Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

Hi there,

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

Gay Old Ireland - Whats the Story

-

12-03-2011 10:02am#1

Comments

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Advertisement

Advertisement

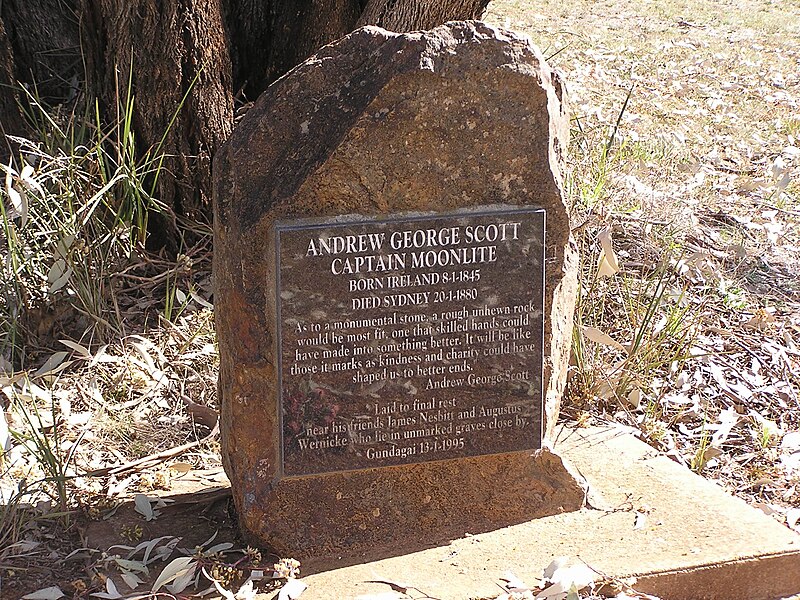

Andrew George Scott [Captain Moonlite] (1842 - 1880), by unknown engraver, 1879, courtesy of La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. IAN28/11/79/180. .

Andrew George Scott [Captain Moonlite] (1842 - 1880), by unknown engraver, 1879, courtesy of La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. IAN28/11/79/180. .

A cartoon about the United Ireland trial captioned "Flogging them to the fight: Earl Spencer having in vain attempted to crush United Ireland himself, by fair means, goads on the foulest scoundrels in the Castle Service, under pain of losing their salaries, to assail the obnoxious newspaper with a legal battering-ram of £40,000 damages".

A cartoon about the United Ireland trial captioned "Flogging them to the fight: Earl Spencer having in vain attempted to crush United Ireland himself, by fair means, goads on the foulest scoundrels in the Castle Service, under pain of losing their salaries, to assail the obnoxious newspaper with a legal battering-ram of £40,000 damages". The copy deposition of the Queen a. Cornwall & Others - Unnatural offenses

The copy deposition of the Queen a. Cornwall & Others - Unnatural offenses

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVlF-vqePxg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVlF-vqePxg