Advertisement

If you have a new account but are having problems posting or verifying your account, please email us on hello@boards.ie for help. Thanks :)

Hello all! Please ensure that you are posting a new thread or question in the appropriate forum. The Feedback forum is overwhelmed with questions that are having to be moved elsewhere. If you need help to verify your account contact hello@boards.ie

Hi all! We have been experiencing an issue on site where threads have been missing the latest postings. The platform host Vanilla are working on this issue. A workaround that has been used by some is to navigate back from 1 to 10+ pages to re-sync the thread and this will then show the latest posts. Thanks, Mike.

Hi there,

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

There is an issue with role permissions that is being worked on at the moment.

If you are having trouble with access or permissions on regional forums please post here to get access: https://www.boards.ie/discussion/2058365403/you-do-not-have-permission-for-that#latest

Bank of England recognizes Endogenous Money

-

13-03-2014 12:44am#1This could fit in the MMT thread, but it's significant enough in its own right, for a thread of its own - this (even though it's not new, it corrects near-universal misconceptions) makes most macroeconomics textbooks obsolete, and corrects a very large amount of fundamental misconceptions about macroeconomics, which transform the topic completely.

The Bank of England discards the fractional-reserve/money-multiplier theory of money, and adopts endogenous money - the recognition that banks create money when they make loans:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf• This article explains how the majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans.

• Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits.

...

In the modern economy, most money takes the form of bank deposits. But how those bank deposits are created is often misunderstood: the principal way is through commercial banks making loans.

Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money.

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

• Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

• In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits.

Although commercial banks create money through lending, they cannot do so freely without limit. Banks are limited in how much they can lend if they are to remain profitable in a competitive banking system. Prudential regulation also acts as a constraint on banks’ activities in order to maintain the

resilience of the financial system. And the households and companies who receive the money created by new lending may take actions that affect the stock of money — they could quickly ‘destroy’ money by using it to repay their existing debt, for instance.

...

Here is a short video they have made as well, explaining it all:

"...loans create deposits, not the other way around"

Correcting these misconceptions about money, is (in my opinion) at the very heart - the starting point - of what is needed to correct the study and practice of economics, and it logically leads to stuff like MMT (which is basically a rewrite of macroeconomics, expressly written to take endogenous money into account).

Some more very important snippets, which reverse common (mis)understanding of macroeconomics (most emphasis mine):One common misconception is that banks act simply as intermediaries, lending out the deposits that savers place with them.

In this view deposits are typically ‘created’ by the saving decisions of households, and banks then ‘lend out’ those existing deposits to borrowers, for example to companies looking to finance investment or individuals wanting to purchase houses.

In fact, when households choose to save more money in bank accounts, those deposits come simply at the expense of deposits that would have otherwise gone to companies in payment for goods and services. Saving does not by itself increase the deposits or ‘funds available’ for banks to lend.

Indeed, viewing banks simply as intermediaries ignores the fact that, in reality in the modern economy, commercial banks are the creators of deposit money. This article explains how, rather than banks lending out deposits that are placed with them, the act of lending creates deposits — the reverse of the sequence typically described in textbooks.

Another common misconception is that the central bank determines the quantity of loans and deposits in the economy by controlling the quantity of central bank money — the so-called ‘money multiplier’ approach.

In that view, central banks implement monetary policy by choosing a quantity of reserves. And, because there is assumed to be a constant ratio of broad money to base money, these reserves are then ‘multiplied up’ to a much greater change in bank loans and deposits. For the theory to hold, the amount of reserves must be a binding constraint on lending, and the central bank must directly determine the amount of reserves.

While the money multiplier theory can be a useful way of introducing money and banking in economic textbooks, it is not an accurate description of how money is created in reality.

Rather than controlling the quantity of reserves, central banks today typically implement monetary policy by setting the price of reserves — that is, interest rates.

In reality, neither are reserves a binding constraint on lending, nor does the central bank fix the amount of reserves that are available. As with the relationship between deposits and loans, the relationship between reserves and loans typically operates in the reverse way to that described in some economics textbooks. Banks first decide how much to lend depending on the profitable lending opportunities available to them — which will, crucially, depend on the interest rate set by the Bank of England. It is these lending decisions that determine how many bank deposits are created by the banking

system. The amount of bank deposits in turn influences how much central bank money banks want to hold in reserve (to meet withdrawals by the public, make payments to other banks, or meet regulatory liquidity requirements), which is then, in normal times, supplied on demand by the Bank of England.

...

broad money is a measure of the total amount of money held by households and companies in the economy.

Broad money is made up of bank deposits — which are essentially IOUs from commercial banks to households and companies — and currency — mostly IOUs from the central bank.

Of the two types of broad money, bank deposits make up the vast majority — 97% of the amount currently in circulation. [KB: i.e. 97% of money in circulation is created by banks]

And in the modern economy, those bank deposits are mostly created by commercial banks themselves.

Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When a bank makes a loan, for example to someone taking out a mortgage to buy a house, it does not typically do so by giving them thousands of pounds worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits their bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the mortgage.

At that moment, new money is created.

For this reason, some economists have referred to bank deposits as ‘fountain pen money’, created at the stroke of bankers’ pens when they approve loans.

...

reserves are, in normal times, supplied ‘on demand’ by the Bank of England to commercial banks in exchange for other assets on their balance sheets. In no way does the aggregate quantity of reserves directly constrain the amount of bank lending or deposit creation.

This description of money creation contrasts with the notion that banks can only lend out pre-existing money, outlined in the previous section. Bank deposits are simply a record of how much the bank itself owes its customers. So they are a liability of the bank, not an asset that could be lent out. A related misconception is that banks can lend out their reserves. Reserves can only be lent between banks, since consumers do not have access to reserves accounts at the Bank of England.

...

Just as taking out a new loan creates money, the repayment of bank loans destroys money.

On the real constraints to lending (as opposed to the common myths):In the modern economy there are three main sets of constraints that restrict the amount of money that banks can create.

(i) Banks themselves face limits on how much they can lend. In particular:

• Market forces constrain lending because individual banks have to be able to lend profitably in a competitive market.

• Lending is also constrained because banks have to take steps to mitigate the risks associated with making additional loans.

• Regulatory policy acts as a constraint on banks’ activities in order to mitigate a build-up of risks that could pose a threat to the stability of the financial system.

(ii) Money creation is also constrained by the behaviour of the money holders — households and businesses.

Households and companies who receive the newly created money might respond by undertaking transactions that immediately destroy it, for example by repaying outstanding loans.

(iii) The ultimate constraint on money creation is monetary policy.

By influencing the level of interest rates in the economy, the Bank of England’s monetary policy affects how much households and companies want to borrow.

This occurs both directly, through influencing the loan rates charged by banks, but also indirectly through the overall effect of monetary policy on economic activity in he economy. As a result, the Bank of England is able to ensure that money growth is consistent with its objective of low and stable inflation.0

Comments

-

Here's an article on this from the Irish economist Phil Pilkington, who points out some further important details, that the BoE gets wrong, and which they have yet to reform their stance on:

https://fixingtheeconomists.wordpress.com/2014/03/12/bank-of-england-endorses-post-keynesian-endogenous-money-theory/

Plus a further followup:

https://fixingtheeconomists.wordpress.com/2014/03/13/a-new-era-of-central-banking/0 -

Moderators, Science, Health & Environment Moderators, Society & Culture Moderators Posts: 3,372 Mod ✭✭✭✭

Join Date:Posts: 3262

Join Date:Posts: 3262

I'm not convinced that that paper says things which are particularly new, except maybe to the public. Or perhaps I just don't see the differences:

For example, as the book we used for 1st year intro to Macro says:So even though each bank only lends the money it receives, the banking system as a whole does create money by making loans

which seems similar to the paper you link, which says:Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans.

Another quote from the intro book:But effectiveness of monetary policy also depends on how much expenditure changes. If expenditure is not very responsive to a change in the interest rate, monetary actions do not have much effect on expenditure. But if expenditure is highly responsive to a change in the interest rate, monetary actions have a large effect on aggregate expenditure. The greater the responsiveness of expenditure to the interest rate, the more effective is monetary policy

What the paper says:ii) Money creation is also constrained by the behaviour of the money holders — households and businesses.

Households and companies who receive the newly created money might respond by undertaking transactions that immediately destroy it, for example by repaying outstanding loans.

And another quote from an intro book:The repo rate is the interest rate at which the Bank of England stands ready to make loans to commercial banks. The Bank of England uses repurchase agreements (repos) to make these loans. A rise in the repo rate makes it more costly for banks to borrow from the Bank of England and encourages them to cut their lending, which decreases the supply of money and increases other interest rates. A fall in the repo rate makes it less costly for banks to borrow from the Bank of England and stimulates bank lending, which increases the supply of money and lowers other interest rates.

and the paper:(iii) The ultimate constraint on money creation is monetary policy.

By influencing the level of interest rates in the economy, the Bank of England’s monetary policy affects how much households and companies want to borrow.

This occurs both directly, through influencing the loan rates charged by banks, but also indirectly through the overall effect of monetary policy on economic activity in he economy. As a result, the Bank of England is able to ensure that money growth is consistent with its objective of low and stable inflation

The authors themselves note in a footnote that:There is a long literature that does recognise the ‘endogenous’ nature of money creation in practice. See, for example, Moore (1988), Howells (1995) and Palley (1996)

The authors also say that:Reserves can only be lent between banks, since consumers do not have access to reserves accounts at the Bank of England.

which is something that all Economists would know, and and note in an associated footnote thatPart of the confusion may stem from some economists’ use of the term ‘reserves’ when referring to ‘excess reserves’ — balances held above those required by regulatory reserve requirements. In this context, ‘lending out reserves’ could be a shorthand way of describing the process of increasing lending and deposits until the bank reaches its maximum ratio. As there are no reserve requirements in the

United Kingdom the process is less relevant for UK banks.

Which seems to indicate pretty strongly that this is a paper aimed to address misconceptions on the part of the public, not Economists. Admittedly, I haven't had time to read the entire paper.0 -

Well, if you contrast the two statements, they're actually contradictory:So even though each bank only lends the money it receives, the banking system as a whole does create money by making loans

That's the 'loanable funds' theory, which isn't compatible with endogenous money, which is what the BoE is putting forward.BoE wrote:Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans.

The crux of what the BoE puts forward is that investments lead to savings; i.e. loans lead to deposits - loans also lead to reserves, and this contradicts the bolded part above (it reverses a lot of the common understanding) - this means the fractional-reserve/money-multiplier theory of money (which tie in to loanable funds) is false, even though they are still commonly taught.

Does any of that seem new/disagreeable? (if not, I may try to dig more into the topic, to find out in more detail, what the exact issues are that endogenous money supporters take)

Another point of contention that you mention (but is less related), is the interest rate: I'm not that knowledgeable about arguments surrounding that, but I believe there are a lot of theoretical problems with looking at interest rates as an effective monetary policy tool.

One argument against that, is that (when it comes to the quantity of money) the demand for credit is the primary determinant (which is an 'endogenous' variable - i.e. it's determined from within the economy) instead of the interest rate (an 'exogenous' variable - controlled from outside the economy, in the central bank), and that the control you have with the interest rate is not that good.

While the interest rate certainly affects the demand for credit, this in turn depends upon conditions in the economy: Right now we see near-zero interest rates, yet not enough lending (due to too much debt), and in boom-times, high GDP growth allows much better tolerance of high interest rates; it's a pretty bad/blunt means of control.

The rest of these quotes, while relating to monetary policy, don't relate to money creation directly - they are an important part of the debate though, particularly on the interest rate, but I am not that familiar with what proponents of endogenous money (the Post-Keynesians mostly) take issue with there.Another quote from the intro book:

What the paper says:

And another quote from an intro book:

and the paper:

The authors themselves note in a footnote that:

The authors also say that:

which is something that all Economists would know, and and note in an associated footnote that

Which seems to indicate pretty strongly that this is a paper aimed to address misconceptions on the part of the public, not Economists. Admittedly, I haven't had time to read the entire paper.

The rest of the BoE document isn't really necessary to look through I think - it mainly just covers the details summarized earlier, in exhaustive detail.

You're right that this is, in a sense, all 'old news' - because some economists have known all of this for (at least) half a century - but what is not old news, is that there are a lot of subtle debates still surrounding this overall topic, and there is a lot that most economists (particularly mainstream/neoclassical) economists still get wrong on this topic - that even the BoE still gets wrong (even though they've taken a leap forward, with what they've put out).0 -

Steve Keen - who I usually cite when discussing this topic - has done a good article on this, which mirrors what I said in my previous post there (on fractional-reserve/money-multiplier theory):

http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2014/3/18/economy/boes-sharp-shock-monetary-illusions...I’m doffing my cap to the researchers at Threadneedle Street for a new paper “Money creation in the modern economy,” which gives a truly realistic explanation of how money is created, why this really matters, and why virtually everything that economic textbooks say about money is wrong.

...

It clearly wants economic textbooks to throw out the neat, plausible but wrong rubbish they currently teach about money, and connect with the real world instead.

Economic textbooks teach students that money creation is a two-stage process. At the start, banks can’t lend because of a rule called the “Required Reserve Ratio” that specifies a ratio between their deposits and their reserves. If they’re required to hold 10 cents in reserves to back every dollar in deposits, then if deposits are $10 trillion and reserves are $1 trillion, the banking sector can’t lend any money to anyone.

Stage one in the textbook money creation model is that the Fed (or the Bank of England) gives the banks additional reserves -- say $100 billion worth. Then in stage two, the banks lend this to their customers, who then deposit it right back into banks, who hang on to 10 per cent of it ($10 billion) and lend the remaining $90 billion out again. This process iterates until an additional $1 trillion of deposits are created, so that the reserve ratio is restored ($1.1 trillion in reserves, $11 trillion in deposits).

That model goes by the name of “Fractional Reserve Banking” (aka the “Money Multiplier”), and depending on your political persuasion it’s either outright fraud (If you’re of an Austrian persuasion like my mate Mish Shedlock) or just the way things are if you’re a mainstream economist like Paul Krugman. In the latter case, it lets conventional economists build models of the economy that completely ignore the existence of banks, and private debt, and in which the money supply is completely controlled by the Fed.

In this new paper, the Bank of England states emphatically that “Fractional Reserve Banking” is neither fraud, nor the way things are, but a myth -- and it rightly blames economic textbooks for perpetuating it. The paper doesn’t beat about the bush when it comes to the divergence between reality and what economic textbooks spout.

...

I'd count Keen as one of the primary experts out there, on the faults in mainstream economics, due to his book Debunking Economics - and so he does a very good job at getting down to the details of why this is important.0 -

Here is David Graeber's take on BoE's statement, and it is an important read, as it is the most lucid explanation I've seen thus far, of the significance of this:The truth is out: money is just an IOU, and the banks are rolling in it

The Bank of England's dose of honesty throws the theoretical basis for austerity out the window

Back in the 1930s, Henry Ford is supposed to have remarked that it was a good thing that most Americans didn't know how banking really works, because if they did, "there'd be a revolution before tomorrow morning".

Last week, something remarkable happened. The Bank of England let the cat out of the bag. In a paper called "Money Creation in the Modern Economy", co-authored by three economists from the Bank's Monetary Analysis Directorate, they stated outright that most common assumptions of how banking works are simply wrong, and that the kind of populist, heterodox positions more ordinarily associated with groups such as Occupy Wall Street are correct. In doing so, they have effectively thrown the entire theoretical basis for austerity out of the window.

This part in particular is critical:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/18/truth-money-iou-bank-of-england-austerityTo get a sense of how radical the Bank's new position is, consider the conventional view, which continues to be the basis of all respectable debate on public policy. People put their money in banks. Banks then lend that money out at interest – either to consumers, or to entrepreneurs willing to invest it in some profitable enterprise. True, the fractional reserve system does allow banks to lend out considerably more than they hold in reserve, and true, if savings don't suffice, private banks can seek to borrow more from the central bank.

The central bank can print as much money as it wishes. But it is also careful not to print too much. In fact, we are often told this is why independent central banks exist in the first place. If governments could print money themselves, they would surely put out too much of it, and the resulting inflation would throw the economy into chaos. Institutions such as the Bank of England or US Federal Reserve were created to carefully regulate the money supply to prevent inflation. This is why they are forbidden to directly fund the government, say, by buying treasury bonds, but instead fund private economic activity that the government merely taxes.

It's this understanding that allows us to continue to talk about money as if it were a limited resource like bauxite or petroleum, to say "there's just not enough money" to fund social programmes, to speak of the immorality of government debt or of public spending "crowding out" the private sector. What the Bank of England admitted this week is that none of this is really true. To quote from its own initial summary: "Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits" … "In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money 'multiplied up' into more loans and deposits."

In other words, everything we know is not just wrong – it's backwards. When banks make loans, they create money. This is because money is really just an IOU. The role of the central bank is to preside over a legal order that effectively grants banks the exclusive right to create IOUs of a certain kind, ones that the government will recognise as legal tender by its willingness to accept them in payment of taxes. There's really no limit on how much banks could create, provided they can find someone willing to borrow it. They will never get caught short, for the simple reason that borrowers do not, generally speaking, take the cash and put it under their mattresses; ultimately, any money a bank loans out will just end up back in some bank again. So for the banking system as a whole, every loan just becomes another deposit. What's more, insofar as banks do need to acquire funds from the central bank, they can borrow as much as they like; all the latter really does is set the rate of interest, the cost of money, not its quantity. Since the beginning of the recession, the US and British central banks have reduced that cost to almost nothing. In fact, with "quantitative easing" they've been effectively pumping as much money as they can into the banks, without producing any inflationary effects.

What this means is that the real limit on the amount of money in circulation is not how much the central bank is willing to lend, but how much government, firms, and ordinary citizens, are willing to borrow. Government spending is the main driver in all this (and the paper does admit, if you read it carefully, that the central bank does fund the government after all). So there's no question of public spending "crowding out" private investment. It's exactly the opposite.

...

You can see from the last paragraph as well, how this ties directly into MMT.

Here is another good blog entry, giving an overview of the news and peoples writing on it so far:

http://www.theautomaticearth.com/the-bank-of-england-lights-a-fuse-under-the-field-of-economics/0 -

Advertisement

-

Really good article, again from the Irish economist Phil Pilkington, which points out how Monetarism is still at play in economic policy, and how the BoE's statement is a partial rejection of that - and, how another critical component of Monetarism is still in play: Using unemployment to manage inflation.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/22/monetarism-economic-theory-bank-of-england-governmentPhil Pilkington wrote:...

The second component, however, is alive and well. That is the idea that the central bank should use unemployment to control inflation. Although the central banks of the world rarely say it in public, since the monetarist era they have used interest rate hikes to generate recessions and increase unemployment any time they fear an uptick in inflation. The environment of wage suppression that this tactic has engendered is one of the primary reasons that households have had to borrow so much money in recent times. Indeed, this second component of monetarism is one of the primary culprits behind the economic crisis that we have been living through for the past five years.

The Bank's report continues to insist that it should use the interest rate to manage the level of economic activity. This is despite the fact that even the extraordinarily low interest rates of the past five years have failed to produce a sustained recovery. But its recent admission has pointed to a very different conception of what a central bank should do: namely, that the central bank's primary goal is to provide funding for the government.

Indeed, this is precisely why the Bank of England was set up 1690. William III needed a powerful navy to defeat the French and so he incorporated the Bank. This conception of what a central bank should be implies that it is the government, not the central bank, that is responsible for managing the level of economic activity. It does this through its spending and taxation policies. In an upturn it raises taxes to dampen inflation, and in a downturn it increases spending to generate economic activity.

The central bank, in such a view, takes a back seat. It merely provides the funds for the government at a set rate of interest and provides ministers with neutral advice on what they should be doing. In this view, unemployment is not to be seen as desirable at all. In a period of inflation the government sucks money out of the system by taxing it away – and if wages and prices continue to rise the government imposes a tax on companies and workers that are not complying.

Obviously the current government is not competent enough to spearhead this revolution, so tied are they to their archaic economic theories and failed policies. But innovative economists at the Bank of England are showing that they could be the ones to lead the way. Last week they put a final nail in monetarism's coffin. If they want to finish the job they might unseal the lid and drive a stake through its heart lest it arise from the dead.

Typically, you never hear of unemployment as being an essential inflation-management policy, yet that - indirectly - is exactly what it is.

Other policies, like the Job Guarantee (having government as employer of last resort), are also inflation management policies (and are more efficient at the job than unemployment, too) - but instead of pushing people into unemployment to manage inflation, it pushes them from the private sector, into lower-paid Job Guarantee positions (with taxes also being used as an inflation-management mechanism, to target inflating areas of the private economy).0 -

Moderators, Science, Health & Environment Moderators, Society & Culture Moderators Posts: 3,372 Mod ✭✭✭✭

Join Date:Posts: 3262

Join Date:Posts: 3262

I've had a full read of the thing now. I can see how it differs from the textbook now, though I'd be lying if I said I fully understood all of it. I particularly like the explanation of QE.

That said, I still wouldn't overemphasise it's significance. I'm not going to pretend that I or everyone who studied economics knew all of this before reading that paper, but the paper still seems like more of a communication of what many Central Bank economists already knew, rather than a seminal new perspective.

Also, I'm not sure I buy what Pilkington says. The paper, on my reading, still suggests a significant role for Central Banks in terms of managing the economy, and that's even before considerations of Macroprudential policy come in.0 -

Yes I didn't read the whole lot myself, e.g. skipped the latter half which was more about the nuts-and-bolts of what the first half summarized.

I would say that yes, for some economists - most particularly central bank economists - many are likely to have known this already, but I still think it is extremely notable - as so many economists (e.g. some well known ones like Krugman) have been getting this wrong for a very long time

It's a very big change to have this finally becoming the dominant mainstream view - and the heterodox Post-Keynesians are certainly very happy to see this happen, because it should mean that more Post-Keynesian views start to enter the mainstream as well.

I've done some further reading up, to try and outline some things about this which are particularly notable, which I get into below (two things mainly: debt-deflation and what is needed to recover from that, and inefficiency of interest rate adjustments - not an expert though, so there are probably other more important things); sorry for the length, just trying to address each issue well.

Endogenous money gives particular credibility to the Debt Deflation theory of the bussiness cycle - and when you look at the solutions to resolving debt deflation, you see that they are the opposite of what is being done now:

- We need debt relief. Currently, even when a bank 'writes off' debt, it's not really written off as the country still pays for it - this needs to be properly written off right up to the ECB level.

- We need fiscal stimulus, i.e. increased government spending and decreased taxes; doing this with increased government debt just shifts the problem from the private to the public sphere, so the only sustainable way is through non-debt-based money, i.e. government spending created money, without added debt.

- Increased inflation is also desired, for reducing the debt load - this would primarily come from increased spending, and banks are not in a position to provide this (interest rates are already at record lows, with little further demand for loans), only government is really in a position to do this right now.

This is similar to the kind of policies I advocate, under MMT - endogenous money is the base that pretty much all of that, is built upon - so endogenous money becoming more mainstream, is also critically important as it is the first step in leading to a transformation in macroeconomics, based on Post-Keynesian views like in MMT.

Also, on the interest rate (a much wider topic, which touches on yet more issues in standard economic thinking/teaching; this gives quite a good overview of the PK views here), while it still allows some central bank control, it is grossly insufficient at regulating the money supply, and just about any area of the economy, in a useful way, especially when you consider the business cycle and how the acceptable rate of interest (i.e. what businesses will accept, not how the rate is set) is determined at a business level:

In an economy that is booming (particularly one with a poorly regulated banking/financial sector - still the case almost everywhere), businesses will decide what rate of interest they are willing to tolerate, based upon expected profitability - and if they are still expecting significant growth surpassing the cost of increased interest, they keep borrowing.

Then you have three classes of businesses (and also of banks - most of what I describe below applies to banks as well):

1: Sustainable: Profitable, even in the face of increased interest rates - can become Risky upon interest rate increase.

2: Risky: Barely profitable, may become unprofitable in face of increased interest - can become Ponzi upon interest rate increase.

3: Ponzi: Not profitable, future survival depends upon expanding business using debt, and paying only the interest (not principal) - can default upon interest rate increase, but will tend to grow at all costs (often fraudulently).

So in a situation where the economy is growing, but there is increasing inflation, central banks may not have a very good control over inflation and the money supply, when businesses are still expecting growth.

Businesses that are Sustainable or Risky, may see the growth of the economy as allowing them to take on debt at increased interest, where it still allows a profit - and Ponzi businesses, will take on increased debt just as a matter of survival, regardless of sustainability.

So, inflation may still be pushed hard, even in the face of increased interest rates - then it may happen that a shock to the economy occurs, slowing down growth (typically an unexpected thing during a bubble), which may push Sustainable bussiness into being Risky (not necessarily a problem, they can just cut back), Risky businesses into Ponzi (suddenly they depend upon debt for their very survival), and reduces the growth/remaining-lifetime of existing Ponzi's.

In that situation, depending on the size of the economic shock, you may see a brief slowdown and then a recovery to growth, but with greater proportion of Ponzi-based business, which depend upon inflating bubbles for survival, leading to much greater instability in the future.

Eventually, heading into the tail-end of the business cycle, the instability will build up, to the point that an economic shock will collapse the Ponzi's, leading to wider damage to business/growth, and potentially to debt-deflation.

So overall, on its own, interest rates are (even monetary policy in general is) a very poor policy tool - what is really needed, is proper regulation (tackling overly risky and/or ponzi-like business directly), combined with using fiscal policy instead, to manage the economy (taxes managing inflation, spending managing full-employment targetting - among other things).

A lot of Post-Keynesian's even argue for a zero rate of interest, but with proper regulation to stop money being put into unsustainable/bubble/ponzi type investments.

You can have this kind of a setup (basically, the central bank acting primarily as a regulatory institution - so they still have control over private bank lending/money-creation), while also completely absorbing administration of the monetary system itself, into the hands of government (who, in addition to managing the economy with fiscal policy, would never again have to rely upon public debt for fiscal funding).0 -

Here's an article from the author Ellen Brown, which (in among giving an excellent overview of the status and future of Europe, which I recommend reading just for that), touches on the BoE's statement, and also echo's my own views on money creation, and how governments should be given the power to make use of this (this isn't limited to MMT; Ellen is a monetary reformist, who I believe does not support MMT).

https://www.commondreams.org/view/2014/03/29-4...

A Third Alternative – Turn the Government Money Tap Back On

A giant flaw in the current banking scheme is that private banks, not governments, now create virtually the entire money supply; and they do it by creating interest-bearing debt. The debt inevitably grows faster than the money supply, because the interest is not created along with the principal in the original loan. [KB: This is another contributing part of the business cycle: Debt literally grows faster than money, meaning the Debt:Money ratio grows over time, e.g. 10x Debt:Money, 40x, 100x etc., and must eventually end in a bust, mass loan defaults, as this is unsustainable. Government 'debt-free' money, doesn't have this problem.]

For a clever explanation of how all this works in graphic cartoon form, see the short French video “Government Debt Explained,” linked here.

The problem is exacerbated in the Eurozone, because no one has the power to create money ex nihilo as needed to balance the system, not even the central bank itself. This flaw could be remedied either by allowing nations individually to issue money debt-free or, as suggested by George Irvin, by giving a joint Eurozone Treasury that power.

The Bank of England just admitted in its Quarterly Bulletin that banks do not actually lend the money of their depositors. What they lend is bank credit created on their books. In the U.S. today, finance charges on this credit-money amount to between 30 and 40% of the economy, depending on whose numbers you believe. In a monetary system in which money is issued by the government and credit is issued by public banks, this “rentiering” can be avoided. Government money will not come into existence as a debt at interest, and any finance costs incurred by the public banks’ debtors will represent Treasury income that offsets taxation.

New money can be added to the money supply without creating inflation, at least to the extent of the “output gap” – the difference between actual GDP or actual output and potential GDP. In the US, that figure is about $1 trillion annually; and for the EU is roughly €520 billion ($715 billion). A joint Eurozone Treasury could add this sum to the money supply debt-free, creating the euros necessary to create jobs, rebuild infrastructure, protect the environment, and maintain a flourishing economy.

See, a critically important part of the BoE's statement, is it now legitimises thinking about money, in terms of 'money creation' and 'money destruction' (or better put: removal from circulation, as no money is actually 'destroyed') - and then, talking about whether it's appropriate for private banks to have that power, or whether that should be put under democratic/public control through government instead.

So, the BoE statement also goes a long way to legitimising the narrative/framing of arguments, of not just monetary reformists like Ellen Brown, but also for Post-Keynesians in general, and the Modern Money Theory guys.0 -

I'm not sure how this shatters the case for austerity. As alluded to already, although many might have a simple fractional reserve view of money creation, many don't, including those who advocate austerity. Mike Shedlock an Austrian most definately is fully aware of everything mentioned in the OP. He still remains an austerian as Krugman likes to put it. David Graeber is getting a little carried away here:they stated outright that most common assumptions of how banking works are simply wrong, and that the kind of populist, heterodox positions more ordinarily associated with groups such as Occupy Wall Street are correct. In doing so, they have effectively thrown the entire theoretical basis for austerity out of the window.0

-

Advertisement

-

KyussBishop wrote: »The crux of what the BoE puts forward is that investments lead to savings; i.e. loans lead to deposits - loans also lead to reserves,

I only see BoE quotes acknowledging the bolded part. I agree in a loose sense, but how do investments lead to savings according to MMT?0 -

What is the current remaining case for austerity?I'm not sure how this shatters the case for austerity. As alluded to already, although many might have a simple fractional reserve view of money creation, many don't, including those who advocate austerity. Mike Shedlock an Austrian most definately is fully aware of everything mentioned in the OP. He still remains an austerian as Krugman likes to put it. David Graeber is getting a little carried away here:

Actually, I'm mixing 'investments lead to savings' up with the loans lead to deposits statement; I believe both tie in together closely, but I don't know enough in detail about the 'investments lead to savings' argument, to elaborate on it here.I only see BoE quotes acknowledging the bolded part. I agree in a loose sense, but how do investments lead to savings according to MMT?

There's a fairly detailed take on it here, but I can't immediately find a good 'plain English' description anywhere:

http://heteconomist.com/planned-investmentsaving-and-keynesian-causation/0 -

KyussBishop wrote: »What is the current remaining case for austerity?

Different people make different cases for austerity. Mike Shedlock someone who acknowledges everything posted in the OP has his, others have theirs. In the article linked Shedlock argues against those using the Money Multiplier Theory in their analysis. He also acknowledges the strong case made by Steve Keen that lending come first, reserves later.

The BIS paper from 2009 linked to by Shedlock also discusses a lot of this already.p13. The transmission mechanism of balance sheet policy

p13. Main channels

p14. Differing emphasis on the transmission mechanism

p16. Are bank reserves special?

p18. Bank reserves, bank lending, money and inflation

p19. Does financing with bank reserves add power to balance sheet policy?

p21. Is financing with bank reserves uniquely inflationary?0 -

Ah, I think I see articles of his posted every now and then on the Naked Capitalism daily links, and I think he and Steve Keen are friends (or at least acquainted); I can't immediately find a good link on his pro-austerity views, but (even though I'm not that knowledgeable of his blog) he does seem to be a good writer.Different people make different cases for austerity. Mike Shedlock someone who acknowledges everything posted in the OP has his, others have theirs. In the article linked Shedlock argues against those using the Money Multiplier Theory in their analysis. He also acknowledges the strong case made by Steve Keen that lending come first, reserves later.

The BIS paper from 2009 linked to by Shedlock also discusses a lot of this already.

Yes, I think that Austrian's in general - even though many still seem to hold onto fractional-reserve views - certainly are far more likely to recognize the true nature of credit/money creation, than mainstream/neoclassical/neoliberal economists; many economists, of all varieties, have had similar views going back at least 80 years I think - but it's been kept a fringe view for a long time.

None of this knowledge is new, but the BoE's statement should now make these views a lot more influential and mainstream, finally and definitively correcting the misinformation about fractional reserve banking and the money multiplier etc., which has dominated macroeconomic teaching for an extremely long time now.0 -

KyussBishop wrote: »Ah, I think I see articles of his posted every now and then on the Naked Capitalism daily links, and I think he and Steve Keen are friends (or at least acquainted); I can't immediately find a good link on his pro-austerity views, but (even though I'm not that knowledgeable of his blog) he does seem to be a good writer.

If you search Keen's blog or Mish's, you can find some friendly/civil back and forth debating between the two and you'll see some of his arguments.Yes, I think that Austrian's in general - even though many still seem to hold onto fractional-reserve views - certainly are far more likely to recognize the true nature of credit/money creation, than mainstream/neoclassical/neoliberal economists; many economists, of all varieties, have had similar views going back at least 80 years I think - but it's been kept a fringe view for a long time.

In common with Keen they criticize mainstream economic models. But their criticism is part of a more general attack on economic models for making too many aggregations and simplifications. In regards to money creation, some get it wrong, some more wrong than others.0 -

Interesting - I'll search that out.If you search Keen's blog or Mish's, you can find some friendly/civil back and forth debating between the two and you'll see some of his arguments.

In common with Keen they criticize mainstream economic models. But their criticism is part of a more general attack on economic models for making too many aggregations and simplifications. In regards to money creation, some get it wrong, some more wrong than others.

Yes, as Keen writes often, most mainstream economic models leave out all of banks, debt and money - hard to make any kind of a relevant model with that!

I'm pretty enthusiastic about Keen's approach to dynamic modelling, that he is doing with his Minsky program now - that, to me, seems to be a good platform for testing to see how the dynamics of different economic models/theories, hold out in reality (there's a lot of debate about how useful economic modelling can possibly be at all, but to be honest I don't understand that debate so well - it's very convoluted and mired in philosophical discussion, and kind of just comes off as trying to excuse economic theories, from being held to account when they don't describe reality accurately).0 -

Keen can be applauded for including banks, debt and money in his models. His model makes some good assumptions, has algorithms and outputs results that match loosely(16.05) what has happened in terms of debt, inflation and unemployment. Its neat. But it still makes simplifications and misses insights that could be gained without the aggregation.

Keen's view of cycles actually has a lot in common with Austrian Business Cycle Theory. One big difference is Keen's model does not attempt to look at shifts of labour and capital from industry to industry, his model treats labour as a homogenous blob. Roger Garrison gives a more "formalized" exposition of ABCT and how it models this.0 -

Ya I think something Keen said was ABCT is a good theory for modelling the run-up to a crisis, and debt-deflation a good theory for modelling what happens after a crisis hits.Keen can be applauded for including banks, debt and money in his models. His model makes some good assumptions, has algorithms and outputs results that match loosely(16.05) what has happened in terms of debt, inflation and unemployment. Its neat. But it still makes simplifications and misses insights that could be gained without the aggregation.

Keen's view of cycles actually has a lot in common with Austrian Business Cycle Theory. One big difference is Keen's model does not attempt to look at shifts of labour and capital from industry to industry, his model treats labour as a homogenous blob. Roger Garrison gives a more "formalized" exposition of ABCT and how it models this.

True, right now his models only cover 1 or 2 sectors, due to the limitations of the modelling program he is using - so indeed, there are a lot of simplifications there, missing out insights.

He is planning though, to expand his Minsky modelling program to include multiple sectors, and eventually all sectors in an economy (and then after that, do this with other economies and then model international interaction between multiple-sector economies), and he is also going to look to setup a massive centralized database of agglomerated economic data (with the new 'Institute for Dynamic Economic Analysis'), to assist in modelling economies - updated in realtime, eventually.

However, even though that would be able to (I assume) model the flow of labour between sectors, it would still likely not take into account things like skillsets of workers and how that may affect labour flow - which is a good point.0 -

KyussBishop wrote: »However, even though that would be able to (I assume) model the flow of labour between sectors, it would still likely not take into account things like skillsets of workers and how that may affect labour flow - which is a good point.

I think ABCT captures some aspects of business cycles that are completely ignored by other theories, a lot of attention is paid to resource misallocation and malinvestment, that said there is a lot of room for improvement. The thing that I like about Keen's view of cycles is that it could explain longer currency life-cycles, from birth to death, where the economy goes through a few business cycles until debt levels become too large and the last cycle finishes off the currency, at least in its current shape and form.0 -

Here is an article on this by Paul Ferguson - first one I've noticed in an Irish newspaper - who runs the Irish Sensible Money campaign (which has much in common with the UK Positive Money campaign):

http://www.independent.ie/business/personal-finance/banks-dont-work-the-way-you-think-but-they-should-30150400.html

Paul actually gives an extremely good description of the basic problems with mainstream (neoclassical) economics, with the current system of banking, and a brief overview of the history of this - so worth a quick read.

I don't necessarily agree with his proscriptions though, as his preferred ideas of monetary reform are different to what I normally advocate - but nonetheless they're still quite close to my own views.0 -

Advertisement

-

KyussBishop wrote: »Here is an article on this by Paul Ferguson - first one I've noticed in an Irish newspaper - who runs the Irish Sensible Money campaign (which has much in common with the UK Positive Money campaign):

http://www.independent.ie/business/personal-finance/banks-dont-work-the-way-you-think-but-they-should-30150400.html

Paul actually gives an extremely good description of the basic problems with mainstream (neoclassical) economics, with the current system of banking, and a brief overview of the history of this - so worth a quick read.

I don't necessarily agree with his proscriptions though, as his preferred ideas of monetary reform are different to what I normally advocate - but nonetheless they're still quite close to my own views.

offtopic here but Kyuss rocks. way better than qotsa!!0 -

Apparently Friedman made the same argument, that governments don't need to borrow money into existence.

http://econintersect.com/b2evolution/blog2.php/2014/02/26/u-s-government-is-a-user-should-be-an-issuer-of-money0 -

Yea kind of picked this name, out of a random part of other names I'd been using elsewhere, and what I was listening to at the time; most of Josh-Homme-related music is very goodthrashmetalfan wrote: »offtopic here but Kyuss rocks. way better than qotsa!! 0

0 -

Ya Friedman was very unusual in his economic views - definitely an outlier (particularly given his history/background, and the type of economics he helped develop), in his support of government use of money creation; though his monetarist policies/ideas failed quite badly.Apparently Friedman made the same argument, that governments don't need to borrow money into existence.

http://econintersect.com/b2evolution/blog2.php/2014/02/26/u-s-government-is-a-user-should-be-an-issuer-of-money

That article makes a good point, that MMT doesn't necessarily describe the current system in place - I made that mistake at the start of the MMT thread on this forum, taking as true that government creates/destroys money, when this is absolutely not true for the EU; I do however, think this is true for the US (the treasury, if I recall correctly, issues the money first and then is legally obliged to match it with bond issuance afterwards).

However, the actual accounting/mechanics surrounding that is, I believe, meant to be quite complicated - so I put off forming a concrete opinion on all of that for now; I'd need to read up on it more specifically.0 -

That author in the linked article, Derryl Hermanutz, really knows his stuff - searching out writing/comments from him, on sites I read regularly on economics stuff, and he has put out marathon comments like this one, which cut across and link-up, a whole ton of topics from the functioning of the monetary system, government spending through the monetary system, bank fraud, mechanics of getting away with fraud, right down to neoliberalism/austerity and how this is used to destroy countries in banks/finances favour:

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/01/sovereign-spending-and-public-goods.html#comment-94776

He seems to know the topic inside-out, and is a very good writer, from the little I have seen.0 -

Martin Wolf - the person I used to cite to back the point "banks create money when they make loans", before the BoE report - has put out a good article just there: "Only the ignorant live in fear of hyperinflation"

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/46a1ce84-bf2a-11e3-a4af-00144feabdc0.html

Some snippets - these ones don't really add anything beyond what has already been said thus far in the thread though, other than some small interesting insights:Martin Wolf wrote:The act of saving does not increase deposits in banks. If your employer pays you, the deposit merely shifts from its account to yours.

...

What makes banks special is that their liabilities are money – a universally acceptable IOU. In the UK, 97 per cent of broad money consists of bank deposits mostly created by such bank lending. Banks really do “print” money. But when customers repay, it is torn up.

...

the “money multiplier” linking lending to bank reserves is a myth. In the past when bank notes could be freely exchanged for gold, that relationship might have been close. Strict reserve ratios could yet re-establish it. But that is not how banking operates today. In a fiat (or government-made) monetary system, the central bank creates reserves at will.

...

the authorities can also affect the lending decisions of banks by regulatory means – capital requirements, liquidity requirements, funding rules and so forth. The justification for such regulation is that bank lending creates spillovers or “externalities”. Thus, if many banks lend against the same activity – property purchase, for example – they will raise demand, prices and activity, so justifying yet more lending. Such a cycle might lead – indeed often has led – to a market crash, a financial crisis and a deep recession. The justification for systemic regulation is that it will, or at least should, attenuate these risks.

...

This is not just academic. Understanding the monetary system is essential. One reason is that it would eliminate unjustified fears of hyperinflation. That might occur if the central bank created too much money. But in recent years the growth of money held by the public has been too slow not too fast. In the absence of a money multiplier, there is no reason for this to change.

However, his last paragraph seems to me, to be a pretty ginormous (and very publicly important) change of view, for someone as influential as Martin Wolf (since he is the editor of the Financial Times):Martin Wolf wrote:A still stronger reason is that subcontracting the job of creating money to private profit-seeking businesses is not the only possible monetary system. It may not be even the best one. Indeed, there is a case for letting the state create money directly. I plan to address such possibilities in a future column.0 -

Very interesting thread, thanks for keeping it updated Kyuss0

-

KyussBishop wrote: »That author in the linked article, Derryl Hermanutz, really knows his stuff - searching out writing/comments from him, on sites I read regularly on economics stuff, and he has put out marathon comments like this one, which cut across and link-up, a whole ton of topics from the functioning of the monetary system, government spending through the monetary system, bank fraud, mechanics of getting away with fraud, right down to neoliberalism/austerity and how this is used to destroy countries in banks/finances favour:

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/01/sovereign-spending-and-public-goods.html#comment-94776

He seems to know the topic inside-out, and is a very good writer, from the little I have seen.

In case anyone reading this thread hasn't, the comments from Derryl Hermanutz are well worth a read.0 -

Originally Posted by Martin Wolf

This is not just academic. Understanding the monetary system is essential. One reason is that it would eliminate unjustified fears of hyperinflation. That might occur if the central bank created too much money. But in recent years the growth of money held by the public has been too slow not too fast. In the absence of a money multiplier, there is no reason for this to change.

If he is talking about a fear of hyperinflation via the money multiplier he is correct in saying it is unjustified. However that is not the argument most make for hyperinflation. The bolded part is a little closer to their argument.

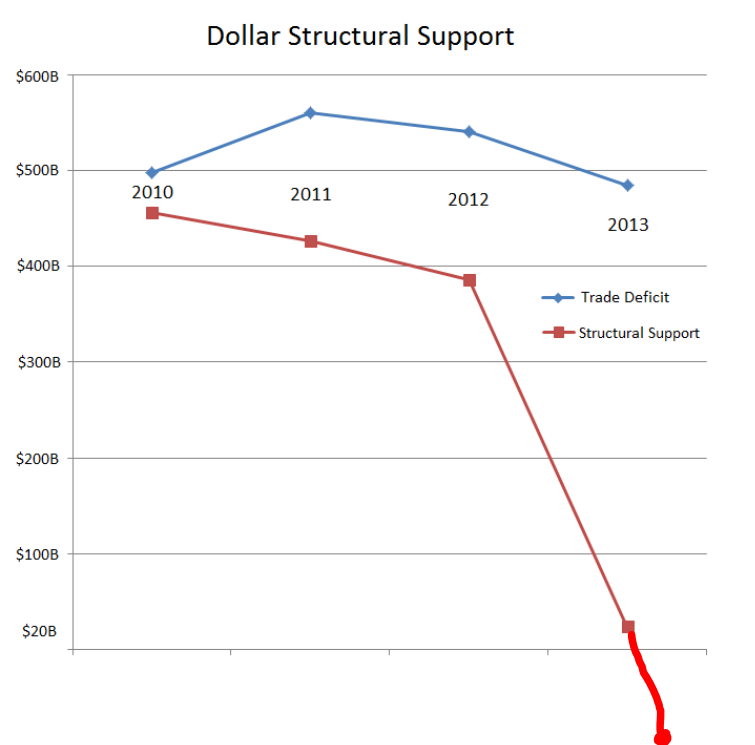

To keep it some way simple the argument for dollar hyperinflation is that it will come from a wane in foreign support for US debt and the USD as reserve, along with an unwillingness to reign in deficit spending, leading to a feedback loop. If the US budget deficit is larger than the trade deficit, even if all the dollars going abroad as a result of the trade deficit were used to buy government debt, the FED would have to buy the difference and add to the dollar money supply. If foreign dollar holders walk away from buying US government debt the number of new dollars the FED needs to create dramatically increases.

Structural support in the graph below is the increase in US debt held by foreign CB's. There has actually been a decrease in the amount of government debt held by foriegn CB's in the past year. 0

0 -

Advertisement

-

The US certainly has a large advantage through being the reserve currency, and if that ever changes then they are certainly going to go through an upheaval and have to start actually producing goods for export in increasing numbers, to arrest a fall in value of the US dollar - all of that's going to happen someday alright, though is separate to the problem of deficit spending using money creation.If he is talking about a fear of hyperinflation via the money multiplier he is correct in saying it is unjustified. However that is not the argument most make for hyperinflation. The bolded part is a little closer to their argument.

To keep it some way simple the argument for dollar hyperinflation is that it will come from a wane in foreign support for US debt and the USD as reserve, along with an unwillingness to reign in deficit spending, leading to a feedback loop. If the US budget deficit is larger than the trade deficit, even if all the dollars going abroad as a result of the trade deficit were used to buy government debt, the FED would have to buy the difference and add to the dollar money supply. If foreign dollar holders walk away from buying US government debt the number of new dollars the FED needs to create dramatically increases.

Structural support in the graph below is the increase in US debt held by foreign CB's. There has actually been a decrease in the amount of government debt held by foriegn CB's in the past year.

The thing about using money creation to fund government: You don't need any government debt public debt becomes obsolete, because it is no longer needed to fund government.

public debt becomes obsolete, because it is no longer needed to fund government.

Government debt is actually more inflationary than using money creation for fiscal spending, because it's an asset that is almost as good as money, and it carries interest, making it more inflationary (and more profitable/desirable to hold) than plain money

The currency valuation is purely a balance-of-trade issue in the end: Upon loss of reserve status, it's not government deficit spending that would be harming the value of the dollar, it would be choosing to run a trade deficit - and there are multiple ways to tackle that.

Reducing government spending and increasing taxes, closes a trade deficit by slowing down the economy so less is imported, and by undergoing 'internal devaluation' by putting negative pressure on wages - but that also means less is exported as well, and workers get even less of a share of the profits on goods/exports.

That's really inefficient: Instead, you want to decrease imports, and increase exports (if you can; or at least arrest any reduction in exports) - and if you have idle labour lying around (unemployment), then you're not making the most of your ability to produce/export goods - it's more rational then, to run a fiscal deficit, to keep full employment going (though that will only help indirectly, when it comes to exports - it's still more efficient though).0 -

Well I would agree and disagree with parts of that post. Something I am curious about is this:Government debt is actually more inflationary than using money creation for fiscal spending, because it's an asset that is almost as good as money, and it carries interest, making it more inflationary (and more profitable/desirable to hold) than plain money

If a government borrows and spends 100 billion it will affect prices the same as if it spent the 100 billion without it being borrowed. But, money is extinguished when the borrowed 100 billion is paid back. The money simply printed doesn't have this deflationary effect as it is not paid back and extinguished making it more inflationary.0 -

The thing to think about though: Debt grows faster than Money in an economy (because of interest payments), meaning the Debt:Money ratio is constantly increasing and Debt will become many multiples of Money over time (10x, 40x, 100x etc.), unless something is done to reduce the ratio of Debt:Money.Well I would agree and disagree with parts of that post. Something I am curious about is this:

If a government borrows and spends 100 billion it will affect prices the same as if it spent the 100 billion without it being borrowed. But, money is extinguished when the borrowed 100 billion is paid back. The money simply printed doesn't have this deflationary effect as it is not paid back and extinguished making it more inflationary.

That is done, by borrowing more money - creating more money (and debt) on a 1:1 ratio - which pulls the overall ratio of Debt:Money back down.

In the current monetary system, debts have to be rolled over, forever - debts (aggregate public and private debts) are not paid down, ever: Otherwise there would be no money in the economy at all

So, interest has to be paid on debt-based money - it's this interest that is inflationary, because that is what perpetuates the requirement, that Debt be rolled over with more Debt.

Here's a table in the context of US, which covers a lot of this (Platinum Coin Seigniorage = public money creation):

Originally from here: http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/12/platinum-coin-seigniorage-issuing-debt-keystroking-deficit-spending-and-inflation.html0 -

In the current monetary system, debts have to be rolled over, forever - debts (aggregate public and private debts) are not paid down, ever: Otherwise there would be no money in the economy at all.

Agree with that.So, interest has to be paid on debt-based money - it's this interest that is inflationary, because that is what perpetuates the requirement, that Debt be rolled over with more Debt.

Now I see what you are saying. That the current system has to inflate, that it is an inflationary system. And I think you are saying if we had a system that used debt free money creation the system wouldn't be required to inflate?

I would disagree with that chart though. Although it could be just their wording.0 -

I think it's still desirable to have some steady level of inflation anyway, for other reasons, but certainly - government money creation (debt-free money), certainly doesn't carry the inflationary pressure of interest-bearing government debt (debt-based money); you could have zero inflation (or target it at least), but I don't think it'd be desirable.Agree with that.

Now I see what you are saying. That the current system has to inflate, that it is an inflationary system. And I think you are saying if we had a system that used debt free money creation the system wouldn't be required to inflate?

I would disagree with that chart though. Although it could be just their wording.

So there would still be inflation, but it would no longer be a mandatory built-in condition of the economic/monetary system.

Government would have more control over inflation with money creation vs public debt: There would be no interest payments causing added inflationary pressure, no incentive to use inflation deliberately for reducing the debt load as a percentage of GDP, and no escalating inflationary pressures on increased government spending (e.g. from skyrocketing interest rates on debt).

Politicians and the population would also understand better (due to seeing that money would be directly created and removed from circulation by government), how inflation management really works and that taxes play a significant part in this - and so the political gain from excessively inflationary policies would be limited.

That graph confused me a lot for a while when I first saw it - this is the first time I've brought it up in ages, and (given the context of what I've learned since), makes a lot more sense to me now.0 -

Well, this couldn't be more explicit - Martin Wolf:

"Strip private banks of their power to create money"

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/7f000b18-ca44-11e3-bb92-00144feabdc0.html

Some more relevant parts:Martin Wolf wrote:...the central bank would create new money as needed to promote non-inflationary growth. Decisions on money creation would, as now, be taken by a committee independent of government.

Finally, the new money would be injected into the economy in four possible ways: to finance government spending, in place of taxes or borrowing; to make direct payments to citizens; to redeem outstanding debts, public or private; or to make new loans through banks or other intermediaries. All such mechanisms could (and should) be made as transparent as one might wish.

The transition to a system in which money creation is separated from financial intermediation would be feasible, albeit complex. But it would bring huge advantages. It would be possible to increase the money supply without encouraging people to borrow to the hilt. It would end “too big to fail” in banking. It would also transfer seignorage – the benefits from creating money – to the public. In 2013, for example, sterling M1 (transactions money) was 80 per cent of gross domestic product. If the central bank decided this could grow at 5 per cent a year, the government could run a fiscal deficit of 4 per cent of GDP without borrowing or taxing. The right might decide to cut taxes, the left to raise spending. The choice would be political, as it should be.

...

This will not happen now. But remember the possibility. When the next crisis comes – and it surely will – we need to be ready.

As described above, part of this can mean, government use of money creation, for fiscal funding - that pretty much vindicates MMT, and from an economist as influential as Martin Wolf no less (again: leading editor of the Financial Times).

This is a pretty big deal, in my view - hopefully should see support for this kick up a lot of steam now, since this is going to help it gain a lot more credibility.0 -

Advertisement

-

Great article, which explains what the BoE's report means for Quantitative Easing (also touching on what it means for interest rates) - why (sustained) QE is not as helpful as it is made out to be, and may be a net-harm:

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101649411Paul Gambles wrote:...

In the BoE's latest quarterly bulletin, they conceded this point, recognizing that QE is indeed tantamount to pushing on a piece of string. The article tries to salvage some central banker dignity by claiming somewhat hopefully that the artificially lower interest rates caused by QE might have stimulated some loan demand.

However the elasticity or price sensitivity of demand for credit has long been understood to vary at different points in the economic cycle or, as Minsky recognized, people and businesses are not inclined to borrow money during a downturn purely because it is made cheaper to do so. Consumers also need a feeling of job security and confidence in the economy before taking on additional borrowing commitments.

It may even be that QE has actually had a negative effect on employment, recovery and economic activity.

This is because the only notable effect QE is having is to raise asset prices. If the so-called wealth effect -- of higher stock indices and property markets combined with lower interest rates -- has failed to generate a sustained rebound in demand for private borrowing, then the higher asset values can start to depress economic activity. Just think of a property market where unclear job or income prospects make consumers nervous about borrowing but house prices keep going up. The higher prices may act as either a deterrent or a bar to market entry, such as when first time buyers are unable to afford to step onto the property ladder.

Dr Andrea Terzi, Professor of Economics at Franklin University Switzerland, also suggests that many in the banking and finance industry, who often have trouble with the way academics teach and discuss monetary policy, will find the new view much closer to their operational experience. "The few economists who have long rejected the 'state-of-the-art' in their models, and refused to teach it in their classrooms, will feel vindicated," he adds.

Foremost among those economists is Prof Steve Keen: a long-time proponent of the alternative view, endogenous money. Having co-presented with Prof. Keen, I've been taken with the way that his endogenous money beliefs stand up to 'the common sense test.' The proverbial 'man on the Clapham omnibus' knows that borrowing your way out of debt while your returns are dwindling makes no sense. Friedman and Bernanke couldn't see that.

Ben Bernanke positioned himself as a student of history who had learned from the mistakes of the past. Dr. Terzi questions this, "This view that interest rates trigger an effective 'transmission mechanism' is one of the Great Faults in monetary management committed during the Great Recession."

"The reality is that the level of interest rates affects the economy mildly and in an ambiguous way. To state that monetary policy is powerful is an unsubstantiated claim."

For a central bank to recognize that its economic understanding is flawed is a major admission. However, unless it takes the opportunity to correct its policy in line with this new understanding then it will repeat the same old mistakes.

The world's central banks are steering a course unwittingly directly towards a repeat of the 1930s but on a far greater scale. It's not yet clear that there is any commitment to change this course or indeed whether there is still time to do so. Either way, it will be very interesting to see what future economic historians make of Ben Bernanke's contribution to economic policy.

Nice hat-tip to Steve Keen there as well.0 -

The UK Parliament is going to have a 3 hour debate on money creation (for the first time in 170 years), on the 20th of November:

http://www.positivemoney.org/2014/11/uk-parliament-debate-money-creation-first-time-170-years/

This should be interesting - if there's any kind of a decent turnout.0 -

Here is the full transcript of the UK Parliament debate on money creation - it is an interesting debate:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/hansard/commons/todays-commons-debates/read/unknown/314/

I'm only part way through it, and while I'm impressed that Steve Baker initiated that debate, am less than impressed with some of his views about how the monetary system should be reformed (he seems to support virtually complete removal of government supervision/control over money creation - currently through the central bank - and replacement with unlimited privately-created alternative currencies; even backing the alternative currencies through allowing their use for taxation, which I view as very dangerous democratically) - still, it's a very interesting debate.0 -

Finally finished reading the whole debate - even though there is quite a lot I disagree with, and even though I'd have a different point of view to many in the debate, it was overall an extremely good debate which discusses issues in detail that you pretty much never hear talked about, outside of the topic of money creation.

It's a very long read unfortunately, but extremely good at parts.

Interestingly, there is also mention of the Irish version of 'Postive Money' (PM are an influential monetary reform group within the UK, who can probably be partially credited with this debate) - the Irish version is 'Sensible Money':

I think Sensible Money are now defunct though.Mark Durkan (Foyle) (SDLP):

People in organisations such as Positive Money in the UK or Sensible Money in Ireland are therefore saying, rightly, that politics—those of us charged with overseeing public policy as it affects the economy—need to have more of a basic look at how we treat the banking system and at the very nature of money creation.0 -

Calls for government spending, funded by money creation, are starting to become increasingly more mainstream now - slowly though - following in the footsteps of 'endogenous money' (i.e. the idea that banks create money when they make loans, and do not actually lend out deposits/savings):

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/nov/26/eu-cash-bomb-recession-juncker-new-fund

Martin Wolf in particular, the leading Financial Times editor, seems to be one of the leading voices pushing this into mainstream discussion. Given how quickly 'endogenous money' has achieved credibility, and how discussion of government spending from money creation is picking up steam in a similar way now, this could enormously and permanently transform public/media discussion of economic/political issues, extremely quickly.

A few years ago, the idea that banks don't lend from deposits/savings, but create money when they make loans, was viewed as ridicule-worthy, yet is now pretty much undeniable; the same kneejerk reaction is made whenever the idea of government use of created money comes up, yet here are some of the same people who led the way in bringing 'endogenous money' to mainstream legitimization, doing the same with government use of created money.

Once that achieves mainstream credibility, people are really going to be wondering "what in fúck have we been doing for the past 6-7 years?", as it makes world economic policy since the crisis, look insane.0 -

Advertisement

-

Economists have observed that banks create money on loan origination for at least over a century. Isn't the misconception that is now emphasized more to do with the fact that banks are not limited in the amount of money they create by the amount of reserves they have on hand as explained in textbooks?

I also don't see the focus on how money is created being ridiculed, more so the policy prescriptions of those focusing on money creation. Hasn't that been your own experience on these forums? I don't recall you being ridiculed for pointing out that banks create money when they make loans, but I do recall you being ridiculed for policy prescriptions.0 -

What I said was "the idea that banks don't lend from deposits/savings, but create money when they make loans" - only a minority of economists have observed that, and mainstream economic theory has been based upon 'loanable funds' (the idea that banks lend from deposits/savings, with a money multiplier), for a very long time.

On Boards overall, that idea has always generated a kneejerk backlash, until Martin Wolf and the Bank of England report, gave me enough ammo to legitimize it.

The same with government use of created money: One of the few posters I have encountered who is capable of actually discussing that, without a kneejerk backlash claiming hyperinflation, is yourself (and others specifically here on Economics); now Martin Wolf and others, are in the process of legitimizing that idea now too.