Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

Ulster - the Famine Experience and other Stories

Options

Comments

-

-

-

Monty Burnz wrote: »Do you have good information on the farming methods of the Prebysterians versus those of the older Irish folks? If you are right about the chickens etc., perhaps in those days, as in Africa today, only the wealthier people could afford animals?

Back on track , and, you had different types of landholders/middlemen " landlords, landlord's agent, (tenant) farmers and cottiers (sub-tenants/labourers). Threse guys

http://www.attymass.ie/historical_documents/famine/conacre.pdf

So the landlord unless he was managing the property himself may not have gotten much of the rent thru the chain.0 -

How did people in areas with a lot of fishing fare?0

-

-

Advertisement

-

Fratton Fred wrote: »Now I remember my association with sheep and the Scots, the kilt was adopted so a frisky scotsman could catch an unsuspecting ewe offguard.

And the wellingtons were then invented to secure the hind legs.0 -

It's a mistake to read back into history and see it in today's terms. For centuries the economy of Ireland was not operating as a free choice economy. There were Cattle Acts that prevented the export of Irish beef because it would pose competition to the English beef exports; Wool Acts that essentially closed down the Irish wool trade for the same reason- all these resulted in Irish farmers having to turn to tillage to make a living. As a result by the early nineteenth century there was a heavy dependence on tillage farming. This was more precarious because of the booms and busts in crop prices usually surrounding war years.

The Flax growing industry thrived because of its uniqueness and it posed no threat to English economic interests. This was just a matter of luck more than anything else.0 -

fontanalis wrote: »How did people in areas with a lot of fishing fare?

Fishing wasn't developed in those days and boats were small.

No refridgeration, canning or salting etc and fish has a short life once caught.

And, fishing was also licenced. What was it like in NI ??

The Ulster economy also thrived in times of war and went into recession in peace time.

Looking at the employment figures indicates that the economic model was based more on trade and less on subsistance farming.

What Cromwell's General Ludlow said of Connaught was "not enough water to drown a man, wood enough to hang one, nor earth enough to bury him".

So the rules in Ulster were somewhat different.0 -

It's a mistake to read back into history and see it in today's terms. For centuries the economy of Ireland was not operating as a free choice economy. There were Cattle Acts that prevented the export of Irish beef because it would pose competition to the English beef exports; Wool Acts that essentially closed down the Irish wool trade for the same reason- all these resulted in Irish farmers having to turn to tillage to make a living. As a result by the early nineteenth century there was a heavy dependence on tillage farming. This was more precarious because of the booms and busts in crop prices usually surrounding war years.

The Flax growing industry thrived because of its uniqueness and it posed no threat to English economic interests. This was just a matter of luck more than anything else.

Are the effects of those acts not exaggerated though? Ireland would have had a sizeable internal market and the export of dairy products wasn't affected.

They were also lifted nearly a century before the famine.0 -

Fratton Fred wrote: »Are the effects of those acts not exaggerated though? Ireland would have had a sizeable internal market and the export of dairy products wasn't affected.

As our Ulster Scot friend has pointed out only people with money had cows and cash from those goods went for to pay rent.

The economy based on the spud and the cottier class -who were least educated - were entirely dependent on it.

And farmers grew their own food in an economy based on agriculture so the internal market did not exist.

So the question is how did this differ in Ulster or did it ?0 -

Advertisement

-

One of the ways for paying the fare for emigration was via indentured servitude

http://www.irelandoldnews.com/History/runaways.htm

http://www.boards.ie/vbulletin/showthread.php?t=20557551920 -

As our Ulster Scot friend has pointed out only people with money had cows and cash from those goods went for to pay rent.

The economy based on the spud and the cottier class -who were least educated - were entirely dependent on it.

And farmers grew their own food in an economy based on agriculture so the internal market did not exist.

So the question is how did this differ in Ulster or did it ?

The cattle and the dairy trade continued to be at the whimsies of the British war situations or trade interest - in the 1770s there were again embargoes on Irish cattle and butter exports because of the wars. But Irish tillage farmers got a huge boost during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s because of the need to feed the British Army. But the slump in prices in the 1820s proved disastrous.

But to get back to your question on Ulster there is a lot of information on the success of the linen trade in Ulster in L M Cullen's Economic history of Ireland. He calls the expansion of the linen industry in the 1780s 'remarkable' and this impacted on Ulster more than any other region. Cullen says - 'From Coleraine to Belfast the turnpike roads were built in the direction of Dublin to carry linen to Dublin'.0 -

Fratton Fred wrote: »I've always thought calling it The famine was wrong. It was a potato famine as all other crops were unaffected, unlike the famine 100 years earlier. Therefore, if people had money they could buy food, although this would have been at greatly inflated prices thanks to the middlemen and speculators exploiting the situation.

You make it sound like people could just nip into their local takeway for some Chinese. :rolleyes:

There was vast quantites of food exported under the watching eye of the British army.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Famine_(Ireland)#Food_exports_to_England0 -

Here is a good link to the Lisburn Workhouse

The impact of the Famine in the province of Ulster has sometimes been over-shadowed by the distress which occurred in the west of the country. Even within Ulster, however, there were considerable differences in the impact of the distress on the various Poor Law Unions. This ranged from the officially declared 'distressed' Union of Glenties in Co. Donegal which was-albeit reluctantly-financed by the government, to the highly regarded 'model' unions of Belfast and Newtownards which, throughout the Famine years, were able to remain self-financing. The following examination of the role of the Lisburn Workhouse during the Famine is intended to show how one Ulster Board of Guardians responded to these years of distress and to what extent their reactions were determined by particular local, economic and social conditions.

The potato blight, which was the immediate cause of the Famine, was first noticed in Co. Cork in September 1845 although the full extent of the damage it had caused was not realised until general digging took place it October. By this time it was obvious that blight had affected the potato crop primarily in the south and west of the country with only isolated instances appearing in Ulster.10 Consequently, there was no discernable increase in the demand for relief in Ulster in the latter part of 1845, a pattern which also held true for the Lisburn workhouse. At the end of October 1845, after a visit, the Marquis of Hertford and Captain Henry Marvell RN, MP for the town, commented in the Visitors' Book that they believed Lisburn's establishment was not excelled by any similar institution in England. The Marquis's approval even extended to providing, at his own expense a special dinner for the paupers, which consisted of beef, carrots and soup, followed by tea and currant buns.11

In order to meet the increase in distress which was expected in some parts of the country following the appearance of blight, the government introduced various temporary relief measures. Local relief committees were established which could receive grants for the provision of relief, grain was imported into the country, and the public works were given additional funds in order to provide employment. By providing these additions relief measures, the government hoped that they would be able to avoid extending the permanent system of Pool Law relief. Due to these policies, the demand for workhouse relief showed little change in the winter of 1845-6. In fact, the main change in the administration of the Poor Law was in regard to workhouse diet. As early as October 1845, the Poor Law Commissioners (the central governing body) informed all Poor Law Guardians it Ireland that they would allow potatoes - a stable part of the workhouse diet - to be replaced by other foodstuffs, such as bread, rice or soup. In the Lisburn Union, the guardians felt this to be unnecessary as they were still able to obtain good quality potatoes at the same price. By January 1846, however, the situation had changed and the local contractor was no longer able to obtain sound potatoes. In consequence, the Guardian: decided that instead of potatoes, the paupers should have soup four days a week, stirabout two days and potatoes only one day a week.13

In 1846 the potato harvest failed for the second time. In 1845 the impact of the blight had been localised but in 1846, the crop in every part of the country was affected.14 In the Lisburn Union, the crop failed totally.15 This had two major consequences: firstly, some of the rate payers, particularly the small farmers, found a difficult to pay their rates, and secondly, there was an increase in demand for workhouse relief. The Guardian responded to the hardship felt by smaller rate-payers by allowing them an additional two months to settle their accounts. They warned, however, that if rates were not then paid, they would take legal action against them.16

The increase in the number of workhouse inmates was a more immediate problem as, by November 1846 there were more people in the workhouse than it could accommodate (see fig. 2). This increase in demand to workhouse relief was repeated in practically every Poor Law Union in the country and was partly due to a change In policy by the government in the second year of distress. The relief measures introduced in 1845 were intended lobe temporary measures only. Following the reappearance of blight, however, the government determined to force the local landlords to play a larger role in the provision of relief. To facilitate this, public works were now extended throughout the country, although the unprecedented demand for relief meant that they were unable to provide sufficient employment for the distressed population. One of the consequences of the inability of the public works to provide sufficient relief was that an increasing number of people turned to local workhouses for support. The regional contrasts in this demand to relief are marked; in Co. Antrim, for example, the average number of people employed daily on the public work was 270-the lowest number in the whole of Ireland. This compares with a daily average of 335 in Co. Down 2,329 in Co. Tyrone, 4,065 in Co. Fermanagh and 9,002 in Co. Donegal. Even within Ulster, therefore, there were considerable regional contrasts which were even more marked when compared to the situation in the rest of the country: in Co. Clare, for example, 31,310 were employed daily on the public works, in Co. Galway there were 33,325 and in Co. Cork 42, 134.17 To a large extent, these regional variations reflect the levels of dependence of the local population on the potato as a stable crop. In many parts of Ulster, however, notably in the north eastern part, income derived from weaving provided a safely net against the worst effects of the blight.

In the winter of 1846-7 the demand for admittance to the Lisburn workhouse began to increase. Although there was little sickness in the institution, the Guardians were aware that infectious diseases might break out if overcrowding occurred They therefore responded to the demand by building additional sleeping galleries in the dormitories, to accommodate a further two hundred inmates. This accorded with the recommendations to the Poor Law Commissioners who under no circumstances wanted the Guardians to provide relief to people why were not residents of the workhouse.18 The reaction of the Lisburn Guardians is in sharp contrast to that of Guardians in many other parts of the country, particularly those where the public works were unable to provide sufficient relief. In these areas, many of the Guardians reacted to the second year of distress by introducing an ad hoc system of outdoor relief, even though it was absolutely forbidden under the terms of the Poor Law Act. Although this was most prevalent in the south and west of the country, in Co. Down both the Kilkeel and Banbridge Guardians intermittently provided illicit relief, despite repeated orders from the Poor Law Commissioner to desist.19 In Banbridge in April 1847, for example, the Guardians refused 1,271 persons workhouse relief because of overcrowding and instead gave each applicant food to take home.20

The inability of the government to provide sufficient relief through the public works, which resulted in a growing demand for workhouse relief, made a further change of policy inevitable. The government therefore decided that after August 1847 the Poor Law was to be the main provider of relief. To make this possible, outdoor relief was for the first tune to be officially permitted. Twenty-two unions along the western seaboard were officially declared `distressed' and were to receive external financial assistance, although the other unions were to remain self-supporting as far as possible. facilitate the change from public works to Poor Law relief, soup kitchens were established throughout Ireland during the summer of 1847, which, as their name suggests, provided relief in the form of soup. At its peak, over three million people in Ireland (almost half the population) availed themselves of this form of relief. Again, the regional variations are marked, the percentage of the population which received daily rations of soup in the Lisburn Union being 3 per cent, in Banbridge 17 per cent and in Larne 20 per cent. By contrast, in the Belfast, Newtownards and Antrim unions, soup kitchens proved to be unnecessary. The daily average in other parts of the country, particularly the west, was much higher than in Ulster. In the Gort Union 86 per cent of the population was in daily receipt of soup, in the Swinford Union the figure was 84 per cent and in the Clifden Union it was 87 per cent.21

The transfer to Poor Law relief in August 1847 coincided with a temporary depression in the linen industry which affected the small weavers of Cos. Antrim and Down. This had a short-term but significant impact on the number of people requiring relief in these areas. In the Lisburn union, the distress amongst the weavers made the provision of outdoor relief necessary. It was provided, however, subject to very stringent controls. For example, it was given only to the old or sick and was in the form of cooked food -stirabout - and not in cash. Simultaneously, relief provided within the workhouse was to be subject to tighter control in an effort to deter all but the really destitute from applying. Corn mills were to be erected in the workhouse, in which the able-bodied men were to be employed, whilst the female inmates were to be employed in oakum picking.22

Although blight reappeared in some parts of Ireland in the harvest of 1848, its impact on the Lisburn union was counter-balanced by a revival in the linen industry. As a result, the number of people seeking relief began to decline. The harvest of 1848, in fact, in many ways marked a watershed in the Famine. In the eastern part of Ulster, the worst was over; however, in other parts of the country, particularly along the western seaboard, the effect of a fourth year of distress was devastating. In the Lisburn union, there was an obvious reduction in the number of people seeking Poor Law relief. The return to 'normality' in the workhouse is perhaps indicated by the fact that in November 1848 the Marquis of Downshire, following a visit to the establishment, made a donation of one pound which he directed should be spent on the purchase of catechisms for the education of the pauper scholars. 23 There was, however, a temporary increase in mortality in the union when, in early 1849, a number of cases of asiatic cholera were reported in Lisburn. Similar outbreaks occurred in other parts of Ireland at this time, brought in from Britain through ports such as Londonderry, Dublin and Belfast. This cholera epidemic had a short-term impact on mortality rates throughout Ireland.

The continuation and, in some instances, increase in distress in some parts of Ireland in 1849, resulted in a shift of policy by the government. At the beginning of 1849, they introduced the Rate-in-Aid Act which imposed an additional rate on the more prosperous unions in Ulster and Leinster, which was then to be redistributed to the poorer unions in the west of Ireland.24 The purpose of this was to make poor relief a national rather than a local responsibility. The unions in Ulster primarily liable for this tax held meetings throughout the Province to protest at its introduction. The Lisburn Guardians described it as a tax on `the industrious population of Ulster for the support of the improvident and indigent poor of the south of Ireland' and ordered that placards be posted throughout the union to this effect. Advertisements were also to be placed in the Northern Whig, Belfast Commercial Chronicle and the Belfast News-Letter. They also convened a public meeting of all rate payers, to be held in the corn market in Lisburn on 3 March.15 However, in spite of the widespread unpopularity of the Rate-in-Aid Act amongst the Ulster Guardians it was generally paid although not as promptly as the usual poor rate.26

The potato crop in 1849 was relatively free from blight, which marked the start of a series of good harvests in Ireland. The exception to this was in parts of the west, particularly in a number of unions in Cos. Clare, Kerry and Galway, where the number of people seeking relief continued to grow .27 In the Lisburn union by June 1850, the number of inmates in the workhouse had returned to its pre-1845 level. In fact, the number of able-bodied men in the workhouse had dropped so drastically that the Guardians were forced to purchase an ass to work on the institution's farm." By August, the Guardians were sufficiently confident in the prospects of the local potato crop to re-introduce potatoes into the workhouse diet - three lbs a day to be given to all paupers over the age of nine.29

http://www.lisburn.com/books/historical_society/volume8/volume8-4.html0 -

You make it sound like people could just nip into their local takeway for some Chinese. :rolleyes:

There was vast quantites of food exported under the watching eye of the British army.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Famine_(Ireland)#Food_exports_to_England

That's not really helpful to be honest and that article isn't exactly the most accurate.

By the way, it doesn't mention the British army, it says under guard. Many wealthy farmers formed their own militia to protect their assets. This article provides more in http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Famine#PoliticalEconomymarketeconomicsandthefamine0 -

Fratton Fred wrote: »I've always thought calling it The famine was wrong. It was a potato famine as all other crops were unaffected, unlike the famine 100 years earlier.

I detest the term 'potato famine'. It makes it sound like the victims were the potatoes. You don't hear about the buckwheat famine of Sudan, the poppadum famine in Bangladesh, or the rice famine in Korea, do you? What does it matter what the failed crop was? The fact is that people couldn't get food, so they died.

In my view, referring to the 'Potato famine' trivialises and minimises the episode, and confirms cultural stereotypes to boot.0 -

Monty Burnz wrote: »I detest the term 'potato famine'. It makes it sound like the victims were the potatoes. You don't hear about the buckwheat famine of Sudan, the poppadum famine in Bangladesh, or the rice famine in Korea, do you? What does it matter what the failed crop was? The fact is that people couldn't get food, so they died.

In my view, referring to the 'Potato famine' trivialises and minimises the episode, and confirms cultural stereotypes to boot.

That's true, I've never looked at it like that. Is famine more accurate though? There was enough food to go around and the vast majority of people affected were dependant on the potato.

Maybe an gorta mor is a better description?0 -

Fratton Fred wrote: »That's true, I've never looked at it like that. Is famine more accurate though? There was enough food to go around and the vast majority of people affected were dependant on the potato.

Maybe an gorta mor is a better description?

Well you do see alot of people call it by english version of that: "The Great Hunger"

An Gorta Mór = The Great Hunger

The other name is "An Drochshaol" (The Bad Life/Time)

The famine of 1740/41 is know as "Bliain an Áir" = The Year of Slaughter0 -

There's no point in referring to food that they couldn't access, for whatever reason. Their normal food supply was cut off, and there was a famine.Fratton Fred wrote: »That's true, I've never looked at it like that. Is famine more accurate though? There was enough food to go around and the vast majority of people affected were dependant on the potato.

There's a short, but interesting article on Wikipedia here.0 -

I am inclined to accept Cormac O Grada's work on the Famine as being more authoritative than almost anything else. He does real history, with numbers.

I cannot readily lay hands on some of his works, and Google is surprisingly unhelpful. But there is a point that he has made: that the total amount of food produced in Ireland during the famine years, even if it had all been retained in Ireland, was insufficient to feed the population. Further, he points out that more food was imported during the famine than was exported

[O Grada, C. The Great Famine and Today's Famines in Cathal Poirteir (ed) The Great Irish Famine.]Dwelling on the exported grain ignores the reality that during the Famine grain exports were dwarfed by imports of cheaper grain, mainly maize. Moreover, the exported corn belonged not to the landless or near-landless masses, but Ireland's half a million farmers.

This point is ignored by many: those who sold corn into the export markets were also our ancestors, and probably those who ensured that it got safely loaded on to ships were also our Irish ancestors. Irish society in the middle of the 19th century was far from homogeneous, and involved many clashes of interest.

Since then, we have tended to re-interpret the past, putting all the blame for hard-heartedness on to the English (among whom we often include the wealthy Irish if they were Protestant) and we generally identify with those near-destitute people who suffered most when the famine happened.

My ancestors, people of limited means including Rundale farmers, got through the famine. The might have had a hard time, but they did not die of hunger or disease, nor did they emigrate. I suppose they witnessed some terrible things. When we mention the estimated two million victims of the famine, we take our eyes off the six million survivors -- but it is largely from that pool of survivors that today's Irish are descended.

I believe that some of the focus on the victims of the famine is an expression of survivor guilt. The great-great-grandchild of a large Kilkenny cereal farmer of 1847 might identify with the starving people, and be totally unaware that her ancestor sold grain for export.0 -

Advertisement

-

Fratton Fred wrote: »That's true, I've never looked at it like that. Is famine more accurate though? There was enough food to go around and the vast majority of people affected were dependant on the potato.

Maybe an gorta mor is a better description?

I am the OP.

Fred, famine is a word used to describe a scarcity of food affecting a large number of people.

When people say the Irish Famine or the Great Famine or the Great Hunger they are specifically refering to the period of 1845-1850 and the potato blight and related issues.

I pm'd a few regular posters who are into the history side of it to see if we could get a thread going on the Famine in Ulster. I am not really into the politics of it but the starvation side.0 -

... I am not really into the politics of it but the starvation side.

I think I understand what you intend, but it's difficult to disentangle the starvation from the politics, simply because the starvation was not evenly distributed over the population.

It would be good if we could separate the history from the myth-making.0 -

I am not really into the politics of it but the starvation side.

The look we had at trevelyan showed that politics and the administration had a massive role in the famine- http://www.boards.ie/vbulletin/showthread.php?p=72612478

What do you mean by 'the starvation side'? First hand accounts? Or what kind of 'other stories' in relation to thread title?0 -

P. Breathnach wrote: »

This point is ignored by many: those who sold corn into the export markets were also our ancestors, and probably those who ensured that it got safely loaded on to ships were also our Irish ancestors. Irish society in the middle of the 19th century was far from homogeneous, and involved many clashes of interest.

Since then, we have tended to re-interpret the past, putting all the blame for hard-heartedness on to the English (among whom we often include the wealthy Irish if they were Protestant) and we generally identify with those near-destitute people who suffered most when the famine happened.

My ancestors, people of limited means including Rundale farmers, got through the famine. The might have had a hard time, but they did not die of hunger or disease, nor did they emigrate. I suppose they witnessed some terrible things. When we mention the estimated two million victims of the famine, we take our eyes off the six million survivors -- but it is largely from that pool of survivors that today's Irish are descended.

I believe that some of the focus on the victims of the famine is an expression of survivor guilt. The great-great-grandchild of a large Kilkenny cereal farmer of 1847 might identify with the starving people, and be totally unaware that her ancestor sold grain for export.

The vast majority of the grain that was surrendered was given up for rents. The Irish small holder rarely had any money - it was a largely barter economy at that level. So the grain was not 'sold' - as I think you are suggesting - on the open market but was given to the landlord for rent. That was the system. The fear was if the grain was not given up to the landlord then eviction followed because the 'rent' was not paid- and this was frequent.

Also the victims and the survivors did not come from separate gene pools. The victims were for the most part related to the survivors - so to say that we are only descended from the survivors is not accurate. We are descended from both.

It is not wrong for any society to claim an allegiance with and commemorate a past tragedy. For some reason we have reached a point where the Irish are supposed to suck it up and keep quiet. The huge memorial and commemorations to the war dead held by the larger European former imperial nations passes without any comment - or even, applause. The Holocaust is also widely commemorated but for some reason - what? - we Irish are supposed to either keep quit or justify our own epitaphs to our tragic dead.0 -

Whenever the topic has gotten tackled here before politics has brought it down.

Scots-Irish are part of a Scottish Diaspora that went worldwide as owenc has pointed out.

http://www.genealogymagazine.com/scots.html

They came to Ulster as part of the Plantation to escape Episcopalian harrasment too.

Locally in Ulster the composition of the population and how they lived was largely down to both the British Government and the local English landowner. So Ulster was different for lots of reasons.

The "politics" did not evolve until later.

So thats why I am trying to look at this more from a social and local history way as that is the base on which it evolved.

The famine was fairly pivotal.

When in school we were taught that the reason that the Land League for instance was not a runner in NI was because of the Ulster Custom etc and Ulster was the land of milk and honey.

It really is hard to find a good Ulster history.So , why not test the theory .

Mr Charlotte Bronte (Arthur Nicholl) was from Ulster as was his father in law Patrick Bronte but they both had different views of the place. Arthur went back and became a farmer while Paddy looked down on or tried to forget his irish roots.0 -

jonniebgood1 wrote: »The look we had at trevelyan showed that politics and the administration had a massive role in the famine- http://www.boards.ie/vbulletin/showthread.php?p=72612478

Yes, Trevelyan was Permanent Head of the Treasury so his role covered both administrations during the Famine and he essentially had control over most of the economic decisions.

But most of the egregious laws were passed after the fall of Peel's government in 1846. The new PM Russell almost immediately [Oct 1846] issued a statement that he would have a hands-off approach to the starvation - 'It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people [in Ireland]. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so'.0 -

Whenever the topic has gotten tackled here before politics has brought it down.

Scots-Irish are part of a Scottish Diaspora that went worldwide as owenc has pointed out.

http://www.genealogymagazine.com/scots.html

They came to Ulster as part of the Plantation to escape Episcopalian harrasment too.

Locally in Ulster the composition of the population and how they lived was largely down to both the British Government and the local English landowner. So Ulster was different for lots of reasons.

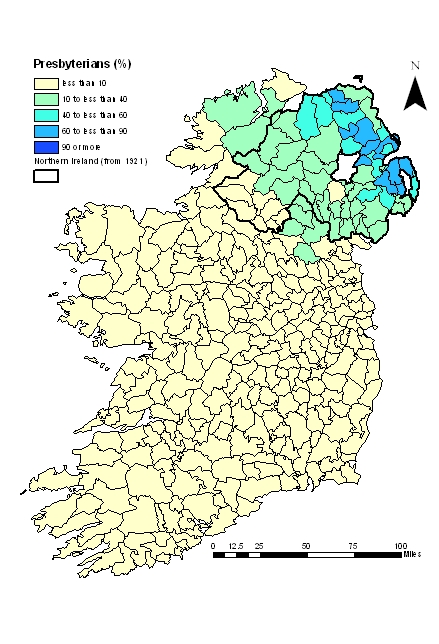

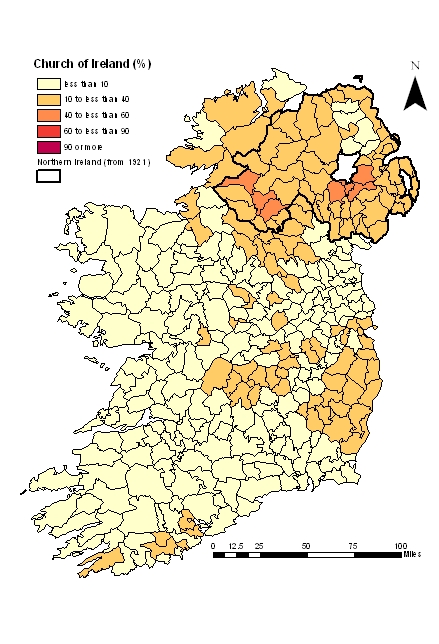

With regards to Scots settlement the following maps show correspondence between "Ulster scots dialects" and Presbytrianism. As you can see they generally overlap.

Church of Ireland distrubence map in correspondence shows large presence in Leinster (The Pale) and other areas where there would have been very little (next to none) scottish inflow as well as in the province of Ulster. 0

0 -

Also the victims and the survivors did not come from separate gene pools. The victims were for the most part related to the survivors - so to say that we are only descended from the survivors is not accurate. We are descended from both.

It is not wrong for any society to claim an allegiance with and commemorate a past tragedy. For some reason we have reached a point where the Irish are supposed to suck it up and keep quiet. The huge memorial and commemorations to the war dead held by the larger European former imperial nations passes without any comment - or even, applause. The Holocaust is also widely commemorated but for some reason - what? - we Irish are supposed to either keep quit or justify our own epitaphs to our tragic dead.

MD you are so eloquent.Yes, Trevelyan was Permanent Head of the Treasury so his role covered both administrations during the Famine and he essentially had control over most of the economic decisions.

But most of the egregious laws were passed after the fall of Peel's government in 1846. The new PM Russell almost immediately [Oct 1846] issued a statement that he would have a hands-off approach to the starvation - 'It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people [in Ireland]. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so'.

The history is local and Trevelyan was well covered and the Duke of Wellington born in Ireland had grave concerns in 1830 - 15 years before the event.

He called the system "evil".I confess that the annually recurring starvation in Ireland, for a period differing, according to the goodness or badness of the season, from one week to three months, gives me more uneasiness than any other evil existing in the United Kingdom.

It is starvation, because it is the fact that, although there is an abundance of provisions in the country of a superior kind, and at a cheaper rate than the same can be bought in any other part of Her Majesty’s dominions, those who want in the midst of plenty cannot get, because they do not possess even the small sum of money necessary to buy a supply of food.

It occurs every year, for that period of time that elapses between the final consumption of one year’s crop of potatoes, and the coming of the crop of the following year, and it is long or short, according as the previous season has been bad or good.

Now when this misfortune occurs, there is no relief or mitigation, excepting a recourse to public money. The proprietors of the country, those who ought to think for the people, to foresee this misfortune, and to provide beforehand a remedy for it, are amusing themselves in the Clubs in London, in Cheltenham, or Bath, or on the Continent, and the Government are made responsible for the evil, and they must find the remedy for it where they can—anywhere excepting in the pockets of Irish Gentlemen.

Then, if they give public money to provide a remedy for this distress, it is applied to all purposes excepting the one for which it is given; and more particularly to that one, viz. the payment of arrears of an exorbitant rent.

However, we must expect that this evil will continue, and will increase as the population will increase, and the chances of a serious evil, such as the loss of a large number of persons by famine, will be greater in proportion to the numbers existing in Ireland in the state in which we know that the great body of the people are living at this moment. [Wellington to Northumberland, 7 July 1830, in Despatches, vii 111–2; repr. in P. S. O’Hegarty, A history of Ireland under the Union (London 1952) 291–2]

http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Famine

We know all that, but what we do not know is how things played out locally in Ulster.0 -

The vast majority of the grain that was surrendered was given up for rents. The Irish small holder rarely had any money - it was a largely barter economy at that level. So the grain was not 'sold' - as I think you are suggesting - on the open market but was given to the landlord for rent. That was the system. The fear was if the grain was not given up to the landlord then eviction followed because the 'rent' was not paid- and this was frequent.

Also the victims and the survivors did not come from separate gene pools. The victims were for the most part related to the survivors - so to say that we are only descended from the survivors is not accurate. We are descended from both.

It is not wrong for any society to claim an allegiance with and commemorate a past tragedy. For some reason we have reached a point where the Irish are supposed to suck it up and keep quiet. The huge memorial and commemorations to the war dead held by the larger European former imperial nations passes without any comment - or even, applause. The Holocaust is also widely commemorated but for some reason - what? - we Irish are supposed to either keep quit or justify our own epitaphs to our tragic dead.

To be honest, I didn't read P. Breathnach's post that way (as in we shouldn't commemorate the famine). Good point on the 'suck it up' idea. A New History of Ireland: vol. V: Ireland Under the Union 1801-1870 ( ed. W.E Vaughan) has some excellent essays on the period from Economy and Society, 1830-1845 which looks at the dominance of tillage from the 1780s-1840s and cottiers and landless labourers (Oliver Mac Donagh). Land and People by T.W. Freeman. James S. Donnelly Jr has an extensive overview of all areas in Ireland during the famine which includes the Government Response, production, prices and exports, the adminstration of relief, the soup kitchens, landlords and tenants, excess mortality and emigration pp. 272-373. In particular, for the OP, he looks at Ulster, North Connacht and Leinster midlands in Excess Mortality and Emigration. Published by Oxford under the auspices of the Royal Irish Academy this series is a must and was originally planned by T.W Moody. This volume is well worth a read for this topic and is on sale!!0 -

Advertisement

-

On the issue of troops and military protecting food for export that some raised the information that we have from Trevelyan's report on the Famine gives us that data:Great exertions were made to protect the provision trade and the troops and constabulary [protecting the export of food] were harassed...

Convoys under military protection proceeded at stated intervals from place to place without which nothing in the shape of food could be sent [out of the country] with safety.0

Advertisement