Advertisement

Help Keep Boards Alive. Support us by going ad free today. See here: https://subscriptions.boards.ie/.

https://www.boards.ie/group/1878-subscribers-forum

Private Group for paid up members of Boards.ie. Join the club.

Private Group for paid up members of Boards.ie. Join the club.

Hi all, please see this major site announcement: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058427594/boards-ie-2026

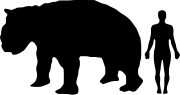

Creature of the week #4: Diprotodon

-

15-12-2009 12:28AM#1

Comments

Advertisement