident. By 1640 there were an estimated 200 horses in New England, with more arriving on every ship. Many of these were Irish “hobbies.”

In 1647 the number of horses in Massachusetts had increased so quickly that the General Court passed a branding law. All animals were doubly branded: first with the symbol of the township in which it was located and secondly with the registered brand of its owner.

The Puritan cowboys needed this equestrian advantage. It was routine practice to let cattle roam free on commonly owned ground. The small Devon and Durham cattle were anything but docile, maybe not longhorn mean but tough, spooky and belligerent. Once they mounted, Pynchon, Swank, Daley and the others started America’s first cattle round up during the fall of 1654. The cattle were brought in, branded and then herded into newly built corrals.

That winter the majority of Pynchon’s neighbors' cattle roamed through the woods and common meadows trying not to starve during the brutal New England storms. Meanwhile Pynchon’s Devon and Durham stock were being quietly tended in their corrals. Several sheds protected the cattle from the worst of the elements. Wheat straw and cornstalks strewn across the floor served as both bedding and a dietary supplement. Every day or two for the next five or six months the cowboys brought them dried corn-on-the-cob, cured hay, vegetable scraps from the family table and pulp from the cider mill.

By February the technique of the buccaneers had been proved a success. The cattle left to forage by his neighbors were rail-thin and as wild as hawks. Pynchon’s stall-fed cattle were plump, gentle and friendly.

Old Fort Pynchon was where the first cattle-drive began in 1655.“Head ‘Em Up – Move ‘Em Out !”On a crisp spring morning in 1655 John Pynchon looked at the crew of mounted men waiting before him. There were no artists present to record the rig these cowboys wore. Like the Texans who rode a cow trail hundreds of years later, they must have dressed functionally in durable work clothes. Jackets and vests stitched from moose-hide or deerskins were common Puritan garments. Homespun shirts, buckskin breeches, fur caps and leather boots shiny with bear grease would have graced many a young rider. During the three week trip ahead of them, heavy dark wool capes would keep them warm during the day and serve as blankets at night.

One other thing they shared with the cowboys yet to be born. Though they came from diverse backgrounds and different countries, though some were slaves, some indentured servants, some free men, they all shared a common love of adventure and horses. They were America’s first cowboys about to ride into history.

John Pynchon gave the signal to “head ‘em up ..... move ‘em out.” His cowhands swung into action and the herd of stall-fattened Devon and Durham cattle began moving down the Old Bay Path from Springfield, Connecticut towards distant Boston, Massachusetts.

At first the deep grass-covered valley where they lived presented little problem. The rocky countryside between Springfield and Boston was soon in evidence though. The chuck wagon would not be invented by Charles Goodnight for a couple more centuries. The trail was too thin to allow wheeled traffic anyway. Pynchon probably solved the problem of feeding his cow hands by packing supplies along on a string of pack ponies.

Once they swung into the saddle we lose track of them. They ride into the sunset like an ancient equestrian puzzle.

No one has ever solved the record of their daily progress. The local Native Americans, Nipmucks, Nonotucks and Agawams left them alone. Many of the daily events encountered by America’s first cowboys may be locked away in a three hundred year old document A series of records kept by Pynchon - in a system of shorthand he invented - has never been deciphered.

Could the details of North America's first cattle-drive, an event which included Irish cowboys and African-Americans, be hidden in John Pynchon's still undeciphered records? It is known that the herd arrived at Boston Common almost a month later, mostly intact, and yielded Pynchon a handsome profit. This was the first long drive on record of fat-cattle to a city market anywhere in the present boundaries of the United States.

While we may lack the daily details of what those early cowboys did on the cattle drive, we do know that things were never the same in old New England.

In 1675 John Pynchon led his horsemen into battle during King Philip’s War. Several of them made daredevil style rides, delivering messages as heroically as any Pony Express rider. By 1700 the horse trade between New England and the Caribbean was so important that sailing ships were designed with built-in deck pens to hold 150 to 200 horses. These small ships took the Scottish nickname “jockeys.”

By 1750 cattle drives of more than two thousand horses and cattle, guarded by whip cracking cowboys, were a common sight along the cart roads connecting Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia and Boston. These drives created the first through roads linking the northern and southern colonies.

Finally, by the time of the Revolutionary War in 1776, the term “cowboy” was commonly used from Maine to Georgia to describe illiterate roughnecks herding cattle in the back country. It grew to have such a derogatory reputation that cattle herdsmen in the East adopted the English term drover instead. The word cowboy would not be popular for a hundred more years, out in some obscure little place called Texas.

The full article

http://www.lrgaf.org/articles/irish-cowboys.htm0 -

Advertisement

-

He claimed he killed 42 Victims and here is a link to the quiz.

I think he was called the Omaha Sniper.

http://quiz.thefullwiki.org/Frank_CarterQuestion 1: At the beginning of February 1926 a mechanic was murdered with a ________ pistol with a silencer attached..22 Long.22 Short.45 ACP.22 Long Rifle

[report]

Question 2: Soon after a doctor was murdered, and then a railroad detective was shot six times in neighboring ________.Mills County, IowaHarrison County, IowaCouncil Bluffs, IowaPottawattamie County, Iowa

[report]

Question 3: He was executed by electrocution on June 24, 1927 at the Nebraska State Penitentiary in ________.Omaha, NebraskaNorth Platte, NebraskaLincoln, NebraskaFremont, Nebraska

[report]

Question 4: Frank Carter (1881 – 1927) was a notorious sniper murderer in ________.Omaha, NebraskaOmaha – Council Bluffs metropolitan areaBellevue, NebraskaDouglas County, Nebraska

[report]

Question 5: [3] Other crimes included shooting indiscriminately into a ________ drug store.Bemis Park Landmark Heritage DistrictDowntown OmahaOmaha, NebraskaOld Market (Omaha, Nebraska)

[report]

Question 6: Carter was born in ________ as Patrick Murphy.County WexfordCounty GalwayCounty MayoCounty Kilkenny

[report]

Question 7: After a month-long trial where Carter's lawyers plead ________,[9]Bipolar disorderInsanity defenseInsanityMental disorder

This could be fun.0 -

Funnily enough Mayo does not celebrate their famous son.Frank Carter Born 1881 (1881)

County Mayo, Ireland Died June 24, 1927 (1927-06-25)

Lincoln, Nebraska Alias(es) Patrick Murphy Conviction(s) Two counts, First degree murder Penalty Execution Status dead Frank Carter (1881 – 1927) was a notorious sniper murderer in Omaha, Nebraska. Tried for two murders, Carter claimed to have murdered forty-three victims. He was known as the Omaha Sniper, Phantom Sniper, and the Sniper Bandit.

Crimes

Carter was born in County Mayo, Ireland as Patrick Murphy. At the beginning of February 1926 a mechanic was murdered with a .22 caliber pistol with a silencer attached. Soon after a doctor was murdered, and then a railroad detective was shot six times in neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa.[1] On February 15 Omaha's newspapers recommended the city blackout all lights after an expose on previous murders showed the victims were standing in their windows at home when they were shot.[2] During daylight hours, the sniper shot another in the face and fired through more than a dozen lighted windows. Businesses in Omaha came to a standstill, streets emptied and the city's entertainment venues emptied for more than a week.[3] Other crimes included shooting indiscriminately into a Downtown Omaha drug store.[4][5]

More than two weeks after his first murder Carter was captured in Iowa, 30 miles south of Council Bluffs at Bartlett in Fremont County, Iowa. After readily admitting his crimes,[6] he was convicted on two charges of murder, one for killing mechanic William McDevitt and the other for killing Dr. A.D. Searles.[7] After his conviction Carter admitted to being a parole breaker. He was released from the Iowa State Penitentiary in 1925 after serving time for killing cattle.[8]

After a month-long trial where Carter's lawyers plead insanity,[9] Carter was found guilty. He was executed by electrocution on June 24, 1927 at the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln, Nebraska. Carter was quoted as saying, "Let the juice flow" just before he died

http://www.ask.com/wiki/Frank_Carter The last executed prisoner to be buried here was Frank Carter, #9277, a notorious sniper serial killer who committed his murders in Omaha, Nebraska. He was also known as the Omaha Sniper, Phantom Sniper, and Sniper Bandit. He claimed to have murdered 43 people. He was born Patrick Murphy in County Mayo, Ireland in 1881 and started his killing spree in February 1926. He used the aliases of F. Louis Clark, Frank Louis, and Frank Wilson. Just by calling up his name on the internet you can find an array of websites with information on Frank. Of particular interest are Wikipedia.org and http://www.serialkillerdatabase.net. He was featured in the New York Times and Time Magazine. When in the electric chair he is quoted as saying “Shoot the juice”.0

The last executed prisoner to be buried here was Frank Carter, #9277, a notorious sniper serial killer who committed his murders in Omaha, Nebraska. He was also known as the Omaha Sniper, Phantom Sniper, and Sniper Bandit. He claimed to have murdered 43 people. He was born Patrick Murphy in County Mayo, Ireland in 1881 and started his killing spree in February 1926. He used the aliases of F. Louis Clark, Frank Louis, and Frank Wilson. Just by calling up his name on the internet you can find an array of websites with information on Frank. Of particular interest are Wikipedia.org and http://www.serialkillerdatabase.net. He was featured in the New York Times and Time Magazine. When in the electric chair he is quoted as saying “Shoot the juice”.0 -

A relative of mine Ricard O'Sullivan Burke, Confederate Colonel in the American Civil War, have a book on him somewhere in the attic:

" Ricard (no 'h') O'Sullivan Burke was about 18 when he deserted from the Cork militia - ........ - went to New York, then Central and South America, then California (gold mining), then Chile (joined the cavalry), then back to New York just in time for the civil war. He enlisted in the union army and fought at Bull Run, Yorktown, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg, among other places, and was eventually discharged in 1865 with the rank of brevet colonel, "having gone through the war without a scratch". In his spare time, he organized the Fenian Brotherhood in the Army of the Potomac, preparing himself for peacetime, when he was sent to England to buy guns for the Irish Republican Brotherhood."

http://irishbiography.blogspot.com/2010/03/fenian-colonel-hapless-explorer.html

he also appears to have been a key figure in the IRB in his 30's and was involved in the " Fenian Dynamite Campaign"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenian_dynamite_campaign

Bit more on his role in the failed uprising in Waterford in 1867 here

Seems like the lad liked a fight!0 -

A relative of mine Ricard O'Sullivan Burke, Confederate Colonel in the American Civil War, have a book on him somewhere in the attic:

" Ricard (no 'h') O'Sullivan Burke was about 18 when he deserted from the Cork militia - ........ - went to New York, then Central and South America, then California (gold mining), then Chile (joined the cavalry), then back to New York just in time for the civil war. He enlisted in the union army and fought at Bull Run, Yorktown, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg, among other places, and was eventually discharged in 1865 with the rank of brevet colonel, "having gone through the war without a scratch". In his spare time, he organized the Fenian Brotherhood in the Army of the Potomac, preparing himself for peacetime, when he was sent to England to buy guns for the Irish Republican Brotherhood."

http://irishbiography.blogspot.com/2010/03/fenian-colonel-hapless-explorer.html

he also appears to have been a key figure in the IRB in his 30's and was involved in the " Fenian Dynamite Campaign"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenian_dynamite_campaign

Bit more on his role in the failed uprising in Waterford in 1867 here

Seems like the lad liked a fight!

Amazing. What a full life he lived!

Incidentally, he was not a Confederate Colonel. I think you may have upset him by writing that 0

0 -

-

Advertisement

-

-

The most dangerous man in the West was James J.Dolan born in Loughrea.Check the recently published 'The Lincoln County War'by Paul O'Brien.Then you'll also find out that the Governor of New Mexico was right in not pardoning Henry McCarty aka Billy the Kid recently.

...and there was that Jewish-Irish pistolero Chaim 'Jim' Levy...born in Dublin...he plugged a guy that disliked him because he was Irish,not Jewish...0 -

The most dangerous man in the West was James J.Dolan born in Loughrea.Check the recently published 'The Lincoln County War'by Paul O'Brien.Then you'll also find out that the Governor of New Mexico was right in not pardoning Henry McCarty aka Billy the Kid recently.

...and there was that Jewish-Irish pistolero Chaim 'Jim' Levy...born in Dublin...he plugged a guy that disliked him because he was Irish,not Jewish...

Welome to the history forum Caledone.

If there were ever two fellahs deservin of gittin biographied here it was these fellahs who bravely tackled low down yellah bellied scum( i am a bit biased) .......but lay it on me

Do you have any more detail or links to these Caledone.0 -

Check J* Grit 'tough Jews' for Jim....I like that bit about whether he was slurred as a 'son of Erin' or 'son of Aaron'...

whatever he reached.. he was both...just like Briscoe....

As for 'popular Jimmy Dolan' as Pat Garrett called him, he was one for the ages...won the 'Lincoln County War' hands down....quote from Billy 'I went to meet Mr Dolan,to meet as friends...'...the Kid was a soldier on the other side....they did meet Feb 18 1879 and agreed to a truce...later that night murder occurred....

Billy reneged and went running to Ben-Hur author Gov Lew.Wallace to shop Jimmy in return for immunity for murdering Lincoln sheriff Major William Brady of Co Cavan...O'Brien gives the real skinny in his recently published book...0 -

The Donnellys were bad neighbors...they also voted the Orange ticket...they were killed by fellow Irish, a kid visiting at the time of the murders hid under a bed and saw the action...nobody was convicted..A lot of Irish ended up in Canada.

One family the Donnelly's were involved in a feud which resulted in the massacre of 5 of them around 1880 by a local vigalte group.

There are a few versions of the story

http://www.donnellys.com/History.html

http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/notorious_murders/family/donnelly/1.html

http://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/donnellys/home/indexen.html0 -

-

old_aussie wrote: »Riley joined the stream of deserters

Is this an Irish military trait?

Riley left before the outbreak of hostilities which is why he was not

butchered with the other captives.General Harney did the job of mass hanging,including that of a double amputee POW.No wonder he was'nt given a command in the 'Civil' War.His CV included murdering his black housekeeper;the Army protected him from prosecution.

He had the doomed men stand in wagons with ropes around their necks while the battle raged until the Stars and Stripes was raised.Then the horses were flogged forward.The men gave a cheer which is misinterpreted as for the US flag;they were actually cheering the Mexican cadet who took the taken down Mexican flag and hurled himself from the battlements.Deserters they may have been but cowards they were not.

After that debacle the US Army introduced Catholic chaplains....0 -

-

Jesse may not have been Irish but how about gang member Whiskeyhead Ryan?

Got felled by a low branch while agallop...0 -

-

Advertisement

-

-

I can't imagine how I missed this and came across it on redditThe Irish Invasion of CanadaFrom Maine to Wisconsin, throughout the spring and summer of 1866, an estimated twenty-five thousand Union and Confederate veterans of the Civil War – members of the Fenian Brotherhood and calling themselves the Irish Republican Army -- gathered along the northern border of the newly-United States for the purpose of invading and capturing Canada.Leaders of the Fenian Factions

Col. John O'Mahoney

Col. John O'Mahoney William Roberts

William Roberts

Who and what were these Irish warriors and why were they intent on invading our neighbor to the north? Nicknamed the Fenians, the I.R.B. (Irish Republican Brotherhood) was the precursor of the 20th century I.R.A. It was first established in 1857 in the United States as a provisional government for an independent Ireland by two of the leaders of the Young Ireland uprising of 1848 who had escaped from English capture and found their way to New York City.

Here, two of the leaders of the Young Ireland uprising of 1848, John O’Mahoney and James Stephens, founded an Irish Republic in exile as they called it “to make Ireland an independent democratic republic of the Fianna.” In 1858, Stephens then returned to Ireland and formed an Irish branch of the Brotherhood.

The two branches of the I.R.B. were created specifically to train and equip a Celtic army capable of fighting and defeating the English. At the suggestion of O’Mahoney, who was a student of Irish history and mythology, the members of the I.R.B. were called “Fenians” after the legendary “Na Fianna” of ancient Ireland who were a band of mythological warriors that served as bodyguard to the “Ard Ri” – the Irish High King. While known as Fenians during the Civil War, the military arm of the Brotherhood which was to be established after the War, was to be known as the Irish Republican Army (the I.R.A.) the letters emblazoned on the buttons of their green Civil-War-style uniforms.

It has been reported that during the Civil War at least 14,000 Irish Yankees and an almost equal number of Irish Confederates were dues paying members of the I.R.B. -- and virtually all of the estimated 200,000 emigrant Irishmen who served in both the Union and Confederate Armies but hadn’t necessarily paid their $1.00 I.R.B. initiation fee or their 10 cents weekly dues – were sympathetic to the Fenian cause and shared the common bond as adherents of the Brotherhood.

To the north in Canada, there were reportedly another 125,000 I.R.B. members, most of whom were said to be ready to join the Republican Army when it was scheduled to be activated following the end of the Civil War. Whether they wore Union blue or Confederate gray -- whether from Boston or Baton Rouge — or County Tyrone or County Roscommon – just as did the Protestant Masons in both armies when they met on the battlefield during the Civil War, so also did both the Catholic and Protestant, Union and Confederate, Irish soldiers who considered themselves to be Fenian brothers in arms united in a common cause–-a cause so powerful it transcended both religious differences and a war for states’ rights or for a union of states. This may have been the reason why as legend has it the Irish flag of the 28th Mass. which was captured by Irish troops from Georgia at Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg, found its way back to the Yankee 28th the morning after the battle in some mysterious manner and it reposes today in the Massachusetts State House vault.

General Thomas Francis Meagher, who founded and commanded the Irish Brigade, was the earlier Irish war leader known as “Meagher of the Sword.” Together with Stephens and O’Mahoney, he was foremost among the Young Ireland army in the uprising in 1848 when 6,000 Irish men and boys armed with pitchforks, pikes, and hurling sticks battled British Regulars and lost. Most of their leaders who survived the battle, although first sentenced to be hanged, were exiled to a British penal colony in Australia from which Meagher escaped in 1852 and made his way to New York City. There he became a wealthy and influential lawyer and newspaper editor and one of the first supporters of the Brotherhood although not a member.

When civil war broke out, Meagher formed the 69th New York Volunteer Militia regiment to be the nucleus of an all-Irish Brigade. He was one of Lincoln’s many political Generals, given a star to insure the support of the Union cause by his followers. One of Meagher’s stated purposes in forming the unit was to establish an Irish Army of liberation by giving Irishmen formal military training and battle experience so they would be better able to fight the English.

However, Meagher himself did not join the I.R.B. until after he resigned his commission and left his beloved Brigade in May of 1863. Following the Battle of Chancellorsville, he was so disconsolate by the outrageous ruin and devastation his Irish soldiers had suffered since 1861 that he resigned because it had become, in his own words, “a poor vestige and relic of the Irish Brigade.”

With the end of the Civil War, the ranks of the Fenian Irish Republican Army swelled as discharged Irish soldiers from both North and South joined up to fight in the coming new war to free their mother country from the English oppressors. The Fenian leaders, many of whom were themselves veterans of the Civil War, were now in command of an estimated 25,000 Irish veterans from both Union and Confederate armies -- better trained and equipped to do battle than ever before in Irish history. These fighting men saw a unique opportunity to strike a mortal blow against the English government and, at long last, win freedom for their Celtic homeland after more than 200 years of British rule and oppression.

This time, unlike 1848, rather than staging an internal uprising in Ireland by a rag-tag youthful horde against a better-armed and trained English army, the Fenians could either use a steamship fleet of former Union warships to cross the Atlantic and land a battle-hardened army blooded by four years of war on the shores of Ireland to attack the occupying British forces -- or they could use their fleet to blockade Canadian ports while launching from the northern frontier of these now re-united States, a military invasion by well-armed and seasoned veterans against a relatively unprepared English garrison force and Canadian militia...and with the expectation of being joined by both Irish and French Canadians who wanted to throw off the British yoke.

Because of America’s smoldering hatred against the British government for their support of the Confederacy and their failure to pay reparations for the Union ships sunk and the men killed, yet mindful of appearing to adhere to international law, President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of War Stanton covertly supported the Irish efforts against the British. Surplus U. S. arms, equipment, and warships were readily made available to the Fenians and it was understood that the Johnson Administration would turn a blind eye to any violation of United States neutrality the I.R.B. might make.

In October of 1865, the Brotherhood held a Fenian Congress Convention in Philadelphia to determine their future course of action. The Convention endorsed a constitution, elected as first I.R.B. President Fenian founder John O’Mahoney ( a former Colonel in the 69th New York of the Irish Brigade), and set up various provisional government agencies including a Congress and a Cabinet. In New York City, a mansion in Union Square was acquired as a temporary capitol building to house the provisional Irish government and from its dome flew the flag of the harp and the sunburst...the same flag carried by the Irish Brigade in the Civil War.

As is usual with the Irish...especially Irish politicians, there was “a tendency to disunity and splits.” At the Convention, the I.R.B. split in two. One group under President O’Mahoney, wanted to launch a war against the English by landing on Ireland’s shores and attacking them on Irish soil. Obviously, such an invasion force would have to come from the American continent. It was felt it would be more politic if the Fenian forces used as an embarkation port an island in the Canadian Maritimes. At that time the Maritimes consisted of separate and independent British colonies which had not as yet joined the Canadian Confederation.

The other Irish faction, headed by former New York militia Colonel William Randall Roberts, called for an invasion of Canada to be launched from the northern U.S. border with the intent of taking over Canada and trading it back to England in exchange for the independence of Ireland. The two factions were so divided that Roberts, who had been elected Vice President under O’Mahoney, called a second Convention of his supporters at which he was elected President by his group of dissidents. Following that meeting, Roberts stated:

“The Irish Republic is yet ideal without a local habitation…. We must have some place for our government to raise a flag, build ships, issue letters of marque….England could surround Ireland with a cordon of ships of war, but if we had a country with sea ports, we could send our ships to prey on her commerce, run blockade runners to Ireland, and get nations to recognize our belligerency. If we haven’t a country our ships would be condemned as pirates…. With 50,000 men we can sweep John Bull into the sea. England has a lot of foes now. America is mad. What a chance!”

Roberts’ followers then endorsed his plan to invade and capture Canada the following year.

In November, 1865, Roberts met with President Andrew Johnson and received his support in that Roberts was assured the United States would “recognize the accomplished facts.” In other words, should the I.R.B. succeed in capturing Canada, the United States would recognize the new government as the Irish Republic in exile. Without objection either from General Grant or the War Department, Roberts named as his Secretary of War for the Irish government in exile, United States Army Major-General Fighting Tom Sweeney, an American citizen who was born in Cork and who stilled served on active duty in the United States Army.

O’Mahoney’s choice was F.F. Millen who had been a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Mexican Army’s Irish Legion of St. Patrick which had fought against the Americans during the Mexican War. Millen was sent to Ireland where he was to lay the groundwork for O’Mahoney’s planned invasion by leading a mutiny of the 8,000 Fenian soldiers then serving in the British Army of Occupation in Ireland and the 7,000 Fenians in the British militia. In the 1950s, 100-year old British secret files were opened which revealed that Millen was, in actuality, a British spy.

Evidently, on reaching Ireland, Millen alerted the British authorities to the plans of both Fenian factions. In expectation of a Fenian invasion of Canada taking place on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1866, (which, to Millen’s knowledge, had been the agreed upon invasion date originally decided before he left for Ireland), the British and Canadian authorities recruited 10,000 volunteers to patrol their Southern border. When the expected St. Patrick’s Day incursion failed to occur the volunteers were dispersed -- remaining on duty only until the 31st of March. About that same time, again in response to Millen’s warning and unknown to the Irish, a fleet of six British warships arrived off the Maritimes and began patrolling Canadian waters.

On the first week in April, 1866, IRB President, John O’Mahoney assumed the rank of General in his Irish Republican Army and began assembling a force of 1,000 men in Calais and Eastport, Maine. There, his army of Union and Confederate veterans waited for the arrival of their arms, ammunition, and accouterments coming from New York by steamship so they could invade Campabello Island off the Maine coast.

These war-surplus supplies were purchased from U.S. military inventories with the acquiescence of President Johnson and Secretary of War Stanton. Washington also felt that just as the English had disregarded neutrality laws during the Civil War and openly supplied arms and ammunition to the South, so too could the American government assist the Irish in their rebellion by overlooking the same neutrality laws so recently scorned by the British government.

Once his troops were armed and equipped, it was O’Mahoney’s intent to capture Campobello Island for use as the embarkation port from which the Fenian Army would cross the Atlantic and free Ireland. To keep up the pretense that there was no U.S. involvement with the Fenians, President Johnson sent General George Gordon Meade and about 20 artillerymen on an American warship to Eastport, Maine. Meade had been instructed to make a show of stopping the Fenian incursion by persuasion and without force of arms.

Meade’s persuasive words didn’t deter O’Mahoney...so, possibly to stop the planned invasion, but also perhaps to keep the American war materials from capture by the British warships in the area, Meade took possession of the Fenian arms ship as it steamed into Eastport Harbor and sent it back to New York under control of his artillerymen. This was effective in depriving the Irish Army of their weapons and so thwarted this first Canadian invasion attempt by members of the Irish Brigade. As O’Mahoney’s army disbanded on the 19th of April, the shipload of supplies was sailed “down east” to New York City where the Federal government returned both the ship and its cargo intact to the I.R.B.

The British thought this was the attack they had been told was scheduled for St. Patrick’s Day and believed the Fenian invasion threat was now over. Having accepted Robert’s appointment as his faction’s Secretary of War, General Sweeny left the United States Army temporarily in December 1865 to put the Canadian invasion plans in motion. At the end of May, 1866, he met in Buffalo with Brigadier General William F. Lynch, former Colonel of the 58th Illinois, Colonel John Hoy, formerly of the 21st New York, General John O’Neill, former Colonel of the 7th Michigan Cavalry, Colonel Owen Starr, former cavalry commander under General Hugh Kilpatrick in Sherman’s Army, and others to make final invasion plans.

The plan was to be set in motion on May 31st, 1866 when the main Irish Republican Army of 16,800 men was to cross the border at Buffalo and spearhead a three-pronged attack on Lower Canada moving through Toronto to Montreal and on to Quebec City. Simultaneously, two other Fenian armies were supposed to move against western Canada from staging areas in Chicago and Cleveland. A force of 3,000 had been assembled in Chicago and they were to advance to Detroit where they would cross into Canada at Windsor and threaten Toronto. Another army of 5,000 men in Cleveland was to cross Lake Erie to London and also threaten Toronto. It was the job of these two to draw the British troops away from the capital city of British North America leaving it and the city of Montreal open to the main Fenian army which was to cross the border at Buffalo and attack Fort Erie near Niagara Falls. After taking Toronto, they were to move on to Montreal which would fall with the help of a force moving up from St. Albans, Vermont and with the help of the Montreal Irish and the French radicals who hated the British. After capturing Montreal, they would move on to Quebec City while Fenian warships sealed off the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to prevent aid from coming to Quebec.

If the Army could not take Quebec, it would take Sherbrooke and leave Quebec City in isolation. The force that finally attacked Canada on June 1st numbered 1,300 rather than the 16,800 planned. Under General O’Neill this small Fenian army crossed the Niagara River near Buffalo and captured Niagara Village and Fort Erie where the tricolor flag of the present-day Irish Republic was raised for the first time. In turn, the Irishmen were attacked at Ridgeway by a Canadian volunteer militia force from Toronto and Hamilton which they defeated killing and wounding more than 50 of the Canadians.

The two western armies which were supposed to draw off the British forces from Toronto, failed to move. But, the following day, June 3rd, a force of 10,000 Canadian militia and 5,000 British regulars attacked the 1,300 Fenians. Opposed by overwhelming numbers, the Irish withdrew across the Niagara River by barge to Buffalo but were intercepted and arrested by the Captain of the warship the USS Harrison. O’Neill had hoped to regroup and strengthen his army by connecting up with the several thousand Irish volunteers who had gathered in villages and towns all along the New York-Canadian border to join the Fenian armies.

In the meantime, the indefatigable General Meade and 35 United States soldiers arrived in Ogdensburg, New York to again “persuade” the Fenians to cease their attacks on Canada. His commander, Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant, had journeyed to Buffalo to observe the Fenian activities and had ordered the border closed preventing 4,000 other Fenian troops from crossing at Fort Erie. Incidently, joining with the Irish troops were 500 Mohawk Indians from the Cattaraugus Reservation in New York and one company of 100 African-American veterans of the Union Army.

Meade then informed General Grant that carloads of Fenian arms and ammunition were due to arrive in the area by railroad and that he intended to capture them just as he had done in Maine. With Grant’s approval, Meade issued orders to all United States authorities and local law enforcement officers throughout the New York-New England region that these arms were to be seized as they entered the railroad yards. In this way, Meade captured all the Fenian war supplies as they arrived at New York City, St. Albans, Vermont, and Rouses Point, Potsdam Junction, and Watertown, New York.

Despite the Fenian Army’s numerical superiority, once Meade had deprived them of the means to carry out and sustain a fight and Grant had sealed off the Niagara River crossings, the unarmed troops massed along the border were unable to continue the invasion.

On June 6, a small force of 2,000 lightly armed Fenians did manage to cross at St. Albans, Vermont and captured the vilages of Frelighsburgh, St. Armand, Slab City, and East Stanbridge before being driven back. On that same day President Johnson issued a Proclamation forbidding any further Fenian attempts to break the neutrality laws of the United States. The British government had finally agreed to make a payment of $15,000,000 in reparations. While the Irish resented the President’s involvement in their plans, they did not act solely because of Johnson’s decree. Rather, it was the disarmament by General Meade that forced the Fenian leaders to put their schemes into abeyance awaiting a more propitious time to renew their attacks on Canada.

http://www.bivouacbooks.com/bbv2i3s6.htm0

Advertisement